Introduction

Americans today take for granted that military and political leaders voluntarily surrender the powers of office and return to private life. But in the 18th and 19th century-world of hereditary monarchs and men on horseback (e.g., Napoleon), such practices were exceedingly rare. One anecdote vividly makes the point. England’s King George III once asked the painter Benjamin West, who was painting his portrait, “What do you think Washington will do after the war?” West replied, “Well, Your Majesty, I believe he will return to his farm.” And the King said, “If he does that, then he is the greatest man in the world.”

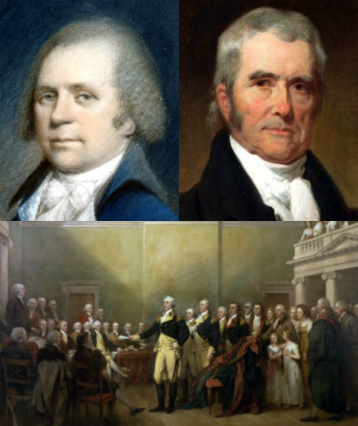

The two letters comprising this selection present contemporaneous American reactions to Washington’s resignation of his commission. The Irish-born early American statesman James McHenry (1753–1816), delegate to the Continental Congress from Maryland, then a signer of the United States Constitution, and, later, Secretary of War under Presidents Washington and John Adams, was present on the occasion. In this letter from Annapolis to his fiancée Margaret Caldwell, dated December 23, 1783 (the same day as the resignation), McHenry describes the actual scene. Two weeks later, on January 3, 1784, John Marshall (1755–1835), whose 35-year tenure as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court would effectively establish the Court as an equal branch of the federal government, wrote this brief note to James Monroe (1758–1831), the future fifth president of the United States.

What do these letters add to your appreciation of the event, and of Washington’s state of mind and heart on the occasion? What do they add to your understanding of the relation of Washington to his fellow American patriots? Can you square his modesty with their exalted view of him?

James McHenry, Letter to his fiancée Margaret Caldwell

Annapolis, December 23, 1783

Today my love the General at a public audience made a deposit of his commission and in a very pathetic [i.e., emotional] manner took leave of Congress. It was a Solemn and affecting spectacle; such an one as history does not present. The spectators all wept, and there was hardly a member of Congress who did not drop tears. The General’s hand which held the address shook as he read it. When he spoke of the officers who had composed his family, and recommended those who had continued in it to the present moment to the favorable notice of Congress he was obliged to support the paper with both hands. But when he commended the interests of his dearest country to almighty God, and those who had the superintendence of them to his holy keeping, his voice faltered and sunk, and the whole house felt his agitations. After the pause which was necessary for him to recover himself, he proceeded to say in the most penetrating manner, “Having now finished the work assigned me I retire from the great theater of action, and bidding an affectionate farewell to this august body under whose orders I have so long acted I here offer my commission and take my leave of all the employments of public life.” So saying he drew out from his bosom his commission and delivered it up to the president of Congress. He then returned to his station, when the president read the reply that had been prepared—but I thought without any showing of feeling, though with much dignity.

This is only a sketch of the scene. But, were I to write you a long letter I could not convey to you the whole. So many circumstances crowded into view and gave rise to so many affecting emotions. The events of the revolution just accomplished—the new situation into which it had thrown the affairs of the world—the great man who had borne so conspicuous a figure in it, in the act of relinquishing all public employments to return to private life—the past—the present—the future—the manner—the occasion—all conspired to render it a spectacle inexpressibly solemn and affecting.

* * *

John Marshall, Letter to James Monroe

Richmond, January 3, 1784

At length then the military career of the greatest Man on earth is closed. May happiness attend him wherever he goes. May he long enjoy those blessings he has secured to his Country. When I speak or think of that superior Man my full heart overflows with gratitude. May he ever experience from his Countrymen those attentions which such sentiments of themselves produce.

Return to The Meaning of George Washington's Birthday.

Post a Comment