George was now thirteen, a crisis age, placed by circumstances at a crisis of events, and the advice he later gave a nephew might have fitted his situation now:

At this crisis your conduct will attract the notice of those who are about you [he wrote George Steptoe Washington in 1789] . . . . Your doings now may mark the leading traits of your character through life. It is absolutely necessary if you mean to make any figure upon the stage, that you should take the first steps right. . . . The first great object . . . is to acquire, by industry and application, such knowledge as your situation enables you to obtain.

At Wakefield, now a graceful country mansion presided over in casual elegance by the fashionable Anne Aylett, he put these precepts into practice, trailing Augustine like a small and watchful shadow, studying his motions as the models for his own. His horizons widened, he attacked his studies with new energies; a cousin recalled his unexpected industry and assiduity at school. “While his brother and the other boys were at playtime,” he remembered, George remained “behind the door, ciphering,” preternaturally serious, except for “one youthful ebullition . . . romping with one of the largest girls.” To guard against the threat of social error, he copied out in painful longhand 110 “Rules of Civility and Social Conduct,” blending general advice for deference to those of greater station with such specific precepts as “Wear not your cloths foul, unript or dusty,” and “In the Presence of Others Sing not to yourself with a Humming Noise, nor Drum with your Fingers or Feet.”

Doubtless, these stood him to advantage when he was transferred to Mount Vernon in the spring of 1745, a sizable advance on his previous experience and a promotion both in quality and kind. Ferry Farm had been a backwater, Wakefield a pleasant country mansion; Belvoir and Mount Vernon were working factors in the web of empire that swung from Bengal to the Alleghenies, with London as its hub. Already, that small circle was an axis of some power; William Fairfax had moved to the Council in 1742, his son George William taking his place in the House of Burgesses; in 1744 Frederick had been detached from Prince William County, and Lawrence, with the Fairfax influence behind him, slipped into the created seat. Lawrence, Anne, and now George Washington were at Belvoir often, mingling with the swarm of notables who frequented the mansion’s hall. . . .

Eclat, however, was only part of what Belvoir had to offer. Among the staples of its library was Cato by Joseph Addison (a London crony of Lord Fairfax), a post facto defense of the Bloodless Revolution that became the staple of the parliamentary party in both Britain and the colonies and the staple of their revolution when it broke. At Belvoir it was read often, performed frequently, taken with great reverence by all. George’s part in these performances was a minor miracle of casting; he played Juba, an adoptive son and protégé of Cato, who fell in love with Cato’s daughter, against his judgment and certainly against his will. (“I should think our time more agreeable spent, believe me,” George wrote Sally Cary Fairfax in 1755, “playing a part in Cato with the company you mention, and myself doubly happy in being the Juba to such a Marcia as you must make.”)

What did George take out of Cato, besides the memory of Sally Fairfax’s black eyes? Cato was an enemy of Julius Caesar, and his strictures against the rising empire cast the line of values by which the self-conscious classicists lived. George, always one to take instruction seriously, absorbed through this painless medium the idea that civility was to be prized above the state of nature:

A Roman soul is bent on higher views:

To civilize the rude, unpolish’d world,

And lay it under the restraint of laws;

To make man mild and sociable to man,

To cultivate the wild, licencious savage

With wisdom, discipline, and liberal arts,

The embellishment of life. Virtues like these

Make human nature shine, reform the soul,

And break our fierce barbarians into men.

reason over instinct:

Let not a torrent of impetuous zeal

Transport thee beyond the bounds of reason:

True fortitude is seen in great exploits

That justice warrants, and that wisdom guides;

All else is tow’ring frenzy and distraction.

justice over laxity of standards:

. . . this base, degenerate age requires

Severity, and justice in its rigour. . . .

This awes an impious, bold offending world

Commands obedience, and gives force to laws.

When by just vengeance guilty mortals perish

The Gods regard the punishment with pleasure

And lay the uplifted thunderbolt aside.

public service over private comfort:

. . . what pity is it

That we can die but once to serve our country. . . .

I should have blushed if Cato’s house had stood

Secure, and flourished in a civil war. . . .

My life is not my own when Rome demands it.

the great ideal of perseverance under pressure:

. . . valour soars above

What the world calls misfortune and affliction . . .

The Gods, in bounty, work up storms about us

That give mankind occasion to exert

Their hidden strength.

the enduring fear of arbitrary power:

Bid him disband his legions,

Restore the commonwealth to liberty,

Submit his actions to the public censure,

and stand the judgment of a Roman Senate,

Bid him do this, and Cato is his friend.

and, over all, the conviction that life without self-determination is worse than no life at all:

. . . let us draw her term of freedom out. . . .

A day, an hour, of virtuous liberty

Is worth a whole eternity in bondage.

Here, distilled, is the credo of the Whig ascendancy, which echoes through his lifetime like a chime: honor, discipline, impartial justice, order, and relentless self-control. An austere doctrine, lifting values over human virtues, with solace for the fortune-stricken but no mercy for the weak. Seductive doctrine for an adolescent, high-minded and unfanciful, conscious of emerging powers, seeking a channel in which they could be at once released and controlled. In their own right, these ideas would have made an impression; backed and sponsored by the men he loved and looked up to, they took a luster that would never fade. Washington would follow them, with the single-minded zeal of a religious postulant, from the first days of his awkward cubhood to his apogee as nationmaker and as head of state. For also in Cato, less noticed, in the beginning, but more telling for the end: “My life is grafted on the fate of Rome.”

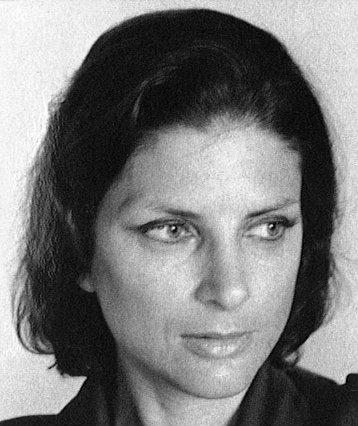

Noemie Emery. “Young Washington and Cato.” From Washington: A Biography. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1976, 42–47. Copyright © 1976 by Noemie Emery. Used by permission of the author.

Return to The Meaning of George Washington's Birthday.

Post a Comment