A new girl came into the Winthrop Avenue public school about the beginning of November, and this is how she looked to the other boys and girls in the seventh grade.

She couldn’t understand English although she could read it enough to get her lessons. (This was a small public school in a small inland American town where they seldom saw any foreigners, and people who couldn’t speak English seemed outlandish.) She wore the queerest-looking clothes you ever saw and clumping shoes and great thick woolen stockings. (All the children in that town, as in most American towns, dressed exactly like everybody else, because their mothers mostly bought their clothes at Benning and Davis’ department store on Main Street.)

Her hair wasn’t bobbed and curled, neither a long nor short bob; it looked as though her folks hadn’t ever had enough sense to bob it. It was done up in two funny looking pigtails. She had a queer expression on her face, like nothing anybody had ever seen—kind of a smile and yet kind of offish. She couldn’t see the point of wise-cracks, but she laughed over things that weren’t funny a bit, like the way a cheerleader waves his arms.

She got her lessons terribly well (the others thought somebody at home must help her more than the teachers like), and she was the dumbest thing about games—didn’t even know how to play duck on a rock or run sheep run. And, queerest of all, she wore aprons! Can you beat it!

That’s how she looked to the school. This is how the school looked to her. They had come a long way, she and her grandfather, from the town in Austria where he had a shop in which he repaired watches and clocks and sold trinkets the peasant boys bought for their sweethearts.

Men in uniforms and big boots had come suddenly one day—it was in vacation, and Magda was there—and had smashed in the windows of the shop and the showcase with the pretty things in it and had thrown all the furniture from their home back of the shop out into the street and made a bonfire of it.

Magda had been hiding in a corner and saw this; and now, after she had gone to sleep, she sometimes saw it again and woke up with a scream, but Grandfather always came quickly to say smilingly, “All right, Magda child. We’re safe in America with Uncle Harry. Go to sleep again.”

He had said she must not tell anybody about that day. “We can do something better in the New World than sow more hate,” he said seriously. She was to forget about it if she could, and about the long journey afterward, when they were so frightened and had so little to eat; and, worst of all, when the man in the uniform in New York thought for a minute that something was wrong with their precious papers and they might have to go back.

She tried not to think of it, but it was in the back of her mind as she went to school every day, like the black cloth the jewelers put down on their counters to make their pretty gold and silver things shine more. The American school (really a rather ugly old brick building) was for Magda made of gold and silver, shining bright against what she tried to forget.

How kind the teachers were! Why, they smiled at the children. And how free and safe the children acted! Magda simply loved the sound of their chatter on the playground, loud and gay and not afraid even when the teacher stepped out for something. She did wish she could understand what they were saying.

She had studied English in her Austrian school, but this swift, birdlike twittering didn’t sound a bit like the printed words on the page. Still, as the days went by she began to catch a word here and there, short ones like “down” and “run” and “back.” And she soon found what hurrah! means, for the Winthrop Avenue school made a specialty of mass cheering, and every grade had a cheerleader, even the first graders.

Madga thought nearly everything in America was as odd and funny as it was nice. But the cheerleaders were the funniest, with their bendings to one side and the other and then jumping up straight in the air till both feet were off the ground. But she loved to yell, “Hurrah!” too, although she couldn’t understand what they were cheering about.

It seemed to her that the English language was like a thick, heavy curtain hanging down between her and her new schoolmates. At first she couldn’t see a thing through it. But little by little it began to have thinner spots in it. She could catch a glimpse here and there of what they were saying when they sometimes stood in a group, looking at her and talking among themselves. How splendid it would be, she thought, to have the curtain down altogether so she could really understand what they were saying!

This is what they were saying—at least the six or seven girls who tagged after Betty Woodworth. Most of the seventh graders were too busy studying and racing around at recess time to pay much attention to the queer new girl. But some did. They used to say, “My goodness, look at that dress! It looks like her grandmother’s—if she’s got one.”

“Of all the dumb clucks. She doesn’t know enough to play squat tag. My goodness, the first graders can play tag.”

“My father told my mother this morning that he didn’t know why our country should take in all the disagreeable folks that other countries can’t stand any more.”

“She’s Jewish. She must be. Everybody that comes from Europe now is Jewish. We don’t want our town all filled up with Jews!”

“My uncle Peter saw where it said in the paper we ought to keep them out. We haven’t got enough for ourselves as it is.”

Magda could just catch a word or two, “country” and “enough” and “uncle.” But it wouldn’t be long now, she thought happily, till she could understand everything they said and really belong to seventh grade.

About two weeks after Magda came to school Thanksgiving Day was due. She had never heard of Thanksgiving Day, but since the story was all written out in her history book she soon found out what it meant. She thought it was perfectly lovely!

She read the story of the Pilgrim Fathers and their long, hard trip across the ocean (she knew something about that trip), and their terrible first winter, and the kind Indian whose language they couldn’t understand, who taught them how to cultivate the fields, and then—oh, it was poetry, just poetry, the setting aside of a day forever and forever, every year, to be thankful that they could stay in America!

How could people (as some of the people who wrote the German textbooks did) say that Americans didn’t care about anything but making money? Why, here, more than three hundred years after that day, this whole school and every other school, everywhere all over the country, were turning themselves upside down to celebrate with joy their great-grandfathers’ having been brave enough to come to America and to stay here, even though it was hard, instead of staying in Europe, where they had been so badly treated. (Magda knew something about that, too.)

Everybody in school was to do something for the celebration. The first graders had funny little Indian clothes, and they were going to pretend to show the second graders (in Puritan costumes) how to plant corn. Magda thought they were delightful, those darling little things, being taught already to be thankful that they could go on living in America.

Some grades had songs; others were going to act in short plays. The children in Magda’s own seventh grade, that she loved so, were going to speak pieces and sing. She had an idea all her own, and because she couldn’t be sure of saying the right words in English she wrote a note to the teacher about it.

She would like to write a thankful prayer (she could read English pretty well now) and learn it by heart and say it, as her part of the celebration. The teacher, who was terrifically busy with a bunch of boys who were to build a small “pretend” log cabin on stage, nodded that it would be all right. So Magda went happily to write it and learn it by heart.

“Kind of nervy, if you ask me, of that little Jew girl to horn in on our celebration,” said Betty.

“Who asked her to come to America, anyhow?” said another.

“I thought Thanksgiving was for Americans!” said another.

Magda, listening hard, caught the word “Americans,” and her face lighted up. It wouldn’t be long now, she thought, before she could understand them.

No, no, they weren’t specially bad children, no more than you or I—they had heard older people talking like that—and they gabbled along, thoughtlessly, the way we are all apt to repeat what we hear, without considering whether it is right or not.

On Thanksgiving Day a lot of those grownups whose talk Betty and her gang had been repeating had come, as they always did, to the “exercises.” They sat in rows in the assembly room, listening to the singing and acting of the children and saying, “the first graders are too darling,” and “how time flies,” and “can you believe it that Betty is up to my shoulder now? Seems like last week she was in the kindergarten.”

The tall principal stood at one side of the platform and read off the different numbers from a list. By and by he said, “We shall now hear a prayer written by Magda Bensheim and spoken by her. Madga has been in this country only five weeks and in our school only three.”

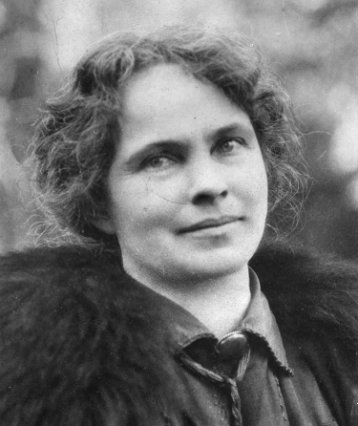

Magda came out to the middle of the platform, a bright, striped apron over her thick woolen dress, her braids tied with red ribbons. Her heart was beating fast. Her face was shining and solemn.

She put her hands together and lifted them up over her head and said to God, “Oh, thank you, thank you, dear God, for letting me come to America and nowhere else, when Grandfather and I were driven from our home. I learn out of my history book that Americans all came to this country just how Grandfather and I come, because Europe treat them wrong and bad. Every year they gather like this—to remember their brave grandfathers who come here so long ago and stay on, although they had such hard times.

“American hearts are so faithful and true that they forget never how they were all refugees, too, and must thankful be that from refugees they come to be American citizens. So thanks to you, dear, dear God, for letting Grandfather and me come to live in a country where they have this beautiful once-a-year Thanksgiving, for having come afraid from Europe to be here free and safe. I, too, feel the same beautiful thank-you-God that all Americans say here today.”

Magda did not know what is usually said in English at the end of a prayer so did not say anything when she finished, just walked away back where the other girls of her class were. But the principal said it for her—after he had given his nose a good blow and wiped his eyes. He looked out over the people in the audience and said in a loud, strong voice, “Amen! I say Amen, and so does everybody here, I know.”

And then—it was sort of queer to applaud a prayer—they all began to clap their hands loudly.

Back in the seventh-grade room the teacher was saying, “Well, children, that’s all. See you next Monday. Don’t eat too much turkey.” But Betty jumped up and said, “Wait a minute, Miss Turner. Wait a minute, kids. I want to lead a cheer. All ready?

“Three cheers for Magda!

“Hip! Hip!” She leaned ’way over to one side and touched the floor, and they all shouted, “Hurrah!”

She bent back to the other side. “Hurrah!” they shouted.

She jumped straight up till both feet were off the ground and clapped her hands over her head, and “Hurrah!” they all shouted.

The wonderful moment had come. The curtain that had shut Magda off from her schoolmates had gone. “Oh! Ach!” she cried, her eyes wide. “Why, I understand every word. Yes, now I can understand American!”

Return to The Meaning of Thanksgiving Day.

Post a Comment