Introduction

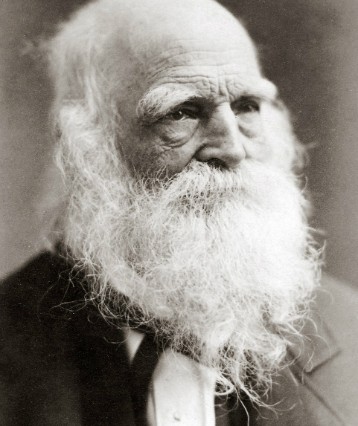

Thinking well about Independence Day requires thinking about freedom—where it comes from and how it is preserved. A moving invitation to such reflection is this 1842 poem by America’s first great poet William Cullen Bryant (1794–1878), lawyer, longtime editor of the New York Evening Post, translator of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and political activist—Bryant was an early supporter of Abraham Lincoln, whom he introduced at New York’s Cooper Union (February 1860) for the speech that would gain Lincoln the presidential nomination. In “The Antiquity of Freedom” Bryant poetically reflects on the history of Freedom and its struggles against its inveterate enemies, Power and Tyranny.

Why does spending time in the woods, with its peaceful shades “immeasurably old,” lead Bryant to think of “the earliest days of liberty”? What was liberty like in its earliest days? What does he mean by saying (third stanza) that freedom was “not given by human hands,” but was “twin-born with man”? Why, in the second stanza, does he present Freedom as an armed warrior, rather than, say, as lady liberty? What is the relationship between Freedom and Power, and how is Freedom able to escape the chains and imprisonment by Power? What gives rise to Tyranny? What (fourth stanza) are the new forms and subtler snares of Tyranny, and why must Freedom remain forever vigilant? The final verses return to the “old and friendly solitudes” of the woods, offered as respite from “tumult and the frauds of men.” What has this natural liberty to do with the freedom celebrated on Independence Day? Is it possible, even if only in thought, to return to the glorious childhood of the human race? Was the glory of humanity’s childhood greater than that of our maturity? Is the ancient and original liberty of nature better than the hard-earned political freedom of self-government?

Here are old trees, tall oaks, and gnarled pines,

That stream with gray-green mosses; here the ground

Was never trenched by spade, and flowers spring up

Unsown, and die ungathered. It is sweet

To linger here, among the flitting birds

And leaping squirrels, wandering brooks, and winds

That shake the leaves, and scatter, as they pass,

A fragrance from the cedars, thickly set

With pale-blue berries. In these peaceful shades—

Peaceful, unpruned, immeasurably old—

My thoughts go up the long dim path of years,

Back to the earliest days of liberty.

O Freedom! thou art not, as poets dream,

A fair young girl with light and delicate limbs,

And wavy tresses gushing from the cap

With which the Roman master crowned his slave

When he took off the gyves. A bearded man,

Armed to the teeth, art thou; one mailéd hand

Grasps the broad shield, and one the sword; thy, brow,

Glorious in beauty though it be, is scarred

With tokens of old wars; thy massive limbs

Are strong with struggling. Power at thee has launched

His bolts, and with his lightnings smitten thee;

They could not quench the life thou hast from heaven;

Merciless Power has dug thy dungeon deep,

And his swart armorers, by a thousand fires,

Have forged thy chain; yet, while he deems thee bound,

The links are shivered, and the prison-walls

Fall outward; terribly thou springest forth,

As springs the flame above a burning pile,

And shoutest to the nations, who return

Thy shoutings, while the pale oppressor flies.

Thy birthright was not given by human hands:

Thou wert twin-born with man. In pleasant fields,

While yet our race was few, thou sat’st with him,

To tend the quiet flock and watch the stars,

And teach the reed to utter simple airs.

Thou by his side, amid the tangled wood,

Didst war upon the panther and the wolf,

His only foes; and thou with him didst draw

The earliest furrow on the mountain-side,

Soft with the deluge. Tyranny himself,

Thy enemy, although of reverend look,

Hoary with many years, and far obeyed,

Is later born than thou; and as he meets

The grave defiance of thine elder eye,

The usurper trembles in his fastnesses.

Thou shalt wax stronger with the lapse of years,

But he shall fade into a feebler age—

Feebler, yet subtler. He shall weave his snares,

And spring them on thy careless steps, and clap

His withered hands, and from their ambush call

His hordes to fall upon thee. He shall send

Quaint maskers, wearing fair and gallant forms

To catch thy gaze, and uttering graceful words

To charm thy ear; while his sly imps, by stealth,

Twine round thee threads of steel, light thread on thread,

That grow to fetters; or bind down thy arms

With chains concealed in chaplets. Oh! not yet

Mayst thou unbrace thy corslet, nor lay by

Thy sword; nor yet, O Freedom! close thy lids

In slumber; for thine enemy never sleeps,

And thou must watch and combat till the day

Of the new earth and heaven. But wouldst thou rest

Awhile from tumult and the frauds of men,

These old and friendly solitudes invite

Thy visit. They, while yet the forest-trees

Were young upon the unviolated earth,

And yet the moss-stains on the rock were new,

Beheld thy glorious childhood, and rejoiced.

Return to The Meaning of Independence Day.

Post a Comment