As soon as the Civil War ended, a joint resolution by the US Congress ordered the War Department to create an official history of the army’s actions during the war. Published between 1881 and 1901—and comprising 128 books organized into 70 volumes—the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion marked the unofficial beginning of the US Army Center of Military History (CMH), which was formally commissioned in 1943. Since then the Center has expanded its mission beyond the creation of official military histories and now provides support for military education and manages the army’s museum system. Today, CMH oversees a system of 59 army museums and 176 other holdings, representing approximately 500,000 artifacts and more than 15,000 works of military art.

The origins of the US Army’s art collection date back to World War I, when the Corps of Engineers commissioned eight artists to document the activities of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe. At the end of the war, most of the team’s artwork went to the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of American History in Washington, DC.

When World War II began, the Corps of Engineers revived the army art program, establishing the War Art Unit in late 1942. The War Art Advisory Committee, which included prominent artists such as George Biddle and writer John Steinbeck, commissioned 42 artists to serve in the unit: 23 artists already serving in the military and 19 civilians. Biddle described the unit’s mission in a March 1943 memorandum:

Any subject is in order, if as artists you feel that it is part of War; battle scenes and the front line; battle landscapes; the wounded, the dying and the dead; prisoners of war; field hospitals and base hospitals; wrecked habitations and bombing scenes; character sketches of our own troops, of prisoners, of the natives of the country you visit . . . the nobility, courage, cowardice, cruelty, boredom of war; all this should form part of a well-rounded picture. Try to omit nothing; duplicate to your heart’s content. Express if you can—realistically or symbolically—the essence and spirit of war. . . . We believe that our Army Command is giving you an opportunity to bring back a record of great value to our country. Our committee wants to assist you to that end.1

The artists were sent to the South Pacific and other theaters around the globe. These efforts contributed to the creation of over 2,000 works of art during World War II.

Since World War II, professional artists have been assigned to document the Korean and Vietnam Wars and Operations Desert Storm and Desert Shield. In generating on-the-spot paintings or preliminary sketches, military artists have been exposed to the same challenging conditions and dangers faced by soldiers. Most recently, staff artists deployed with the army have documented the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Center of Military History currently holds nearly 16,000 works of art, which represent the efforts of more than 1,300 soldier-artists in the army’s art program, as well as many other artists who have donated their works. Currently under construction in Fort Belvoir, Virginia, the new National Museum of the United States Army will include works of art from the collection in its exhibits. The museum, designed to “celebrate and honor the Army and its extensive part in the building of America,” is scheduled to open in 2015.

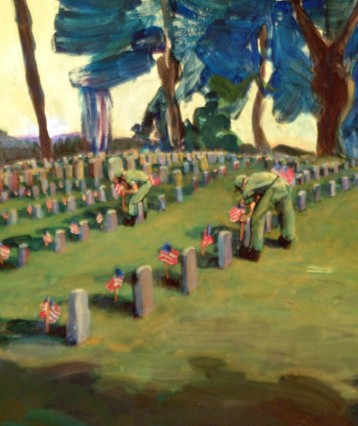

This 1976 painting by artist Ellen White belongs to the CMH’s collection of images of Arlington National Cemetery. Two soldiers take part in a Memorial Day tradition, known as “flags in,” placing small American flags one foot in front and centered before each grave marker. This tradition has been conducted annually at the cemetery since 1948 when the Third US Infantry (“The Old Guard”) was designated as the army’s official ceremonial unit.

What is the overall mood of the painting? Look carefully at the details of the soldiers, their deeds, and the positions of the flags: How do these details contribute to the overall effect? Why does White draw our attention to the trees among the grave markers? What does the yellow sky in the background add to the feeling? How well does this image capture the spirit and meaning of Memorial Day?

Post a Comment