Introduction

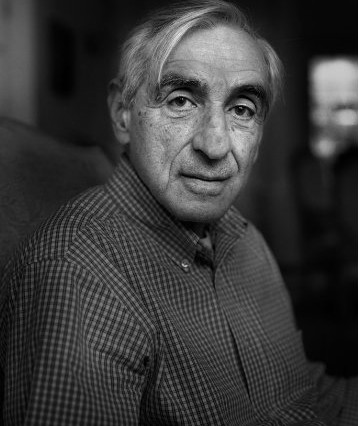

In this selection from Spheres of Justice: A Defense of Pluralism and Equality (1983), Michael Walzer (b. 1935) considers the prominent role that vacations now play in modern work life and how they differ from public holidays. A noted public intellectual and author, Walzer has written 27 books, including Just and Unjust Wars (1977), On Toleration (1997), and Arguing About War (2004). He currently serves as professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.

What, according to this selection, is the difference between a vacation and a holiday? Is having an extra day off or a three-day weekend vacation a fitting way to celebrate the worth and dignity of work and the American worker? Why or why not?

In the year 1960, an average of a million and a half Americans, 2.4 percent of the workforce, were on vacation every day. It is an extraordinary figure, and undoubtedly it had at that point never been higher. Vacations have indeed a short history—for ordinary men and women, very short: as late as the 1920s, Sebastian de Grazia reports, only a small number of wage earners could boast of paid vacations. The arrangement is far more common today, a central feature of every union contract; and the practice of “going away”—if not for many weeks, at least for a week or two—has also begun to spread across class lines. In fact, vacations have become the norm, so that we are encouraged to think of weekends as short vacations and of the years after retirement as a very long one. And yet the idea is new. The use of the word vacation to mean a private holiday dates only from the 1870s; the verb to vacation, from the late 1890s. . . .

What is crucial about the vacation is its individualist (or familial) character, greatly enhanced, obviously, by the arrival of the automobile. Everyone plans his own vacation, goes where he wants to go, does what he wants to do. In fact, of course, vacation behavior is highly patterned (by social class especially), and the escape it represents is generally from one set of routines to another. But the experience is clearly one of freedom: a break from work, travel to some place new and different, the possibility of pleasure and excitement. It is indeed a problem that people vacation in crowds—and, increasingly, as the size of the crowds grows, it is a distributive problem, where space rather than time is the good in short supply. But we will misunderstand the value of vacations if we fail to stress that they are individually chosen and individually designed. No two vacations are quite alike. . . .

It isn’t the only form of leisure; it was literally unknown throughout most of human history, and the major alternative form survives even in the United States today. This is the public holiday. When ancient Romans or medieval Christians or Chinese peasants took time off from work, it was not to go away by themselves or with their families but to participate in communal celebrations. A third of their year, sometimes more, was taken up with civil commemorations, religious festivals, saint’s days, and so on. These were their holidays, in origin, holy days, and they stand to our vacations as public health to individual treatment or mass transit to the private car. They were provided for everyone, in the same form, at the same time, and they were enjoyed together. We still have holidays of this sort, though they are in radical decline; and in thinking about them it will be well to focus on one of the most important of the survivals. [Professor Walzer here proceeds to consider the Sabbath, a communal holiday.]

Walzer, Michael. “Free Time.” From Spheres of Justice. New York: Basic Books, 1983. Copyright © by Michael Walzer. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Return to The Meaning of Labor Day.

Post a Comment