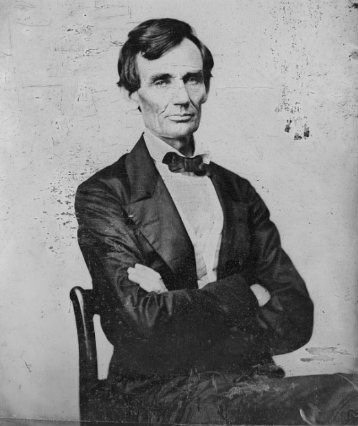

Return to The Meaning of Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday.

Forward the Link

You want to share the page? Add your friend's email below.

A Stepmother’s Recollection

Introduction

Return to The Meaning of Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday.

Post a Comment