How To Use This Discussion Guide

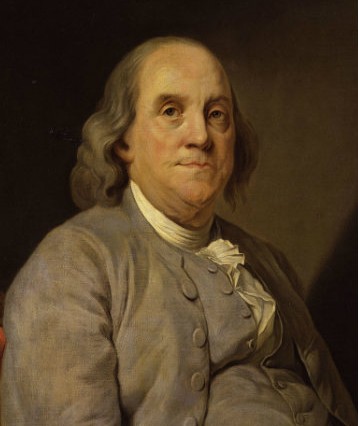

Materials Included | Begin by reading Benjamin Franklin’s “Project for Moral Perfection” on our site or in your copy of What So Proudly We Hail.

Materials for this guide include background information about the author and discussion questions to enhance your understanding and stimulate conversation about the story. In addition, the guide includes a series of short video discussions about the story, conducted by Wilfred McClay (University of Tennessee–Chattanooga) with the editors of the anthology. These seminars help capture the experience of high-level discourse as participants interact and elicit meaning from a classic American text. These videos are meant to raise additional questions and augment discussion, not replace it.

Learning Objectives | Students will be able to:

- Consider the virtues of self-command and self-respect and what it means to be self-made;

- Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it;

- Cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text;

- Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development

- Summarize the key supporting details and ideas;

- Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text;

- Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone; and

- Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning and the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

Common Core State Standards Addressed | Literacy in History/Social Studies

- RH.9-10.1, RH.9-10.2, RH.9-10.5, RH.11-12.1, RH.11-12.2, RH.11-12.4, RH.11-12.5

English Language Arts:

- RL.9-10.1, RL.9-10.2, RL.9-10.4, RL.11-12.1, RL.11-12.4

Writing Prompts | Based on Common Core Standards in English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies:

- Is virtue its own reward? After reading Franklin’s “Project for Moral Perfection,” write an essay that defines “virtue” and explains the reasons Franklin gives for practicing virtue. Support your discussion with evidence from the text. (Informational or Explanatory/Definition; Task 12)

- Is it possible to be a good citizen in our self-governing nation without first governing oneself? Can one be a “free human being” without self-command? After reading Franklin’s “Project for Moral Perfection,” write a position paper that addresses the question and support your position with evidence from the text. Be sure to acknowledge competing views. Give examples from past or current events or issues to illustrate and clarify your position. (Argumentation/Analysis; Task 2)

- Has Franklin provided a necessary and sufficient moral framework for educating free, self-governing citizens in a modern commercial society? What virtues would you add, delete, or replace, for citizens of 21st century America? What about courage and self-sacrifice or generosity or reverence? What about compassion and public spiritedness? Is self-command sufficient to induce the willingness to serve one’s neighbors or one’s community and country? After reading Franklin’s “Project for Moral Perfection,” write an essay that discusses the thirteen virtues Franklin wrote about and attempted to cultivate in his own life, and evaluate the sufficiency of these virtues to create a sustainable civic culture. (Argumentation/Evaluation; Task 6)

Post a Comment