Introduction

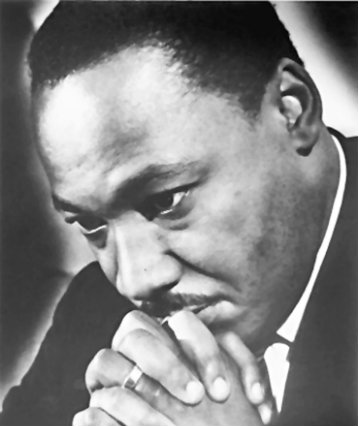

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his now legendary, “I Have a Dream” speech, at “The Great March on Washington,” August 28, 1963, in front of the Lincoln Memorial. The march for “jobs and freedom,” organized by a diverse group of civil rights, labor, and religious organizations, drew more than 200,000 people, becoming one of the largest political rallies for human rights in our history. Many regarded it as crucial to the passage of the Civil Rights Act (1964), as well as the Voting Rights Act (1965). King’s oration—part speech, part sermon, part prophecy—was the high point of the rally, remembered most for his “dream” vision of the future that articulated the aspirations of the Movement.

But the speech as a whole repays close study and raises interesting questions. The speech begins (and ends) by emphasizing freedom: what does King mean by freedom, and in what sense does he regard the Negro as “still not free”? The speech then moves to speak about justice: can you say what he means by “justice”—equality of rights, equality before the law, equality of opportunity, equality of economic and social condition, or something else? How is it related to the Lord’s punitive justice, prophesied by Amos, that “rolls down like waters”? And what is the connection, according to King, between justice and freedom? Might increasing justice for some require limiting freedom for others?

In recounting his dream of the future, King speaks not only of freedom and justice but also of brotherhood and sisterhood: how is this related to the other goals? Is the goal of brotherhood rooted in the American dream of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” or is it rooted in the Christian messianic vision, when “the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together”? Is King, in his remark about the “color of their skin” and the “content of their character,” preaching a vision of color-blind America, where race is irrelevant? Do you share such a vision today? When King concludes with the moving call “Let freedom ring,” does it carry the same meaning as it does in his source, “My Country ’Tis of Thee”? What would it mean to be “free at last”?

Post a Comment