Introduction

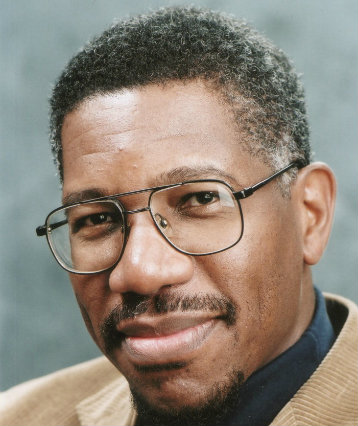

For many years, American blacks have been trying to make sense of their identity as African and American, and much effort has been spent to establish connections to their forgotten African roots, partly in negative reaction to the “imposed” American holidays and Christian rituals, partly in positive search for a lost ancestral culture. In this essay, Gerald Lyn Early (b. 1952), professor of English and head of the African American Studies Program at Washington University in St. Louis, discusses one prominent expression of this search for a more authentic African American culture and religion, the holiday of Kwanzaa.

According to Early, the holiday of Kwanzaa “bestows the gifts of therapy.” What is it that requires therapy? How does the “therapy” work? How well does Early think that Kwanzaa cures or heals? What does he mean by claiming that Kwanzaa “trivializes the very heritage that it is trying to make sacred”? Consider the seven principles/beliefs that inform the holiday of Kwanzaa. Are they at odds with either American or Christian principles? Why does Early, as a Christian, resist the rituals and symbols of Kwanzaa? Why in the end does he relent, appearing to change his mind about the value of the holiday? After expressing gratitude for a “moment of uncontrived human connection”—an undying memory of his sister at a Christmas past—triggered by a recent Kwanzaa celebration, he generalizes: “What else is Kwanzaa, Christmas, or any other holiday, in the end, good for?” Is the main purpose of our national holidays the evoking of private personal memories? Is this why we celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day?

Post a Comment