A New York Times series on the growing class divide in the nation found that an increasing percentage of the most successful students today are the children of the upper middle class and the rich. “Whatever children inherit from their parents—habits, skills, genes, contacts, money—seems to matter more today,” and family structure becomes a class issue in modern America, too, according to the Times. The best-educated Americans now have fewer children. They also give birth to those children later in life, when they have more money to spend on the children. This is true for white parents, black parents, and immigrant parents. The gap between money earned by people who graduated from college and money earned by those who did not doubled in the last twenty years. It is becoming harder for poor people to compete.

The good news is that there is a formula for getting out of poverty today. The magical steps begin with finishing high school, but finishing college is much better. Step number two is taking a job and holding it. Step number three is marrying after finishing school and while you have a job. And the final step to give yourself the best chance to avoid poverty is to have children only after you are twenty-one and married. This formula applies to black people and white people alike.

The poverty rate for any black man or woman who follows that formula is 6.4 percent. The overall poverty rate for black Americans, based on 2002 census data, the year this analysis was done, was 21.5 percent. In other words, by meeting those basic requirements, black Americans can cut their chances of being poor by two-thirds. This is a consistent pattern. By 2004 the poverty rate for any black man or woman who follows that formula is only 5.8 percent. That compares to an overall poverty rate of 24.7 percent for black people in 2004. Another way to look at it is that a black family that does not meet the requirements will more than triple their chances of being poor. Even white American families have a higher poverty rate (7.8 percent) than black people who finished high school, got married, had children after 21, and worked for at least one week a year. . . .

A 2002 report from the Institute for American Values, a nonpartisan group that studies families, concluded that “marriage is an issue of paramount importance if we wish to help the most vulnerable members of our society: the poor, minorities, and children.” The statistical evidence for that claim is strong. Research shows that in 2002 most black children, 68 percent, were born to unwed mothers. Those numbers have real consequences. For example, 35 percent of black women who had a child out of wedlock live in poverty. Only 17 percent of married black women overall are in poverty. In a 2005 report the institute concluded, “Economically, marriage for black Americans is a wealth-creating and poverty-reducing institution. The marital status of African American parents is one of the most powerful determinants of the economic status of African American families. . . .”

The authors noted that over the last fifty years, basically the period after the Brown decision, “the percentage of black families headed by married couples declined from 78 percent to 34 percent.” In the thirty years from 1950 to 1980, households headed by black women who never married jumped from 3.8 per thousand to 69.7 per thousand. That, too, had real consequences. In 1940, 75 percent of black children lived with both parents. By 1990 only 33 percent of black children lived with a mom and dad—“largely a result of marked increases in the number of never-married black mothers.” And there is no question about the impact on black children. With both parents in the house, they do better in school; the children of married people also have fewer run-ins with the police, as well as better self-esteem, and are more likely to enter into marriage before having children. This is a cycle of success creating more success and prosperity.

“For policymakers who care about black America, marriage matters,” wrote the authors of the report, a group of black scholars. They called marriage in black America an important strategy for “improving the well-being of African Americans and for strengthening civil society.”

Here is [Bill] Cosby at an October 2004 town-hall meeting in Milwaukee: “It is not all right for your fifteen-year-old daughter to have a child,” he told black parents. “I’m not talking to you any different from a grandfather who would say, ‘I wouldn’t do that if I were you.’”

A few days after his controversial speech in May 2004, Cosby wrote in the Los Angeles Times that “we don’t need another federal commission to study the problem [of black poverty]. Scholars such a W. E. B. Du Bois and John Hope Franklin . . . have already written eloquently on the subject. What we need now is parents sitting down with children, overseeing homework, sending children off to school in the morning well fed, clothed, and ready to learn.”

None of this is a matter of arguing over morality, blaming the poor, or excusing “the system” and its racism. Instead, Cosby and the academics are telling poor black people about sure-fire strategies for helping themselves and their families. There is no argument about the facts. If any person, including a black child born in poverty, will go as far as possible in school and show a willingness to work, he will be rewarded with enough money in his pocket to make it almost certain he will never get caught in poverty. If he also builds on the foundation of a strong marriage before having children, he will be rewarded: He will have even more money in his pocket, children who aspire to do well in school, and greatly reduced likelihood of seeing his children in trouble with drugs or having a run-in with the police that leads to jail. . . .

That is why it is important for someone of Bill Cosby’s stature to take a risk to get the message out about the road to economic salvation—education, families, and good parenting. That is why it is more than fair for Cosby to proclaim for all the world to hear that poor black people whose children are dropping out of high school, whose daughters are having babies out of wedlock, whose sons are filling up the jails, are not taking advantage of the doors that have opened since the Brown decision. When it comes to creating the good life themselves, too many of the poor are acting against their own best interests—they are hurting themselves and the black community.

Why? Again, the heart of the answer is that the poor are not getting important information from civil rights leaders, from politicians, and from their culture (their music, their movies, their fashion). There is no trusted source with a pulpit or a microphone telling people in need about the path to a better life. There is no one calling this situation a crisis. That is why it was so exceptional for Cosby to raise his voice and say to poor black people “we didn’t come from giving up . . . we came from surviving!”

The nation’s leading civil rights groups are missing in action in this effort to get out the good news. They claim to be too busy to get the message out. They are locked into arguing that “the system” is causing the continued high level of poverty in black America. Their goal seems to be to get government money for programs, grants, and scholarships for the black community. That money has done some good. But at this point a blind pursuit of government money to help the poor is a tried, failed strategy. It encourages patterns of dependency among black people. It leads to cynicism about what has become of the civil rights movement. In its finest hour the movement appealed to the conscience of the nation, to its ideals, by seeking justice. Now the movement has descended to using racial guilt trips, basically to extort government money for bigger budgets for programs that show no sign of working. The disdain for this shadow of a formerly great movement is so deep that many Americans, including Cosby, identity these black leaders with their hands out on behalf of the poor as “poverty pimps.”

There is no discounting the damage done by slavery and racism. They are a tragically heavy weight of history on black people. And while much of the burden has lifted, it can still be found weighing on black people, through stereotypes and negative images, leaving us at a real disadvantage. But with the Brown decision and the passage of civil rights and voting rights laws, the historic damage done by slavery and racism is no longer heavy enough to stop most black people from fighting through the static and making their way to a better life.

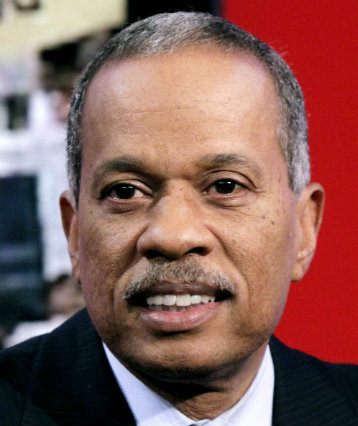

Williams, Juan. Enough. New York: Crown, 2006, 214–23. Copyright © 2006 by Juan Williams. Used by permission of the author.

Return to The Meaning of Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Post a Comment