Introduction

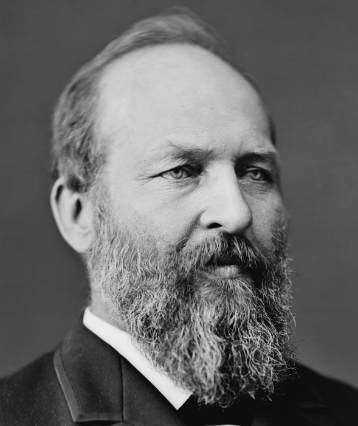

On May 30, 1868, a crowd of 5,000 gathered at Arlington National Cemetery for the first Decoration Day exercises. Before strewing flowers upon the graves of the dead, the crowd listened to an address by James A. Garfield (1831–81), then an Ohio congressman who had also served as a major general in the Civil War. In this first of such annual addresses at Arlington National Cemetery, Garfield, who in 1881 would become the 20th president of the United States, sets a standard by explaining what Decoration Day is all about and why it should be commemorated.

Garfield begins by asserting the poverty of speech in comparison to the deeds of the fallen. How does he ask us to regard the dead? And why should we the living envy them their lives and their deaths? What, according to Garfield, motivated the men to “condense life into an hour” and “joyfully welcom[e] death”? What does he mean by invoking the “unconscious influence” of past heroic sacrifices? How can “this silent assembly of the dead” become “voices [that] will forever fill the land like holy benedictions”? Why is Arlington National Cemetery a fitting resting place for these dead?

I am oppressed with a sense of the impropriety of uttering words on this occasion. If silence is ever golden, it must be here beside the graves of fifteen thousand men, whose lives were more significant than speech, and whose death was a poem, the music of which can never be sung. With words we make promises, plight faith, praise virtue. Promises may not be kept; plighted faith may be broken; and vaunted virtue be only the cunning mask of vice. We do not know one promise these men made, one pledge they gave, one word they spoke; but we do know they summed up and perfected, by one supreme act, the highest virtues of men and citizens. For love of country they accepted death, and thus resolved all doubts, and made immortal their patriotism and their virtue. For the noblest man that lives, there still remains a conflict. He must still withstand the assaults of time and fortune, must still be assailed with temptations, before which lofty natures have fallen; but with these the conflict ended, the victory was won, when death stamped on them the great seal of heroic character, and closed a record which years can never blot.

I know of nothing more appropriate on this occasion than to inquire what brought these men here; what high motive led them to condense life into an hour, and to crown that hour by joyfully welcoming death? Let us consider.

Eight years ago this was the most unwarlike nation of the earth. For nearly fifty years1 no spot in any of these states had been the scene of battle. Thirty millions of people had an army of less than ten thousand men. The faith of our people in the stability and permanence of their institutions was like their faith in the eternal course of nature. Peace, liberty, and personal security were blessings as common and universal as sunshine and showers and fruitful seasons; and all sprang from a single source, the old American principle that all owe due submission and obedience to the lawfully expressed will of the majority. This is not one of the doctrines of our political system—it is the system itself. It is our political firmament, in which all other truths are set, as stars in Heaven. It is the encasing air, the breath of the Nation’s life. Against this principle the whole weight of the rebellion was thrown. Its overthrow would have brought such ruin as might follow in the physical universe, if the power of gravitation were destroyed and

“Nature’s concord broke,

Among the constellations war were sprung,

Two planets, rushing from aspect malign

Of fiercest opposition, in mid-sky

Should combat, and their jarring spheres confound.”2

The Nation was summoned to arms by every high motive which can inspire men. Two centuries of freedom had made its people unfit for despotism. They must save their Government or miserably perish.

As a flash of lightning in a midnight tempest reveals the abysmal horrors of the sea, so did the flash of the first gun disclose the awful abyss into which rebellion was ready to plunge us. In a moment the fire was lighted in twenty million hearts. In a moment we were the most warlike Nation on the earth. In a moment we were not merely a people with an army—we were a people in arms. The Nation was in column—not all at the front, but all in the array.

I love to believe that no heroic sacrifice is ever lost; that the characters of men are molded and inspired by what their fathers have done; that treasured up in American souls are all the unconscious influences of the great deeds of the Anglo-Saxon race, from Agincourt to Bunker Hill. It was such an influence that led a young Greek, two thousand years ago, when musing on the battle of Marathon, to exclaim, “the trophies of Miltiades will not let me sleep!” Could these men be silent in 1861; these, whose ancestors had felt the inspiration of battle on every field where civilization had fought in the last thousand years? Read their answer in this green turf. Each for himself gathered up the cherished purposes of life—its aims and ambitions, its dearest affections—and flung all, with life itself, into the scale of battle.

And now consider this silent assembly of the dead. What does it represent? Nay, rather, what does it not represent? It is an epitome of the war. Here are sheaves reaped in the harvest of death, from every battlefield of Virginia. If each grave had a voice to tell us what its silent tenant last saw and heard on earth, we might stand, with uncovered heads, and hear the whole story of the war. We should hear that one perished when the first great drops of the crimson shower began to fall, when the darkness of that first disaster at Manassas fell like an eclipse on the Nation; that another died of disease while wearily waiting for winter to end; that this one fell on the field, in sight of the spires of Richmond, little dreaming that the flag must be carried through three more years of blood before it should be planted in that citadel of treason; and that one fell when the tide of war had swept us back till the roar of rebel guns shook the dome of yonder Capitol, and re-echoed in the chambers of the Executive Mansion. We should hear mingled voices from the Rappahannock, the Rapidan, the Chickahominy, and the James; solemn voices from the Wilderness, and triumphant shouts from the Shenandoah, from Petersburg, and the Five Forks, mingled with the wild acclaim of victory and the sweet chorus of returning peace. The voices of these dead will forever fill the land like holy benedictions.

What other spot so fitting for their last resting place as this under the shadow of the Capitol saved by their valor? Here, where the grim edge of battle joined; here, where all the hope and fear and agony of their country centered; here let them rest, asleep on the Nation’s heart, entombed in the Nation’s love!

Return to The Meaning of Memorial Day.

Post a Comment