Introduction

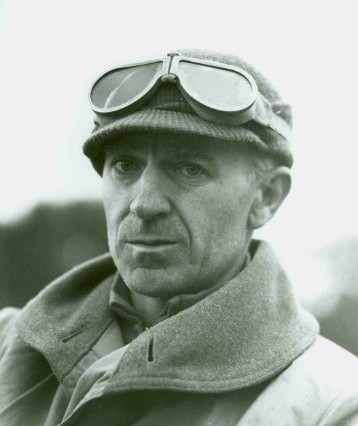

Ernie Pyle (1900–45) was an American journalist and war correspondent known for covering World War II from the soldiers’ perspective. Pyle was killed on April 18, 1945, on le Shima, an island off Okinawa, by Japanese machine-gun fire. In the following columns, Pyle tells of the life and sacrifices of and by the American soldier in World War II.

Brave Men! Brave Men!

“Brave Men, Brave Men!” explores the change that happens to combat veterans as they become used to performing the act their nation asks of them—killing another human being. Do you think that the acquired attitude toward killing described by Pyle is inevitable? Necessary? Desirable? Why? How does a “professional” who kills in the name of and for his country differ—morally and psychologically—from a Mafia “hit man” or a mercenary soldier who fights only for a living? Is Pyle right in saying that only the frontline soldier is “truly at war”? What about the medics or the supply personnel? Can we not say that a nation is truly at war?

NORTHERN TUNISIA, April 22, 1943—I was away from the front lines for a while this spring, living with other troops, and considerable fighting took place while I was gone. When I got ready to return to my old friends at the front I wondered if I would sense any change in them.

I did, and definitely.

The most vivid change is the casual and workshop manner in which they now talk about killing. They have made the psychological transition from the normal belief that taking human life is sinful, over to a new professional outlook where killing is a craft. To them now there is nothing morally wrong about killing. In fact it is an admirable thing.

I think I am so impressed by this new attitude because it hasn’t been necessary for me to make this change along with them. As a noncombatant, my own life is in danger only by occasional chance or circumstance. Consequently I need not think of killing in personal terms, and killing to me is still murder.

Even after a winter of living with wholesale death and vile destruction, it is only spasmodically that I seem capable of realizing how real and how awful this war is. My emotions seem dead and crusty when presented with the tangibles of war. I find I can look on rows of fresh graves without a lump in my throat. Somehow I can look on mutilated bodies without flinching or feeling deeply.

It is only when I sit alone away from it all, or lie at night in my bedroll recreating with closed eyes what I have seen, thinking and thinking and thinking, that at last the enormity of all these newly dead strikes like a living nightmare. And there are times when I feel that I can’t stand it and will have to leave.

* * *

But to the fighting soldier that phase of the war is behind. It was left behind after his first battle. His blood is up. He is fighting for his life, and killing now for him is as much a profession as writing is for me.

He wants to kill individually or in vast numbers. He wants to see the Germans overrun, mangled, butchered in the Tunisian trap. He speaks excitedly of seeing great heaps of dead, of our bombers sinking whole shiploads of fleeing men, of Germans by the thousands dying miserably in a final Tunisian holocaust of his own creation.

In this one respect the front-line soldier differs from all the rest of us. All the rest of us—you and me and even the thousands of soldiers behind the lines in Africa—we want terribly yet only academically for the war to get over. The front-line soldier wants it to be got over by the physical process of his destroying enough Germans to end it. He is truly at war. The rest of us, no matter how hard we work, are not.

The Death of Captain Waskow

In this column, Pyle describes the reactions of soldiers to the newly dead bodies of their comrades, and especially to the corpse of their beloved commanding officer. One might think that men who fight and kill must be aware of the possibility of being killed and hardened to the sight of dead bodies. But are they? Can you account for the reactions of the men to the presence of the newly dead? Describe and try to explain the reactions of the different men to the death of Captain Waskow.

AT THE FRONT LINES IN ITALY, January 10, 1944—In this war I have known a lot of officers who were loved and respected by the soldiers under them. But never have I crossed the trail of any man as beloved as Capt. Henry T. Waskow of Belton, Texas.

Capt. Waskow was a company commander in the 36th Division. He had led his company since long before it left the States. He was very young, only in his middle twenties, but he carried in him a sincerity and gentleness that made people want to be guided by him.

“After my own father, he came next,” a sergeant told me.

“He always looked after us,” a soldier said. “He’d go to bat for us every time.”

“I’ve never knowed him to do anything unfair,” another one said.

I was at the foot of the mule trail the night they brought Capt. Waskow’s body down. The moon was nearly full at the time, and you could see far up the trail, and even part way across the valley below. Soldiers made shadows in the moonlight as they walked.

Dead men had been coming down the mountain all evening, lashed onto the backs of mules. They came lying belly-down across the wooden pack-saddles, their heads hanging down on the left side of the mule, their stiffened legs sticking out awkwardly from the other side, bobbing up and down as the mule walked.

The Italian mule-skinners were afraid to walk beside dead men, so Americans had to lead the mules down that night. Even the Americans were reluctant to unlash and lift off the bodies at the bottom, so an officer had to do it himself, and ask others to help.

The first one came early in the morning. They slid him down from the mule and stood him on his feet for a moment, while they got a new grip. In the half light he might have been merely a sick man standing there, leaning on the others. Then they laid him on the ground in the shadow of the low stone wall alongside the road.

I don’t know who that first one was. You feel small in the presence of dead men, and ashamed at being alive, and you don’t ask silly questions.

We left him there beside the road, that first one, and we all went back into the cowshed and sat on water cans or lay on the straw, waiting for the next batch of mules.

Somebody said the dead soldier had been dead for four days, and then nobody said anything more about it. We talked soldier talk for an hour or more. The dead man lay all alone outside in the shadow of the low stone wall.

Then a soldier came into the cowshed and said there were some more bodies outside. We went out into the road. Four mules stood there, in the moonlight, in the road where the trail came down off the mountain. The soldiers who led them stood there waiting. “This one is Captain Waskow,” one of them said quietly.

Two men unlashed his body from the mule and lifted it off and laid it in the shadow beside the low stone wall. Other men took the other bodies off. Finally there were five lying end to end in a long row, alongside the road. You don’t cover up dead men in the combat zone. They just lie there in the shadows until somebody else comes after them.

The unburdened mules moved off to their olive orchard. The men in the road seemed reluctant to leave. They stood around, and gradually one by one I could sense them moving close to Capt. Waskow’s body. Not so much to look, I think, as to say something in finality to him, and to themselves. I stood close by and I could hear.

One soldier came and looked down, and he said out loud, “God damn it.” That’s all he said, and then he walked away. Another one came. He said, “God damn it to hell anyway.” He looked down for a few last moments, and then he turned and left.

Another man came; I think he was an officer. It was hard to tell officers from men in the half light, for all were bearded and grimy dirty. The man looked down into the dead captain’s face, and then he spoke directly to him, as though he were alive. He said: “I’m sorry, old man.”

Then a soldier came and stood beside the officer, and bent over, and he too spoke to his dead captain, not in a whisper but awfully tenderly, and he said:

“I sure am sorry, sir.”

Then the first man squatted down, and he reached down and took the dead hand, and he sat there for a full five minutes, holding the dead hand in his own and looking intently into the dead face, and he never uttered a sound all the time he sat there.

And finally he put the hand down, and then reached up and gently straightened the points of the captain’s shirt collar, and then he sort of rearranged the tattered edges of his uniform around the wound. And then he got up and walked away down the road in the moonlight, all alone.

After that the rest of us went back into the cowshed, leaving the five dead men lying in a line, end to end, in the shadow of the low stone wall. We lay down on the straw in the cowshed, and pretty soon we were all asleep.

A Long Thin Line of Personal Anguish

In this column, Pyle describes the collection of objects strewn along the Normandy beach, left behind by those who there lost their lives. What do we learn from these leavings about their now deceased owners? Some of the relics—the banjo, the tennis racket—were highly incongruous. Can you understand why the men who carried these items might have done so? What do you think you might have carried with you on the Normandy Invasion? Rank and explain each of your choices. What does that exercise, and this column, tell you about the experience of war?

NORMANDY BEACHHEAD, June 17, 1944—In the preceding column we told about the D-day wreckage among our machines of war that were expended in taking one of the Normandy beaches.

But there is another and more human litter. It extends in a thin little line, just like a high-water mark, for miles along the beach. This is the strewn personal gear, gear that will never be needed again, of those who fought and died to give us our entrance into Europe.

Here in a jumbled row for mile on mile are soldiers’ packs. Here are socks and shoe polish, sewing kits, diaries, Bibles and hand grenades. Here are the latest letters from home, with the address on each one neatly razored out—one of the security precautions enforced before the boys embarked.

Here are toothbrushes and razors, and snapshots of families back home staring up at you from the sand. Here are pocketbooks, metal mirrors, extra trousers, and bloody, abandoned shoes. Here are broken-handled shovels, and portable radios smashed almost beyond recognition, and mine detectors twisted and ruined.

Here are torn pistol belts and canvas water buckets, first-aid kits and jumbled heaps of lifebelts. I picked up a pocket Bible with a soldier’s name in it, and put it in my jacket. I carried it half a mile or so and then put it back down on the beach. I don’t know why I picked it up, or why I put it back down.

Soldiers carry strange things ashore with them. In every invasion you’ll find at least one soldier hitting the beach at H-hour with a banjo slung over his shoulder. The most ironic piece of equipment marking our beach—this beach of first despair, then victory—is a tennis racket that some soldier had brought along. It lies lonesomely on the sand, clamped in its rack, not a string broken.

Two of the most dominant items in the beach refuse are cigarets and writing paper. Each soldier was issued a carton of cigarets just before he started. Today these cartons by the thousand, water-soaked and spilled out, mark the line of our first savage blow.

Writing paper and air-mail envelopes come second. The boys had intended to do a lot of writing in France. Letters that would have filled those blank, abandoned pages.

Always there are dogs in every invasion. There is a dog still on the beach today, still pitifully looking for his masters.

He stays at the water’s edge, near a boat that lies twisted and half sunk at the water line. He barks appealingly to every soldier who approaches, trots eagerly along with him for a few feet, and then, sensing himself unwanted in all this haste, runs back to wait in vain for his own people at his own empty boat.

* * *

Over and around this long thin line of personal anguish, fresh men today are rushing vast supplies to keep our armies pushing on into France. Other squads of men pick amidst the wreckage to salvage ammunition and equipment that are still usable.

Men worked and slept on the beach for days before the last D-day victim was taken away for burial.

I stepped over the form of one youngster whom I thought dead. But when I looked down I saw he was only sleeping. He was very young, and very tired. He lay on one elbow, his hand suspended in the air about six inches from the ground. And in the palm of his hand he held a large, smooth rock.

I stood and looked at him a long time. He seemed in his sleep to hold that rock lovingly, as though it were his last link with a vanishing world. I have no idea at all why he went to sleep with the rock in his hand, or what kept him from dropping it once he was asleep. It was just one of those little things without explanation that a person remembers for a long time.

* * *

The strong, swirling tides of the Normandy coastline shift the contours of the sandy beach as they move in and out. They carry soldiers’ bodies out to sea, and later they return them. They cover the corpses of heroes with sand, and then in their whims they uncover them.

As I plowed out over the wet sand of the beach on that first day ashore, I walked around what seemed to be a couple of pieces of driftwood sticking out of the sand. But they weren’t driftwood.

They were a soldier’s two feet. He was completely covered by the shifting sands except for his feet. The toes of his GI shoes pointed toward the land he had come so far to see, and which he saw so briefly.

Pyle, Ernie. “Brave Men, Brave Men!” April 22, 1943. Available online. Reprinted by permission of the Scripps Howard Foundation.

—. “Death of Captain Waskow.” January 10, 1944. Available online. Reprinted by permission of the Scripps Howard Foundation.

—. “A Long Thin Line of Personal Anguish.” June 14, 1944. Available online. Reprinted by permission of the Scripps Howard Foundation.

Return to The Meaning of Memorial Day.

Post a Comment