Introduction

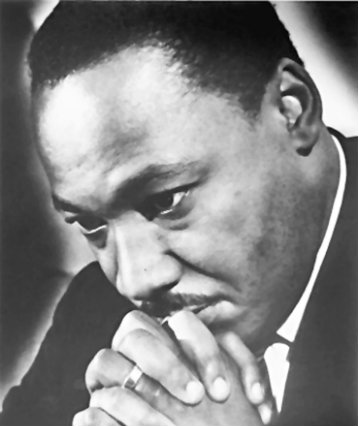

King wrote this letter on April 16, 1963, in response to “A Call for Unity,” a letter that had been published three days earlier by eight politically moderate white clergymen opposing the tactics of direct action and civil disobedience. King’s incarceration caused local and national consternation, and his release was effected on April 20th by the intervention of President John F. Kennedy. His letter from jail, written on scraps of newspaper and handed out in bits and pieces to his supporters who assembled them into a coherent and eloquent argument, was published in several magazines in May and June, and did a great deal to enhance King’s reputation and national following. (Recall that the March on Washington took place that same year, in late August.)

Going carefully through the letter, topic by topic, present and evaluate King’s response to the clergymen. Which arguments, in each case, do you find most—and which least—persuasive or moving? Consider in addition these questions, pertinent to the tactics of direct action and (especially) civil disobedience: Is King right, in answering the charge that he is an outsider, that injustice in any community in the United States is everyone’s proper business, or might there be reasons, in our federal republic, for allowing local communities to sort out their own affairs? King says that the purpose of his nonviolent direct action program “is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.” What are the benefits and risks of such an approach to seeking political change? In offering his eloquent defense of civil disobedience,* King justifies his willingness to break laws by claiming that one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws, those that are out of harmony with “the moral law or the law of God.” Can we citizens of a pluralistic society know with certainty—and agree—on the content of the moral law or the law of God? Although King accepts the charge that he is “an extremist”—like Jesus and Amos and Martin Luther—he also presents himself as a moderate, and as the only alternative between do-nothing complacency and separatist, violent black nationalism. How can he be both extremist and moderate? What do you make of King’s views about the proper role of the churches in the struggle for civil rights, and how do they fit with the American principles regarding the separation of church and state?

(2 votes, average: 4.50 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 4.50 out of 5)

Post a Comment