Waifs, Isobel Bailey called her Christmas Day guests. This year she had three coming, three waifs—a woman, an elderly man, and a young man—respectable people, well brought up, gentle-looking, neatly dressed, to all appearances the same as everybody else, but lost just the same. She had a private list of such people, not written down, and she drew on it every year as the holiday season descended. Her list of waifs did not grow shorter. Indeed, it seemed to lengthen as the years went by, and she was still young, only thirty-one. What makes a waif, she thought (most often as winter came on, always at Christmas); what begins it? When do people get that fatal separate look? Are waifs born?

Once she had thought that it was their lack of poise that marked them—because who ever saw a poised waif? You see them defiant, stiff, rude, silent, but aren’t they always bewildered? Still, bewilderment was not a state reserved for waifs only. Neither was it, she decided, a matter of having no money, though money seemed to have a great deal to do with it. Sometimes you could actually see people change into waifs, right before your eyes. Girls suddenly became old maids, or at least they developed an incurably single look. Cheerful, bustling women became dazed widows. Men lost their grip and became unsure-looking. It wasn’t any one thing that made a waif. Isobel was sure of that. It wasn’t being crippled, or being in disgrace, or even not being married. It was a shameful thing to be a waif, but it was also mysterious. There was no accounting for it or defining it, and over and over again she was drawn back to her original idea—that waifs were simply people who had been squeezed off the train because there was no room for them. They had lost their tickets. Some of them never had owned a ticket. Perhaps their parents had failed to equip them with a ticket. Poor things, they were stranded. During ordinary days of the year, they could hide their plight. But at Christmas, when the train drew up for that hour of recollection and revelation, how the waifs stood out, burning in their solitude. Every Christmas Day (said Isobel to herself, smiling whimsically) was a station on the journey of life. There on the windy platform the waifs gathered in shame, to look in at the fortunate ones in the warm, lighted train. Not all of them stared in, she knew; some looked away. She, Isobel, looked them all over and decided which ones to invite into her own lighted carriage. She liked to think that she occupied a first-class carriage—their red brick house in Bronxville, solid, charming, waxed and polished, well heated, filled with flowers, stocked with glass and silver and clean towels.

Isobel believed implicitly in law, order, and organization. She believed strongly in organized charity. She gave regular donations to charity, and she served willingly and conscientiously on several committees. She felt it was only fair that she should help those less fortunate than herself, though there was a point where she drew the line. She never gave money casually on the street, and her maids had strict orders to shut the door to beggars. “There are places where these people can apply for help,” she said.

It was different with the Christmas waifs. For one thing, they were not only outside society, they were outside organized charity. They were included in no one’s plans. And it was in the spirit of Christmas that she invited them to her table. They were part of the tradition and ceremony of Christmas, which she loved. She enjoyed decking out the tree, and eating the turkey and plum pudding, and making quick, gay calls at the houses of friends, and going to big parties, and giving and receiving presents. She and Edwin usually accepted an invitation for Christmas night, and sometimes they sent out cards for a late, small supper, but the afternoon belonged to the waifs. She and Edwin had so much, she felt it was only right. She felt that it was beautifully appropriate that she should open her house to the homeless on Christmas Day, the most complete day of the year, when everything stopped swirling and the pattern became plain.

Isobel’s friends were vaguely conscious of her custom of inviting waifs to spend Christmas afternoon. When they heard that she had entertained “poor Miss T.” or “poor discouraged Mr. F.” at her table, they shook their heads and reflected that Isobel’s kindness was real. It wasn’t assumed, they said wonderingly. She really was kind.

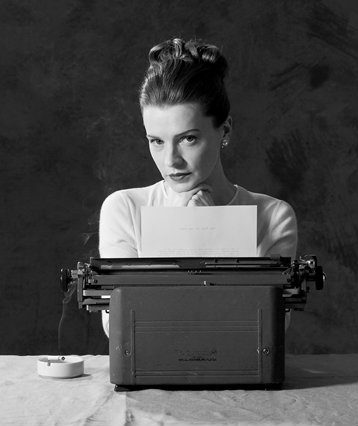

The first of this year’s waifs to arrive was Miss Amy Ellis, who made blouses for Isobel and little silk smocks for Susan, Isobel’s five-year-old daughter. Isobel had never seen Miss Ellis except in her workroom, where she wore, summer and winter, an airy, arty smock of natural-color pongee.[1] Today, she wore a black silk dress that was draped into a cowl around her shoulders, leaving her arms bare. And Miss Ellis’s arms, Isobel saw at once, with a lightning flash of intuition, were the key to Miss Ellis’s character, and to her life. Thin, stringy, cold, and white, stretched stiff with emptiness—they were what made her look like a waif. Could it be that Miss Ellis was a waif because of her arms? It was a thought. Miss Ellis’s legs matched her arms, certainly, and it was easy to see, through the thin stuff of her dress, that her shoulders were too high and pointed. Her neck crept disconsolately down into a hollow and discolored throat. Her greeny-gold hair was combed into a limp short cap, betraying the same arty spirit that inspired her to wear the pongee smock. Her earrings, which dangled, had been hammered out of some coal-like substance. Her deep, lashless eyes showed that she was all pride and no spirit. She was hopeless. But it had all started with her arms, surely. They gave her away.

Miss Ellis had brought violets for Isobel, a new detective story for Edwin, and a doll’s smock for Susan. She sat down in a corner of the sofa, crossed her ankles, expressed pleasure at the sight of the fire, and accepted a Martini from Edwin. Edwin Bailey was thirty-seven and a successful corporation lawyer. His handshake was warm and firm, and his glance was alert. His blond hair was fine and straight, and his stomach looked as flat and hard as though he had a board thrust down inside his trousers. He was tall and temperate. The darkest feeling he acknowledged was contempt. Habitually he viewed the world—his own world and the world reflected in the newspapers—with tolerance. He was unaware of his wife’s theories about Christmas waifs, but he would have accepted them unquestioningly, as he accepted everything about Isobel. “My wife is the most mature human being I have ever met,” he said sometimes. Then, too, Isobel was never jealous, because jealousy was childish. And she was never angry. “But if you understand, really understand, you simply cannot be angry with people,” she would say, laughing.

Now she set about charming Miss Ellis, and Edwin had settled back lazily to watch them when the second waif, Vincent Lace, appeared in the doorway. He sprinted impetuously across the carpet and, without glancing to the right or to the left, fell on both knees before Susan, who was curled on the hearth rug, undressing her new doll.

“Ah, the grand little girl!” cried Vincent. “Sure she’s the living image of her lovely mother! And what name have they put on you, love?”

“Susan,” said the child coldly, and she got up and went to perch under the spreading branches of the splendid tree that blazed gorgeously from ceiling to floor between two tall windows. Beyond the windows, the narrow street lay chill and gray, except when the wind, blowing down the hill, swept before it a ragged leaf of Christmas tissue paper, red or green, or a streamer of colored ribbon.

Undisturbed by the child’s desertion, Vincent rocked back on his plump behind, and wrapped his arms around his knees, and favored his host, then Miss Ellis, and, finally, Isobel with a dazzling view of his small, decaying teeth.

“Well, Isobel,” he murmured, “little Isobel of the peat-brown eyes. You still have the lovely eyes, Isobel. But what am I thinking of at all!” he shouted, bounding to his feet. “Sure your husband will think me a terrible fellow entirely. Forgive me, Isobel, but the little girl took my breath away. She’s yourself all over again.”

“Edwin, this is our Irish poet,” Isobel said. “Vincent Lace, a dear friend of Father’s. I see you still wear the red bow tie, Vincent, your old trademark. I noticed it first thing when I ran into you the other day. As a matter of fact, it was the tie that caught my attention. You were never without it, were you.”

“Ah, we all have our little conceits, Isobel,” Vincent said, smiling disarmingly at Edwin.

Vincent’s face appeared to have been vigorously stretched, either by too much pain or by too much laughter, and when he was not smiling his expression was one of dignified truculence. He was more obviously combed and scrubbed than a sixty-three-year-old man should be, and his bright-blue eyes were anxious. Twenty years ago, he had come from Ireland to do a series of lectures on Irish literature at colleges and universities all over the United States. In his suitcase, he carried several copies of the two thin volumes of poetry that had won him his contract.

“My poems drive the fellows at home stark mad,” Vincent had confided to Isobel’s father, the first time he visited their house. “I pay no attention to the modern rubbish at all. All that crowd thinks of is making pretty-sounding imitations of Yeats and his bunch. Yeats, Yeats, Yeats, that’s all they know. But my masters are long since dead. I go back in spirit to those grand eighteenth-century souls who wandered the bogs and hills of our unfortunate country, and who broke bread with the people, and who wrote out of the heart of the people.”

At this point (for it was a speech Isobel and the others were often to hear), he would leap to his feet and intone in his native Irish tongue the names of the men he admired, and with every syllable his voice would grow more laden, until at the last it seemed that he would have to release a sob, but he never did, although his small blue eyes would be wet and angry. With his wild black hair, his red tie, and his sharp tongue, he quickly became a general favorite, and when his tour was over, he accepted an offer from one of the New York universities and settled down among his new and hospitable friends. Isobel’s father, who had had an Irish grandmother, took to Vincent at once, and there had been a period, Isobel remembered, when her mother couldn’t plan a dinner without being forced to include Vincent. At the age of fifty, he had lost his university post. Everyone knew it was because he drank too much, but Vincent blamed it on some intrigue in the department. He was stunned. He had never thought such a thing could happen to him. Isobel remembered him shouting at her father across the dinner table, “They’ll get down on their knees to me! I’ll go back on my own terms!” Then he had put his head in his hands and cried, and her mother had got up and left the room in disgust. Isobel remembered that he had borrowed from everyone. After her father died, her family dropped Vincent. Everyone dropped him. He made too much of a nuisance of himself. Occasionally, someone would report having seen him in a bar. He was always shouting about his wrongs. He was no good, that was the sum of it. He never really had been any good, although his quick tongue and irreverent air had given him the appearance of brilliance.

A month before, Isobel had run into him on the street, their first meeting for many years. Vincent is a waif, she had thought, looking at him in astonishment. Vincent, the eloquent, romantic poet of her childhood, an unmistakable waif. It was written all over him. It was in every line of his seedy, imploring face. Two days before Christmas, she had invited him to dinner. He was delighted. He had arrived in what he imagined to be his best form—roguish, teasing, sly, and melancholy.

Edwin offered him a Martini, and he said fussily that he was on the wagon. “I will take a cigarette, though,” he said, and selected one from the box on the table beside him. Isobel found with disagreeable surprise that she remembered his hands, which were small and stumpy, with long pared nails. Dreadful hands. She wondered what wretchedness they had brought him through in the years since she had known him. And the famous bow tie, she thought with amusement—how poorly it goes under that fat, disappointed face. Clinging to that distinctive tie, as though anyone connected him with the tie, or with anything any more.

* * *

The minute Jonathan Quin walked into the room, Isobel saw that she could expect nothing from him in the way of conversation. He will be no help at all, she thought, but this did not matter to her, because she never expected much from her Christmas guests. At a dinner party a few days before, she had been seated next to a newspaper editor and had asked him if there were any young people on his staff who might be at a loose end for Christmas. The next day, he had telephoned and given her Jonathan’s name, explaining that he was a reporter who had come to New York from a little town in North Carolina and knew no one.

At first, entering the soft, enormous, firelit room, Jonathan took Miss Ellis to be his hostess, because of her black dress, and then, confused over his mistake, he stumbled around, looking for a chair to hide in. His feet were large. He wore loose, battered black shoes that had been polished until every break and scratch showed. He had put new laces in the shoes. Edwin asked him a few encouraging questions about his work on the newspaper, and he nodded and stammered and joggled his drink and finally told them that he was finding the newspaper a very interesting place.

Vincent said, “That’s a magnificent scarlet in your dress, Isobel. It suits you. A triumphant, regal color it is.”

Isobel, who was sitting in a yellow chair, with her back to the glittering tree, glanced down at her slim wool dress.

“Christmas red, Vincent. I think it is the exact red for Christmas, don’t you? I wore it decorating the tree last night.”

“And my pet Susan dressed up in the selfsame color, like a little red berry she is!” cried Vincent, throwing his intense glance upon the silent child, who ignored him. He was making a great effort to be the witty, rakish professor of her father’s day, and at the same time deferring slyly to Edwin. He did not know that this was to be his only visit, no matter how polite he proved himself to be.

It was a frightful thing about Vincent, Isobel thought. But there was no use getting involved with him. He was too hard to put up with, and she knew what a deadly fixture he could become in a household. “Some of those ornaments used to be on the tree at home, Vincent,” she said suddenly. “You might remember one or two of them. They must be almost as old as I am.”

Vincent looked at the tree and then said amiably, “I can’t remember what I did last year. Or perhaps I should say I prefer not to remember. But it was very kind of you to think of me, Isobel. Very kind.” He covertly watched the drinks getting lower in the glasses.

Isobel began to think it had been a mistake to invite him. Old friends should never become waifs. It was easier to think about Miss Ellis, who was, after all, a stranger. Pitiful people, she thought. How they drag their wretched lives along with them. She allowed time for Jonathan to drink one Martini—one would be more than enough for that confused head—before she stood up to shepherd them all in to dinner.

The warm pink dining room smelled of spice, of roasting turkey, and of roses. The tablecloth was of stiff, icy white damask, and the centerpiece—of holly and ivy and full-blown blood-red roses—bloomed and flamed and cast a hundred small shadows trembling among the crystal and the silver. In the fireplace a great log, not so exuberant as the one in the living room, glowed a powerful dark red.

Vincent startled them all with a loud cry of pleasure. “Isobel, Isobel, you remembered!” He grasped the back of the chair on which he was to sit and stared in exaggerated delight at the table.

“I knew you’d notice,” Isobel said, pleased. “It’s the centerpiece,” she explained to the others. “My mother always had red roses and holly arranged just like that in the middle of our table at home at Christmas time. And Vincent always came to Christmas dinner, didn’t you, Vincent?”

“Christmas dinner and many other dinners,” Vincent said, when they were seated. “Those were the happiest evenings of my life. I often think of them.”

“Even though my mother used to storm down in a rage at four in the morning and throw you out, so my father could get some sleep before going to court in the morning,” Isobel said slyly.

“We had some splendid discussions, your father and I. And I wasn’t always thrown out. Many a night I spent on your big red sofa. Poor old Matty used to find me there, surrounded by glasses and ashtrays and the books your father would drag down to prove me in the wrong, and the struggle she used to have getting me out before your mother discovered me! Poor Matty, she lived in fear that I’d fall asleep with a lighted cigarette going, and burn the house down around your ears. But I remember every thread in that sofa, every knot, I should say. Who has it now, Isobel? I hope you have it hidden away somewhere. In the attic, of course. That’s where you smart young things would put a comfortable old piece of furniture like that. The most comfortable bed I ever lay on.”

Delia, the bony Irish maid, was serving them so discreetly that every movement she made was an insertion. She fitted the dishes and plates onto the table as though they were going into narrow slots. Her thin hair was pressed into stiff waves under her white cap, and she appeared to hear nothing, but she already had given Alice, the cook, who was her aunt, a description of Vincent Lace that had her doubled up in evil mirth beside her hot stove. Sometimes Isobel, hearing the raucous, jeering laughter of these two out in the kitchen, would find time to wonder about all the reports she had ever heard about the soft voices of the Irish.

“Isobel tells me you’ve started a bookshop near the university, Mr. Lace,” Edwin said cordially. “That must be interesting work.”

“Well, now, I wouldn’t exactly say I started it, Mr. Bailey,” Vincent said. “It’s only that they needed someone to advise them on certain phases of Irish writing, and I’m helping to build up that department in the store, although of course I help out wherever they need me. I like talking to the customers, and then I have plenty of time for my own writing, because I’m only obliged to be there half the day. Like all decent-minded gentlemen of leisure, I dabble in writing, Mr. Bailey. And speaking of that, I had a note the other day from an old student of mine who had through some highly unlikely chance come across my name in the Modern Encyclopaedia. An article on the history of house painting, Isobel. What do you think of that? Mr. Quin and Miss Ellis, Isobel and her father knew me as an accomplished and, if I may say so, a reasonably witty exponent of Irish letters. Students fought with tooth and with nail to hear my lecture on Irish writers . . . . ‘Envy Is the Spur,’ I called it. But to get back to my ink-stained ex-student, whose name escapes me. He wanted to know if I remembered a certain May morning when I led the entire student body, or as many as I could lure from the library and from the steps of the building, down to riot outside Quanley’s—a low and splendid drinking establishment of that time, Mr. Quin—to riot, I repeat, for one hour, in protest against their failure to serve me, in the middle hours of the same morning, the final glass that I felt to be my due.”

“Well, that must have been quite an occasion, Mr. Lace, I should imagine,” Miss Ellis said.

Vincent turned his excited stare on Isobel. “You wouldn’t remember that morning, Isobel.”

“I couldn’t honestly say if I remember it or not, Vincent. You had so many escapades. There seemed to be no end to your ingenuity.”

“Oh, I was a low rascal. Miss Ellis, I was a scoundrelly fellow in those days. But when I lectured, they listened. They listened to me. Isobel, you attended one or two of my lectures. I flatter myself now that I captivated even you with my masterly command of the language. Isobel, tell your splendid husband, and this gracious lady, and this gracious youth, that I was not always the clown they see before them now. Justify your old friend, Isobel.”

“Vincent, you haven’t changed at all, have you?”

“Ah, that’s where you’re wrong, Isobel. For I have changed a great deal. Your father would see it. You were too young. You don’t remember. You’re all too young,” he finished discontentedly.

Miss Ellis moved nervously and seemed about to speak, but she said nothing. Edwin asked her if she thought the vogue for mystery stories was as strong as ever, and Vincent looked as if he were about to laugh contemptuously—Isobel remembered him always laughing at everything anyone said—but he kept silent and allowed the discussion to go on.

Isobel reflected that she had always known Vincent to be talky but surely he couldn’t have always been the windbag he was now. Again she wished she hadn’t invited him to dinner, but then she noticed how eagerly he was enjoying the food, and she relented. She was glad that he should see what a pleasant house she had, and that he should have a good meal.

* * *

Isobel was listening dreamily to Vincent’s story about a book thief who stole only on Tuesdays, and only books with yellow covers, and she was trying to imagine what color Miss Ellis’s lank hair must originally have been, when she became aware of Delia, standing close at her side and rasping urgently into her ear about a man begging at the kitchen door.

“Edwin,” Isobel interrupted gently, “there’s a man begging at the back door, and I think, since it’s Christmas, we should give him his dinner, don’t you?”

“What did he ask you for, Delia?” Edwin asked.

“He asked us would we give him a dollar, sir, and then he said that for a dollar and a half he’d sing us our favorite hymn,” Delia said, and began to giggle unbecomingly.

“Ask him if he knows ‘The boy stood on the burning deck,’” Vincent said.

“Poor man, wandering around homeless on Christmas Day!” Miss Ellis said.

“Get an extra plate, so that Mr. Bailey can give the poor fellow some turkey, Delia!” Isobel cried excitedly. “I’m glad he came here! I’m glad we have the chance to see that he has a real Christmas dinner! Edwin, you’re glad, too, although you’re pretending to disapprove!”

“All right, Isobel, have it your own way,” Edwin said, smiling.

He filled the stranger’s plate, with Delia standing judiciously by his elbow. “Give him more dressing, Edwin,” Isobel said. “And Delia, see that he has plenty of hot rolls. I want him to have everything we have.”

“Nothing to drink, Isobel,” Edwin said. “If he hasn’t been drinking already today, I’m not going to be responsible for starting him off. I hope you people don’t think I’m a mean man,” he added, smiling around the table.

“Not at all, Mr. Bailey,” Miss Ellis said stoutly. “We all have our views on these matters. That’s what makes us different. What would the world be like if we were all the same?”

“My mother says,” said Jonathan hoarsely, putting one hand into his trouser pocket, “that if a person is bad off enough to ask her for something, he’s worse off than she is.”

“Your mother must be a very nice lady, Mr. Quin,” Miss Ellis said.

“It’s a curious remark, of Mr. Quin’s mother,” Vincent said moodily.

“Oh, of course you’d have him in at the table here and give him the house, Vincent!” Isobel cried in great amusement. “I remember your reputation for standing treat and giving, Vincent.”

“Mr. Lace has the look of a generous man,” Miss Ellis said, with her thin, childlike smile. The heavy earrings hung like black weights against her thin jaw.

Vincent stared at her. “Isobel remarks that I would bid the man in and give him the house,” he said bitterly. “But at the moment, dear lady, I am not in the position to give him the leg of a chair, so the question hardly arises. Do you know what I would do if I was in Mr. Bailey’s position, Miss Ellis? Now this is no reflection on you, Mr. Bailey. When I think of him, and what is going on in his mind at this moment, as he gazes into the heaped platter that you have so generously provided—”

“Vincent, get back to the point. What would you do in Edwin’s place?” asked Isobel good-naturedly.

Vincent closed his mouth and gazed at her. “You’re quite right, my dear,” he said. “I tend to sermonize. It’s the strangled professor in me, still writhing for an audience. Well, to put it briefly, if I were in your husband’s excellent black leather shoes, I would go out to the kitchen, and I would empty my wallet, which I trust for your sake is well filled, and I would tell that man to go in peace.”

“And he would laugh at you for a fool,” Edwin said sharply.

“And he would laugh at me for a fool,” Vincent said, “and I would know it, and I would curse him, but I would have done the only thing I could do.”

“I don’t get it,” Jonathan said, with more self-assurance than before.

“Oh, Mr. Quin, Vincent is an actor at heart,” Isobel said. “You should have come to our home when my father was alive. It was a one-man performance every time, Vincent’s performance.”

“I used to make you laugh, Isobel.”

“Of course you did,” Isobel said soothingly.

She sat and watched them all eat their salad, wondering at the same time how the man in the kitchen must feel, to come from the cold and deserted winter street into her warm house. He must be speechless at his good fortune, she thought, and she had a wild impulse to go out into the kitchen and see him for herself. She stood up and said, “I want to see if our unexpected guest has enough of everything.”

She hurried through the pantry and into the white glare of the kitchen, where it was very hot. She rigidly avoided looking at the table, but she was conscious of the strange man’s dark bulk against her white muslin window curtains, and of the harsh smell of his cigar. She wanted him to see her, in her red dress, with her flushed face and her sweet, expensive perfume. She owned the house. He had the right to feast his eyes on her. This was the stranger, the classical figure of the season, who had come unbidden to her feast.

Fat-armed Alice was petting the round brown pudding where a part of it had broken away as she tumbled it out of its cloth into its silver dish. Delia stood watching intently, holding away to her side—as though it were a matador’s cape—the stained and steaming cloth.

“Take your time, Alice,” Isobel said in her clear, nicely tempered voice. “Everything is going splendidly. It couldn’t be a more successful party.”

“That’s very considerate of you, Ma’am,” Alice said, letting her eyes roll meaningfully in the direction of the stranger, as though she were tipping Isobel off.

As she turned to leave the kitchen, Isobel saw the man at the table. She did not mean to see him. She had no intention of looking at him, but she did look. She saw that he had hair and hands, and she knew that he had sight, because she felt his eyes on her, but she could not have given a description of him, because in that rapid, silent glance all she really saw was the thick, filthy stub in his smiling mouth.

His cigar, she thought, sitting down again in the dining room. She leaned forward and took a sip of wine. Miss Ellis’s arms, Vincent’s bow tie, this boy’s broken shoes, and now the beggar’s cigar.

* * *

“How is our other guest getting along out there, Delia?” Isobel asked when the salad plates were being cleared away.

“Ah, he’s all right, Ma’am. He’s sitting there and smiling to himself. He’s very quiet, so he is.”

“Has he said nothing at all, Delia?”

“Only when he took an old cigar butt he has out of his pocket. He said to Alice that he strained his back picking it up. He said he made a promise to his mother never to step down off the sidewalk to pick up a butt of a cigar or a cigarette, and he says this one was halfway out in the middle of the street.”

“He must have hung on to a lamp-post!” Jonathan cried, delighted.

“Edwin, send a cigar to that poor fellow when Delia comes in again, will you?” Isobel said. “I’d like to feel he had something decent to smoke for once.”

Delia came in, proudly bearing the flaming pudding, and Edwin told her to take a cigar for the man in the kitchen.

“And don’t forget an extra plate for his pudding, Delia,” Isobel said happily.

“Oh, your mother was a mighty woman, Isobel,” Vincent said, “even though we didn’t always see eye to eye.”

“Well, I’m sure you agreed on the important things, Mr. Lace,” Miss Ellis said warmly.

“I don’t like to disappoint or disillusion you, Miss Ellis, but it was on the important things we disagreed. She thought they were unimportant.”

A screech of surprise and rage was heard from the kitchen, which up to that time had sent to their ears only the subdued and pleasant tinkling of glasses and dishes and silver. They were therefore prepared for—indeed, they compelled, by their paralyzed silence—the immediate appearance of Delia, who materialized without her cap, and with her eyes aglow, looking as though she had been taken by the hair and dropped from a great height.

“That fellow out there in the kitchen!” she cried. “He’s gone!”

“Did he take something?” asked Edwin keenly.

“No, sir. At least, now, I don’t think he took anything. I’ll look and see this minute.”

“Delia, calm yourself,” Isobel said. “What was all the noise about?”

“He flew off when I was in here with the pudding, Ma’am. I went out to give him the cigar Mr. Bailey gave me for him, and he was gone, clean out of sight. I ran over to the window, thinking to call him back for his cigar, as long as I had it in my hand, and there wasn’t a sign of him anywhere. Alice didn’t even know he was out of the chair till she heard the outside door bang after him.”

“Now, Delia. It was rude of him to run off like that when you and Alice and all of us have been at such pains to be nice to him, but I’m sure there’s no need for all this silly fuss,” Isobel said, with an exasperated grimace at Edwin.

“But Mrs. Bailey, he didn’t just go!” Delia said wildly.

“Well, what did he do, then?” Edwin asked.

“Oh, sir, didn’t he go and leave his dirty old cigar butt stuck down in the hard sauce, sir!” Delia cried. She put her hands over her mouth and began to make rough noises of merriment and outrage while her eyes swooped incredulously around the table.

Edwin started to rise, but Isobel stopped him with a look. “Delia,” she said, “tell Alice to whip up some kind of sauce for the pudding and bring it in at once.”

“Oh dear, how could he do such a thing?” Miss Ellis whispered as the door swung to on Delia. “And after you’d been so kind to him.” She leaned forward impulsively to pat Isobel’s hand.

“A shocking thing!” Vincent exclaimed. “Shocking! It’s a rotten class of fellow would do a thing like that.”

“You mustn’t let him spoil your lovely dinner, Mrs. Bailey,” Miss Ellis said. Then she added, to Edwin, “Mrs. Bailey is such a person!”

“I never cared much for hard sauce anyway,” Jonathan said.

“I don’t know what you’re all talking about!” Isobel cried.

“We wouldn’t blame you if you were upset,” Vincent said. “But just because some stupid clod insults you is no reason for you to feel insulted.”

“I think that nasty man meant to spoil our nice day,” Miss Ellis said contentedly. “And he hasn’t at all, has he?”

“Let’s all just forget about it,” Edwin said. “Isn’t that right, Miss Ellis?”

“Are you people sympathizing with me?” Isobel said. “Because if you are, please stop it. I am not in the least upset, I assure you.” With hands that shook violently, she began to serve the pudding.

When they had all been served, she pushed her chair back and said, “Edwin, I have to run upstairs a minute to check on the heat in Susan’s room before she goes for her nap. Delia will bring the coffee inside, and I’ll be down in a second.”

* * *

Upstairs, in the bedroom, she cooled her beleaguered forehead with eau de cologne. She heard the chairs moving in the dining room, and then the happy voices chorusing across the hall. A moment later, she imagined she could hear the chink of their coffee cups. She wished bitterly that it was time to send them all home. She was tired of them. They talked too much. It seemed twenty years since Edwin had carved the turkey.

[1] Silk of a slightly uneven weave made from filaments of wild silk woven in natural tan color.

Return to The Meaning of Christmas Day

Post a Comment