Introduction

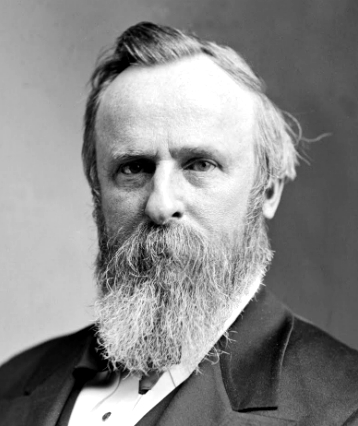

The National Soldiers’ Home in Dayton, Ohio provided a place to care for disabled Civil War veterans. Several such homes were built across the country, but the Dayton site became the largest, and was the first to admit black veterans of the war. It was here, on September 12, 1877, the Country’s Defenders Soldiers’ Monument was unveiled and dedicated, to honor not the great generals but the common American soldier. In attendance was President Rutherford B. Hayes (1822–93). Called upon by the crowd to speak, Hayes reflected on his own experiences as an officer in the Union Army, where he rose to the rank of major general and was wounded at the Battle of South Mountain.

Why is President Hayes impressed by the “glorious” change in the durability of our monuments? How does he connect the change in monuments with changes in understanding the meaning of the battle? Why does the “American private soldier” deserve a monument? What, according to Hayes, is the purpose of monuments? Is Hayes right in saying that “the debt to the dead American soldier can be best paid by the kindness and regard to the living American soldier”? Can monuments make us remember both that debt and what Hayes regards as its “best” payment?

My friends: A few unpremeditated sentences, a little plain soldier’s talk, is all that you will expect. This monument reminds me, and, as I mention it, will remind very many in this great audience, of the first soldier’s monument that was erected in 1861. You all remember what they were. All who took part in those first battles of the great conflict, you remember and can never forget the feelings of sadness with which we saw the remains of our dead comrades gathered up and placed in their last resting place. They were gathered up, you know, by the parties detailed to bury the dead carefully, respectfully and tenderly, and when the shallow grave had been dug, and in their uniforms they had been laid away and covered over, their comrades looked about to see what memento they could leave, and they left frail fragments of cracker boxes, marking with a pencil the name of the regiment and company of the dead comrade, hoping that they would in some way be useful, little perhaps dreaming at the time that to the private soldier should be erected with granite and marble and brass such a structure as we now behold and behold the change. Instead of that little fragment, perishable and fragile, we have these enduring monuments forever to gaze upon. How glorious the change. Does it not remind us of the growth in the sentiment of all mankind of the appreciation of the worth that these men did?

Then we hardly knew what was to be the result of it all, but now we know that these men were fighting the battle of freedom for all mankind; now we know that they have secured to liberty and peace the best part of the best continent on the globe. As this work compares with the frail cracker-box memorials, so does the work which they have done compare with any conception of it which we then could have had. Forever hereafter we shall remember the American private soldier as having established a free nation where every man has an equal chance and fair start in the race of life. This is the work of the American private soldier, and as that monument teaches many lessons let us not forget this one. It is a monument to remind us that many are still living of that great army, who are the victims of that war. Some have lost limbs, some have lost habits and characteristics which enable men to succeed in life. Wherever they are, let us remember always the debt to the dead American soldier can be best paid by the kindness and regard to the living American soldier.

Return to The Meaning of Memorial Day.

Post a Comment