Introduction

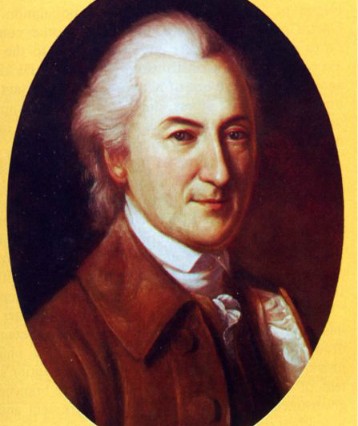

John Dickinson (1732–1808), known as the “Penman of the Revolution” for his Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, was, at various times, a militia officer in the Revolutionary War, a member of the First and Second Continental Congresses, a primary drafter of the Articles of Confederation, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, and the state president of Delaware (1781) and Pennsylvania (1782).

His pre-Revolutionary song, “The Liberty Song,” is set to the tune of “Heart of Oak,” the anthem of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom. Dickinson sent the words he composed for the song to his Massachusetts friend James Otis, saying, “I enclose you a song for American freedom. I have long since renounced poetry, but as indifferent songs are very powerful on certain occasions, I venture to invoke the deserted muses.” The song was soon thereafter published in the Boston Gazette, in July 1768; the words that appear here are from its updated 1770 version. Dickinson’s sixth verse marks the first appearance of the patriotic slogan, “united we stand, divided we fall.”

What is the meaning of the “liberty” or “freedom” of which this song speaks? Was John Dickinson right to think that this “indifferent song” could make a “very powerful” difference? Why? Dickinson, as we noted above in “A Brief History of Independence,” later looked for reconciliation with Britain and, at the Continental Congress in 1776, argued (and voted) against declaring independence. What condition of liberty, then, is called for in this song? The final stanza toasts King George’s health and Britannia’s glory and wealth, if somewhat conditionally. Is the song, then, pointing toward a restoration of British liberty or the triumph of a new and separate form of American liberty?

For a musical rendition, view this performance by Adam Eisenstein.

(10 votes, average: 4.10 out of 5)

(10 votes, average: 4.10 out of 5)

Post a Comment