Your club has well and wisely acted in making this the commencement of an annual observance of Mr. Lincoln’s Birthday. The day should be made national like the Birth day of Washington. Let each be appropriately observed, as one of the best things to inculcate upon those who, in the ages, shall come after us. It is patriotic to do so, and it serves to promote a love of country and keep alive and fresh a memory of Patriotic men.

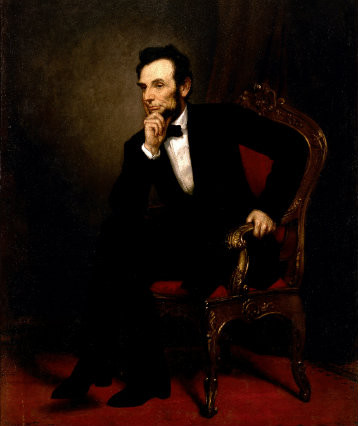

In 1951, a Presidents Day National Committee was formed by Harold Stonebridge Fischer. He lobbied for the creation of a day honoring all presidents to be celebrated March 4, the original inauguration date. This act was defeated in the Senate Judiciary Committee, on the grounds that the holiday would be too close to Lincoln’s and Washington’s birthdays. Though not federally enacted, many state governors liked the idea and proclaimed Presidents Day a holiday. Establishing Lincoln’s birthday as a federal holiday was further complicated by the passing of the 1968 Uniform Holiday Act, which moved several federal holidays, including Memorial Day and Washington’s Birthday, to specific Mondays throughout the year in order to create more three-day weekends. Eventually, individual states created their own Presidents Day holidays to be observed on the third Monday in February. This celebration has been enacted in some fashion by 38 states, though never federally, and each varies by state. While some mark the day as a specific remembrance of Washington and Lincoln (like Arizona), others view it as a day of general recognition for all U.S. presidents. Alabama celebrates Washington and Jefferson as opposed to the more common combination of Washington and Lincoln. A few states observe Washington’s Birthday in February and then celebrate Presidents Day in a different month, for example, the day after Thanksgiving in New Mexico and December 24 in Indiana and Georgia. Eighteen states don’t specify at all what Presidents Day celebrates. Presidents Day has also gained some national recognition from retailers, who use the long weekend to offer sales. A few state governments have enacted legislation recognizing Lincoln’s birthday on February 12 as its own official holiday. Most notably, Illinois, the “Land of Lincoln” and his adopted home state, celebrates Lincoln’s birthday as an official school holiday, along with a few other states including New York, Connecticut, and Missouri. However, this number has declined in recent years, when both California and New Jersey ended the celebration of Lincoln’s birthday as paid holidays to cut budgetary costs. Unfortunately, more states now celebrate Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving, as a holiday for state employees than celebrate Lincoln’s birthday. Even without an official national holiday, Lincoln remains among the most admired American presidents. His face is printed on the five-dollar bill and stamped on the penny. He has national shrines in three states, including one of America’s most iconic landmarks—the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC. Though not federally recognized, Lincoln’s birthday is still commemorated by Americans. Wreaths are laid at notable Lincoln landmarks throughout the United States, including his birthplace in Kentucky, his tomb in Springfield, Illinois, and the Lincoln Memorial—the walls of which are still inscribed with this promise:In this Temple

As In The Hearts Of The People

For Whom He Saved The Union

The Memory of Abraham Lincoln

Is Enshrined Forever.

Return to The Meaning of Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday.

Post a Comment