The enigma of George Washington has never been resolved. Remote, brooding, inaccessible, he stares down from the Houdon statue, bones massive in the nose and jawline, melancholy in the downturn of the mouth. The eyes, wide-set and solemn, look into the middle distance, skirting contact and comprehension, sealing their secret in themselves. The face presents a challenge that intrigues as it baffles and defies. In 1852, from the pit of a dissolving Union, Emerson took this stab into the mystery, seeking in that bleak moment solace from the source: “The heavy, laden eyes stare at you, as the eyes of an ox in pasture. And the mouth has gravity and depth of quiet, as if this MAN had absorbed all the serenity of America, and left none for his restless, rickety, hysterical countrymen.” For two centuries, this strength has brooded over the American democracy in the tense attraction of born opposites: its balance, its counterpoise, its resource—and its reproach.

This strength has been a burden on America, and America has taken its revenge. No great man in history has a name so lifeless or a monument so featureless and blank. Jefferson and Lincoln, adoptive saints of the democracy, dominate their own memorials; Andrew Jackson’s very horse breathes fire; Washington’s tribute alone reveals no warming touch of flesh. The lines describe the limits of the image: flawless aspiration—and what else?

More, apparently, than his countrymen have cared or dared to know. The reality is the inverse of the image, flawed and broken, violent, complex. Incident and irony weave strange and unexpected patterns in his life. He began a great world war when he was twenty-two years old, was branded an “assassin” in the courts of Europe, and chided for barbarity by Voltaire. In the war that followed, his pride, insolence, and insubordination were famous—and infamous—among British and colonial commanders in the skirmishes against the French. Eaten by a fierce ambition, he pursued fame relentlessly, missed it, and discovered later, when it came unbidden, that he had somehow lost the taste. He proposed to one woman while in love with another, married the first in a mood of almost bitter resignation, and found later that this, too, could change. Cool, aloof, and distant, he was known for the cold qualities of what Jefferson called his perfect justice, yet Jefferson, and others, sense the hidden violence; portraitist Gilbert Stuart observed the lineaments of all the strongest passions and said that if he had lived among the Indians, he would have been the most fierce of all the savage chiefs. The results of those banked fires were apparent then and still endure: the army saved, the union soldered, the ambitions, flames, and talents of Hamilton, Jefferson, John Adams—the most contentious lot to coexist in any house of government—overmastered and subdued.

What happened, then, to blur this image, to make this man who tamed the fire-eaters of his lifetime seem so much the dimmest of them all? Sometime after 1775, with the vast portion of his public life before him, he passed into the hands of propagandists and mythmakers, more interested in imagery than in character delineation, more concerned with a totem to hang morals on than in the picture of a flawed and living man. Part was in the temper of the time: the need of a scrabble nation, fighting its own impending dissolution, for a presence to counter its centrifugal forces; something of marble, colder than flesh. Washington himself conspired in his own entombment, refusing to publish his recollections or to let those of the men who knew him see the light of day. “Any memoirs of my life,” he wrote James Craik in 1784 when he was a world-famous figure, as well as the national hero of a state that was not quite a nation, “would rather hurt my feelings than tickle my pride whilst I lived. I had rather glide gently down the stream of life, leaving it to posterity to think and say what they please of me, than by any act of mine to have vanity or ostentation imputed to me. . . . I do not think vanity is a trait of my character.”

In this disavowal lie two preoccupations that bordered on obsessions in themselves: Washington’s social bias against self-aggrandizement and Washington’s fear that any close inspection of his career and character could serve only to underline those deficiencies of temperament and training of which he was so painfully and so persistently aware. At first glance, these insecurities sit oddly with that serenity that impressed Emerson; at second sight they form a balanced pattern of anxiety and accomplishment that governed his emotional development and ruled the inner rhythms of his life. Without the doubts, the achievements would not have been so dazzling, each sense of his own insufficiencies driving him more surely toward his cold ideal. That stoic calm was a forced contrivance wrested out of inner turmoil; Washington had made himself, and then his country, from a tangle of disruptive forces in a prolonged and conscious effort of the will. The strains within the commonwealth are obvious, those within the man less clear. Yet they existed and they too must come to light. . . .

The question remains—how much did he bring upon himself? He had set the machine in motion when he turned from his mother to his half brothers and the ever-wider rhythms of their world. “My inclinations are strongly bent to arms.” For years, he hurled himself at power, clawed for preference, forced himself over and over on the attentions of the colony, the empire, the world. If he failed in his first young objective—to become an ornament of empire—he had set the stage for his wider glories, the pieces ready to fall, at the tipping of fate, into their place. If not the ultra in every department, he was in each succeeding crisis the one man with the combination of requisites to fill a special need—the political choice for the army; the inevitable choice for the state. There was no choice ever for the shy and driven half brother for whom fame and service, duty and ambition were inextricably interwoven and set into his bones and blood. His intermittent efforts at “retirement” (always with a hopeless sound about them) were recuperations, repair between exertions, the background for his efforts, and the necessary relief. In these swings of light and dark are the terrain of his interior, iron and mercury, ambition and diffidence, shadow and sun. Each element had its own place in his greatness, sharpening or softening some native metal, taming power, giving tolerance its bite. His passions, gigantic and troubling, were the bedrock of his genius, controlled to provide discipline, loosened to unleash the welding power that sustained and settled the nation he had helped to form. On these passions, now chained and now explosive, rested the United States.

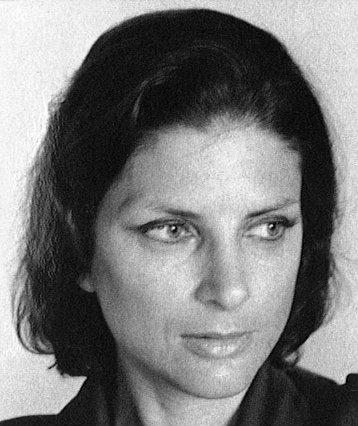

Emery, Noemie. “The Passionate Bedrock of Genius.” From Washington: A Biography. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1976, 13–15, 382–83. Copyright © 1976 by Noemie Emery. Used by permission of the author.

Return to The Meaning of George Washington's Birthday.

Post a Comment