Introduction

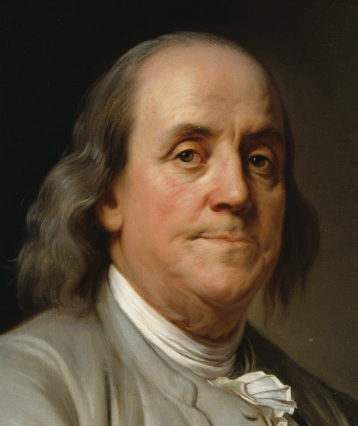

Arguably more than other American Founders, Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) gave serious attention to the education and character needed for citizens of the newly founded Republic. Keenly aware of the importance of self-command for both individual flourishing and effective social activity, Franklin understood why the turbulent human soul must first be tamed if we are to become reasonable, free, and responsible social beings and citizens. Many of his writings, from the Dogood Papers (1722) to his Autobiography (from which this selection, written in 1784, is taken), sought to promote these goals.

The centerpiece of the Autobiography is his “bold and arduous Project” to reconstitute himself by arriving at moral perfection. By this device, Franklin depicts a middle-class citizen of an individualistic, democratic, and commercial society, which places health, wealth, self-esteem, and public reputation within reach of any American who would imitate Franklin’s cultivation of useful self-command. For Franklin, the principle of American democracy is freedom—freedom from inherited modes and orders, freedom for felicity and engagement in public life—and moral virtue is its critical means.

When you read the list of enumerated virtues, along with their explanations and commentary, ask yourself what a person who embodied these virtues would be like. Would these virtues produce both a good human being and a good citizen? How does Franklin’s conception of the virtues compare to more traditional religious conceptions? What virtues are essential for citizens of a modern, commercial republic? What virtues would you add to, or subtract from, Franklin’s list? Should we each undertake something like Franklin’s project of moral self-improvement?

It was about this time [circa 1728] that I conceiv’d the bold and arduous Project of arriving at moral Perfection. I wish’d to live without committing any Fault at any time; I would conquer all that either Natural Inclination, Custom, or Company might lead me into. As I knew, or thought I knew, what was right and wrong, I did not see why I might not always do the one and avoid the other. But I soon found I had undertaken a Task of more Difficulty than I had imagined: While my Care was employ’d in guarding against one Fault, I was often surpriz’d by another. Habit took the Advantage of Inattention. Inclination was sometimes too strong for Reason. I concluded at length, that the mere speculative Conviction that it was our Interest to be compleatly virtuous, was not sufficient to prevent our Slipping, and that the contrary Habits must be broken and good Ones acquired and established, before we can have any Dependance on a steady uniform Rectitude of Conduct. For this purpose I therefore contriv’d the following Method.—

In the various Enumerations of the moral Virtues I had met with in my Reading, I found the Catalogue more or less numerous, as different Writers included more or fewer Ideas under the same Name. Temperance, for Example, was by some confin’d to Eating & Drinking, while by others it was extended to mean the moderating every other Pleasure, Appetite, Inclination or Passion, bodily or mental, even to our Avarice & Ambition. I propos’d to myself, for the sake of Clearness, to use rather more Names with fewer Ideas annex’d to each, than a few Names with more Ideas; and I included under Thirteen Names of Virtues all that at that time occurr’d to me as necessary or desirable, and annex’d to each a short Precept, which fully express’d the Extent I gave to its Meaning.—

These Names of Virtues with their Precepts were

1. TEMPERANCE.

Eat not to Dulness.

Drink not to Elevation.

2. SILENCE.

Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself. Avoid trifling Conversation.

3. ORDER.

Let all your Things have their Places. Let each Part of your Business have its Time.

4. RESOLUTION.

Resolve to perform what you ought. Perform without fail what you resolve.

5. FRUGALITY.

Make no Expence but to do good to others or yourself: i.e. Waste nothing.

6. INDUSTRY.

Lose no Time.—Be always employ’d in something useful.—Cut off all unnecessary Actions.—

7. SINCERITY.

Use no hurtful Deceit.

Think innocently and justly; and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

8. JUSTICE.

Wrong none, by doing Injuries or omitting the Benefits that are your Duty.

9. MODERATION.

Avoid Extreams. Forbear resenting Injuries so much as you think they deserve.

10. CLEANLINESS.

Tolerate no Uncleanness in Body, Cloaths or Habitation.—

11. TRANQUILITY.

Be not disturbed at Trifles, or at Accidents common or unavoidable.

12. CHASTITY.

Rarely use Venery but for Health or Offspring; Never to Dulness, Weakness, or the Injury of your own or another’s Peace or Reputation.—

13. HUMILITY.

Imitate Jesus and Socrates.—

My Intention being to acquire the Habitude of all these Virtues, I judg’d it would be well not to distract my Attention by attempting the whole at once, but to fix it on one of them at a time, and when I should be Master of that, then to proceed to another, and so on till I should have gone thro’ the thirteen. And as the previous Acquisition of some might facilitate the Acquisition of certain others, I arrang’d them with that View as they stand above. Temperance first, as it tends to procure that Coolness & Clearness of Head, which is so necessary where constant Vigilance was to be kept up, and Guard maintained, against the unremitting Attraction of ancient Habits, and the Force of perpetual Temptations. This being acquir’d & establish’d, Silence would be more easy, and my Desire being to gain Knowledge at the same time that I improv’d in Virtue, and considering that in Conversation it was obtain’d rather by the Use of the Ears than of the Tongue, & therefore wishing to break a Habit I was getting into of Prattling, Punning & Joking, which only made me acceptable to trifling Company, I gave Silence the second Place. This, and the next, Order, I expected would allow me more Time for attending to my Project and my Studies; Resolution, once become habitual, would keep me firm in my Endeavours to obtain all the subsequent Virtues; Frugality & Industry, by freeing me from my remaining Debt, & producing Affluence & Independance, would make more easy the Practice of Sincerity and Justice, &c. &c. Conceiving then that agreeable to the Advice of Pythagoras in his Golden Verses, daily Examination would be necessary, I contriv’d the following Method for conducting that Examination.

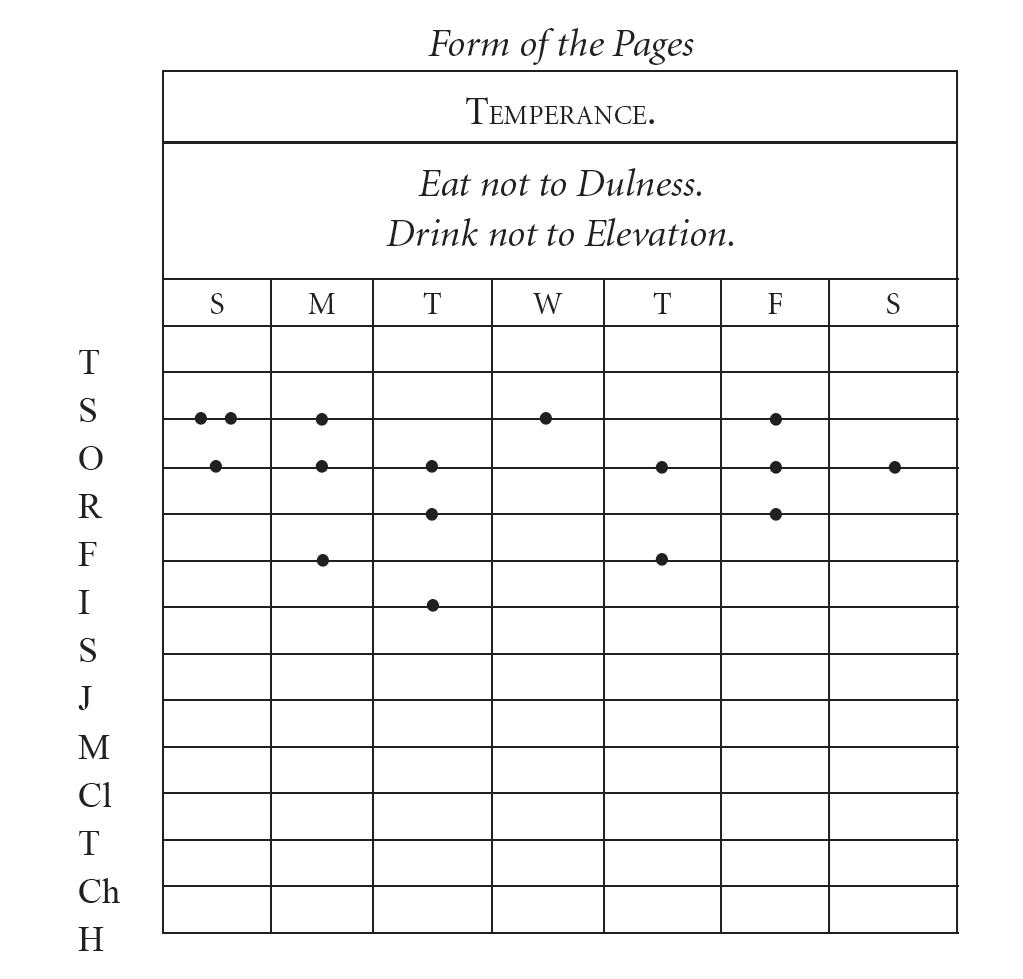

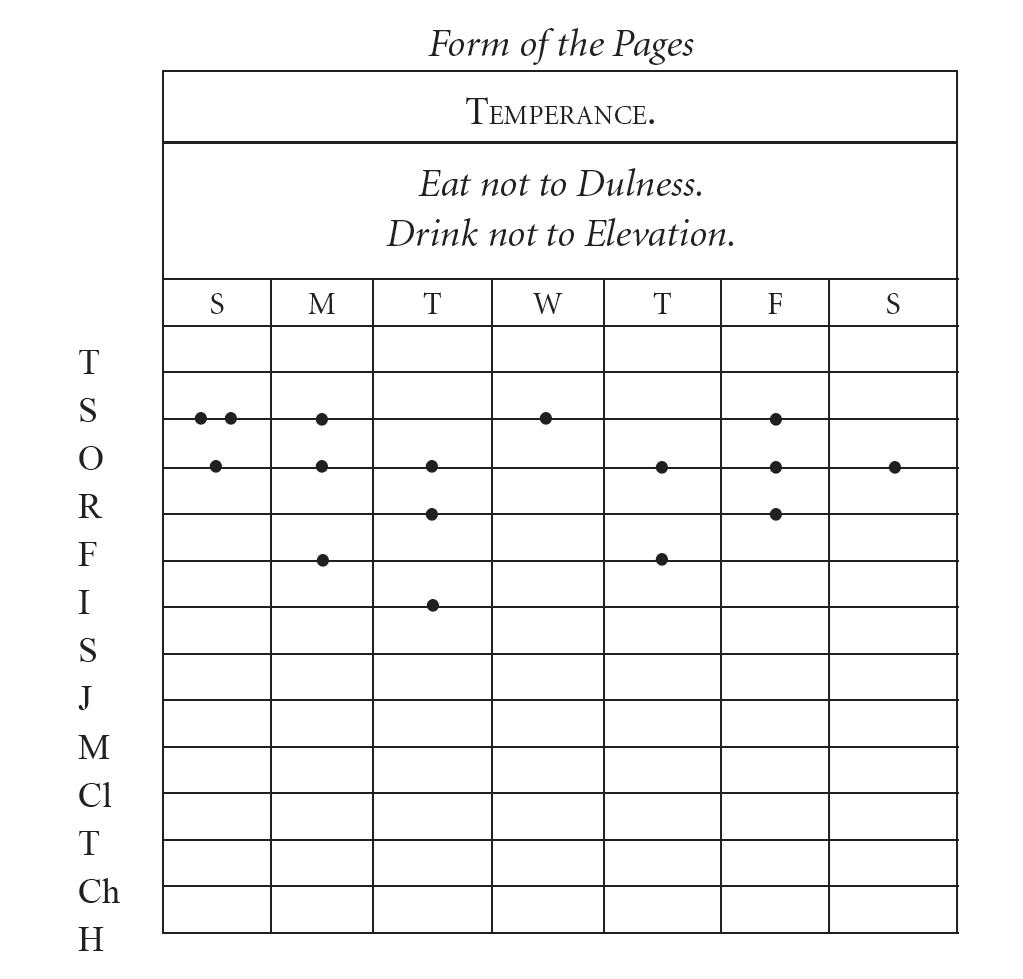

I made a little Book in which I allotted a Page for each of the Virtues. I rul’d each Page with red Ink so as to have seven Columns, one for each Day of the Week, marking each Column with a Letter for the Day. I cross’d these Columns with thirteen red Lines, marking the Beginning of each Line with the first Letter of one of the Virtues, on which Line & in its proper Column I might mark by a little black Spot every Fault I found upon Examination, to have been committed respecting that Virtue upon that Day.

I determined to give a Week’s strict Attention to each of the Virtues successively. Thus in the first Week my great Guard was to avoid every the least Offence against Temperance, leaving the other Virtues to their ordinary Chance, only marking every Evening the Faults of the Day. Thus if in the first Week I could keep my first Line marked T clear of Spots, I suppos’d the Habit of that Virtue so much strengthen’d and its opposite weaken’d, that I might venture extending my Attention to include the next, and for the following Week keep both Lines clear of Spots. Proceeding thus to the last, I could go thro’ a Course compleat in Thirteen Weeks, and four Courses in a Year.—And like him who having a Garden to weed, does not attempt to eradicate all the bad Herbs at once, which would exceed his Reach and his Strength, but works on one of the Beds at a time, & having accomplish’d the first proceeds to a second; so I should have, (I hoped) the encouraging Pleasure of seeing on my Pages the Progress I made in Virtue, by clearing successively my Lines of their Spots, till in the End by a Number of Courses, I should be happy in viewing a clean Book after a thirteen Weeks daily Examination. . . .

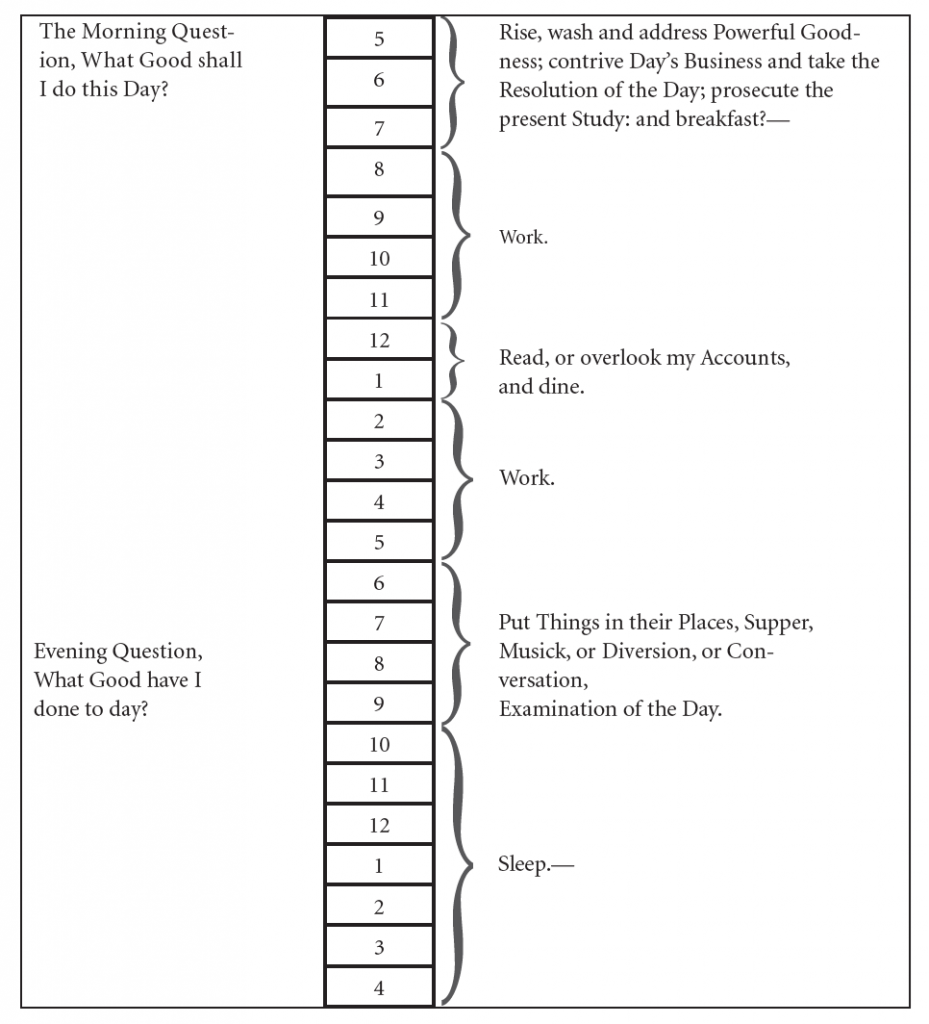

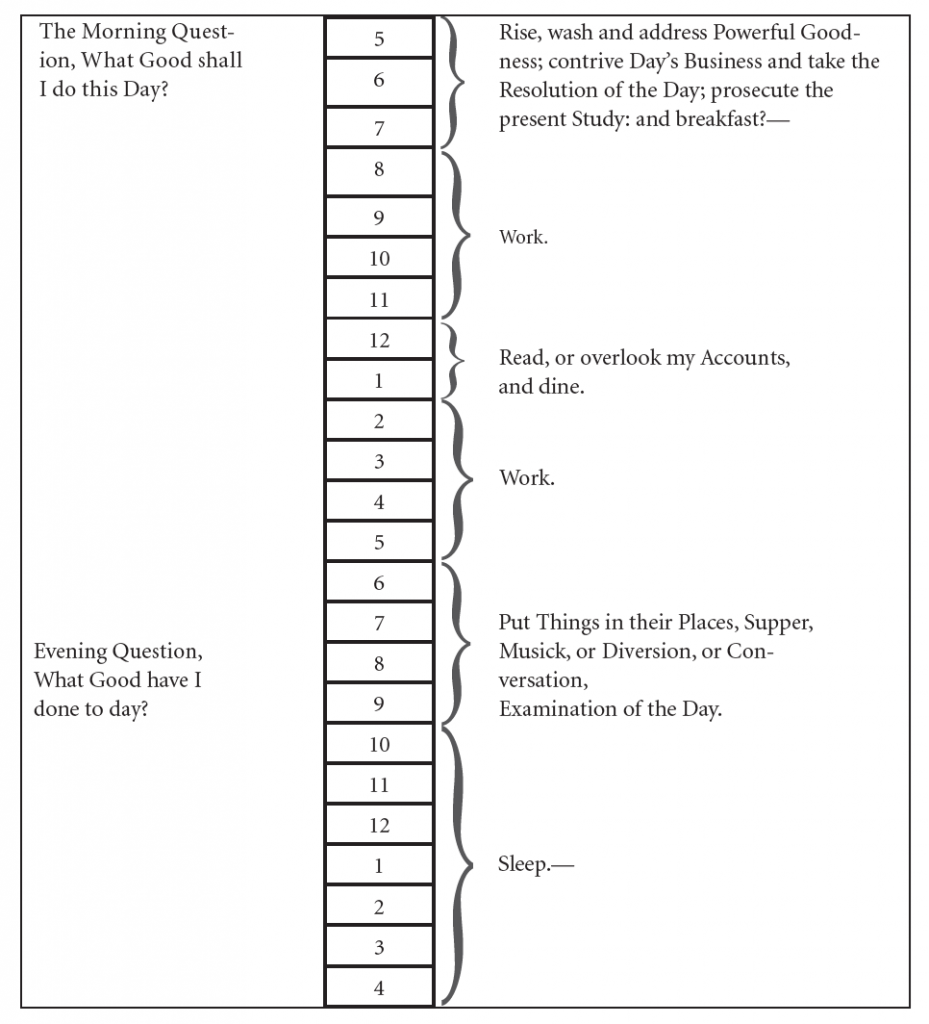

The Precept of Order requiring that every Part of my Business should have its allotted Time, one Page in my little Book contain’d the following Scheme of Employment for the Twenty-four Hours of a natural Day,

I determined to give a Week’s strict Attention to each of the Virtues successively. Thus in the first Week my great Guard was to avoid every the least Offence against Temperance, leaving the other Virtues to their ordinary Chance, only marking every Evening the Faults of the Day. Thus if in the first Week I could keep my first Line marked T clear of Spots, I suppos’d the Habit of that Virtue so much strengthen’d and its opposite weaken’d, that I might venture extending my Attention to include the next, and for the following Week keep both Lines clear of Spots. Proceeding thus to the last, I could go thro’ a Course compleat in Thirteen Weeks, and four Courses in a Year.—And like him who having a Garden to weed, does not attempt to eradicate all the bad Herbs at once, which would exceed his Reach and his Strength, but works on one of the Beds at a time, & having accomplish’d the first proceeds to a second; so I should have, (I hoped) the encouraging Pleasure of seeing on my Pages the Progress I made in Virtue, by clearing successively my Lines of their Spots, till in the End by a Number of Courses, I should be happy in viewing a clean Book after a thirteen Weeks daily Examination. . . .

The Precept of Order requiring that every Part of my Business should have its allotted Time, one Page in my little Book contain’d the following Scheme of Employment for the Twenty-four Hours of a natural Day,

I enter’d upon the Execution of this Plan for Self Examination, and continu’d it with occasional Intermissions for some time. I was surpriz’d to find myself so much fuller of Faults than I had imagined, but I had the Satisfaction of seeing them diminish. To avoid the Trouble of renewing now & then my little Book, which by scraping out the Marks on the Paper of old Faults to make room for new Ones in a new Course, became full of Holes: I transferr’d my Tables & Precepts to the Ivory Leaves of a Memorandum Book, on which the Lines were drawn with red Ink that made a durable Stain, and on those Lines I mark’d my Faults with a black Lead Pencil, which Marks I could easily wipe out with a wet Sponge. After a while I went thro’ one Course only in a Year, and afterwards only one in several Years; till at length I omitted them entirely, being employ’d in Voyages & Business abroad with a Multiplicity of Affairs, that interfered. But I always carried my little Book with me. My Scheme of order, gave me the most Trouble, and I found, that tho’ it might be practicable where a Man’s Business was such as to leave him the Disposition of his Time, that of a Journey-man Printer for instance, it was not possible to be exactly observ’d by a Master, who must mix with the World, and often receive People of Business at their own Hours.—Order too, with regard to Places for Things, Papers, &c. I found extreamly difficult to acquire. I had not been early accustomed to it, & having an exceeding good Memory, I was not so sensible of the Inconvenience attending Want of Method. This Article therefore cost me so much painful Attention & my Faults in it vex’d me so much, and I made so little Progress in Amendment, & had such frequent Relapses, that I was almost ready to give up the Attempt, and content my self with a faulty Character in that respect. Like the Man who in buying an Ax of a Smith my neighbour, desired to have the whole of its Surface as bright as the Edge; the Smith consented to grind it bright for him if he would turn the Wheel. He turn’d while the Smith press’d the broad Face of the Ax hard & heavily on the Stone, which made the Turning of it very fatiguing. The Man came every now & then from the Wheel to see how the Work went on; and at length would take his Ax as it was without farther Grinding. No, says the Smith, Turn on, turn on; we shall have it bright by and by; as yet ’tis only speckled. Yes, says the Man; but—I think I like a speckled Ax best.—And I believe this may have been the Case with many who having for want of some such Means as I employ’d found the Difficulty of obtaining good, & breaking bad Habits, in other Points of Vice & Virtue, have given up the Struggle, & concluded that a speckled Ax was best. For something that pretended to be Reason was every now and then suggesting to me, that such extream Nicety as I exacted of my self might be a kind of Foppery in Morals, which if it were known would make me ridiculous; that a perfect Character might be attended with the Inconvenience of being envied and hated; and that a benevolent Man should allow a few Faults in himself, to keep his Friends in Countenance. In Truth I found myself incorrigible with respect to Order; and now I am grown old, and my Memory bad, I feel very sensibly the want of it. But on the whole, tho’ I never arrived at the Perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far short of it, yet I was by the Endeavour a better and happier Man than I otherwise should have been, if I had not attempted it; As those who aim at perfect Writing by imitating the engraved Copies, tho’ they never reach the wish’d for Excellence of those Copies, their Hand is mended by the Endeavour, and is tolerable while it continues fair & legible.—

And it may be well my Posterity should be informed, that to this little Artifice, with the Blessing of God, their Ancestor ow’d the constant Felicity of his Life down to his 79th Year in which this is written. What Reverses may attend the Remainder is in the Hand of Providence: But if they arrive the Reflection on past Happiness enjoy’d ought to help his bearing them with more Resignation. To Temperance he ascribes his long-continu’d Health, & what is still left to him of a good Constitution. To Industry and Frugality the early Easiness of his Circumstances, & Acquisition of his Fortune, with all that Knowledge which enabled him to be an useful Citizen, and obtain’d for him some Degree of Reputation among the Learned. To Sincerity & Justice the Confidence of his Country, and the honourable Employs it conferr’d upon him. And to the joint Influence of the whole Mass of the Virtues, even in the imperfect State he was able to acquire them, all that Evenness of Temper, & that Chearfulness in Conversation which makes his Company still sought for, & agreable even to his younger Acquaintance. I hope therefore that some of my Descendants may follow the Example & reap the Benefit.— . . .

My List of Virtues contain’d at first but twelve: But a Quaker Friend having kindly inform’d me that I was generally thought proud; that my Pride show’d itself frequently in Conversation; that I was not content with being in the right when discussing any Point, but was overbearing & rather insolent; of which he convinc’d me by mentioning several Instances;—I determined endeavouring to cure myself if I could of this Vice or Folly among the rest, and I added Humility to my List, giving an extensive Meaning to the Word.—I cannot boast of much Success in acquiring the Reality of this Virtue; but I had a good deal with regard to the Appearance of it.—I made it a Rule to forbear all direct Contradiction to the Sentiments of others, and all positive Assertion of my own. I even forbid myself agreable to the old Laws of our Junto, the Use of every Word or Expression in the Language that imported a fix’d Opinion; such as certainly, undoubtedly, &c. and I adopted instead of them, I conceive, I apprehend, or I imagine a thing to be so or so, or it so appears to me at present.—When another asserted something that I thought an Error, I deny’d my self the Pleasure of contradicting him abruptly, and of showing immediately some Absurdity in his Proposition; and in answering I began by observing that in certain Cases or Circumstances his Opinion would be right, but that in the present case there appear’d or seem’d to me some Difference, &c. I soon found the Advantage of this change in my Manners. The Conversations I engag’d in went on more pleasantly. The modest way in which I propos’d my Opinions, procur’d them a readier Reception and less Contradiction; I had less Mortification when I was found to be in the wrong, and I more easily prevail’d with others to give up their Mistakes & join with me when I happen’d to be in the right. And this mode, which I at first put on, with some violence to natural Inclination, became at length so easy & so habitual to me, that perhaps for these Fifty Years past no one has ever heard a dogmatical Expression escape me. And to this Habit (after my Character of Integrity) I think it principally owing, that I had early so much Weight with my Fellow Citizens, when I proposed new Institutions, or Alterations in the old; and so much Influence in public Councils when I became a Member. For I was but a bad Speaker, never eloquent, subject to much Hesitation in my choice of Words, hardly correct in Language, and yet I generally carried my Points.—

In reality there is perhaps no one of our natural Passions so hard to subdue as Pride. Disguise it, struggle with it, beat it down, stifle it, mortify it as much as one pleases, it is still alive, and will every now and then peep out and show itself. You will see it perhaps often in this History. For even if I could conceive that I had compleatly overcome it, I should probably be proud of my Humility.

I enter’d upon the Execution of this Plan for Self Examination, and continu’d it with occasional Intermissions for some time. I was surpriz’d to find myself so much fuller of Faults than I had imagined, but I had the Satisfaction of seeing them diminish. To avoid the Trouble of renewing now & then my little Book, which by scraping out the Marks on the Paper of old Faults to make room for new Ones in a new Course, became full of Holes: I transferr’d my Tables & Precepts to the Ivory Leaves of a Memorandum Book, on which the Lines were drawn with red Ink that made a durable Stain, and on those Lines I mark’d my Faults with a black Lead Pencil, which Marks I could easily wipe out with a wet Sponge. After a while I went thro’ one Course only in a Year, and afterwards only one in several Years; till at length I omitted them entirely, being employ’d in Voyages & Business abroad with a Multiplicity of Affairs, that interfered. But I always carried my little Book with me. My Scheme of order, gave me the most Trouble, and I found, that tho’ it might be practicable where a Man’s Business was such as to leave him the Disposition of his Time, that of a Journey-man Printer for instance, it was not possible to be exactly observ’d by a Master, who must mix with the World, and often receive People of Business at their own Hours.—Order too, with regard to Places for Things, Papers, &c. I found extreamly difficult to acquire. I had not been early accustomed to it, & having an exceeding good Memory, I was not so sensible of the Inconvenience attending Want of Method. This Article therefore cost me so much painful Attention & my Faults in it vex’d me so much, and I made so little Progress in Amendment, & had such frequent Relapses, that I was almost ready to give up the Attempt, and content my self with a faulty Character in that respect. Like the Man who in buying an Ax of a Smith my neighbour, desired to have the whole of its Surface as bright as the Edge; the Smith consented to grind it bright for him if he would turn the Wheel. He turn’d while the Smith press’d the broad Face of the Ax hard & heavily on the Stone, which made the Turning of it very fatiguing. The Man came every now & then from the Wheel to see how the Work went on; and at length would take his Ax as it was without farther Grinding. No, says the Smith, Turn on, turn on; we shall have it bright by and by; as yet ’tis only speckled. Yes, says the Man; but—I think I like a speckled Ax best.—And I believe this may have been the Case with many who having for want of some such Means as I employ’d found the Difficulty of obtaining good, & breaking bad Habits, in other Points of Vice & Virtue, have given up the Struggle, & concluded that a speckled Ax was best. For something that pretended to be Reason was every now and then suggesting to me, that such extream Nicety as I exacted of my self might be a kind of Foppery in Morals, which if it were known would make me ridiculous; that a perfect Character might be attended with the Inconvenience of being envied and hated; and that a benevolent Man should allow a few Faults in himself, to keep his Friends in Countenance. In Truth I found myself incorrigible with respect to Order; and now I am grown old, and my Memory bad, I feel very sensibly the want of it. But on the whole, tho’ I never arrived at the Perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far short of it, yet I was by the Endeavour a better and happier Man than I otherwise should have been, if I had not attempted it; As those who aim at perfect Writing by imitating the engraved Copies, tho’ they never reach the wish’d for Excellence of those Copies, their Hand is mended by the Endeavour, and is tolerable while it continues fair & legible.—

And it may be well my Posterity should be informed, that to this little Artifice, with the Blessing of God, their Ancestor ow’d the constant Felicity of his Life down to his 79th Year in which this is written. What Reverses may attend the Remainder is in the Hand of Providence: But if they arrive the Reflection on past Happiness enjoy’d ought to help his bearing them with more Resignation. To Temperance he ascribes his long-continu’d Health, & what is still left to him of a good Constitution. To Industry and Frugality the early Easiness of his Circumstances, & Acquisition of his Fortune, with all that Knowledge which enabled him to be an useful Citizen, and obtain’d for him some Degree of Reputation among the Learned. To Sincerity & Justice the Confidence of his Country, and the honourable Employs it conferr’d upon him. And to the joint Influence of the whole Mass of the Virtues, even in the imperfect State he was able to acquire them, all that Evenness of Temper, & that Chearfulness in Conversation which makes his Company still sought for, & agreable even to his younger Acquaintance. I hope therefore that some of my Descendants may follow the Example & reap the Benefit.— . . .

My List of Virtues contain’d at first but twelve: But a Quaker Friend having kindly inform’d me that I was generally thought proud; that my Pride show’d itself frequently in Conversation; that I was not content with being in the right when discussing any Point, but was overbearing & rather insolent; of which he convinc’d me by mentioning several Instances;—I determined endeavouring to cure myself if I could of this Vice or Folly among the rest, and I added Humility to my List, giving an extensive Meaning to the Word.—I cannot boast of much Success in acquiring the Reality of this Virtue; but I had a good deal with regard to the Appearance of it.—I made it a Rule to forbear all direct Contradiction to the Sentiments of others, and all positive Assertion of my own. I even forbid myself agreable to the old Laws of our Junto, the Use of every Word or Expression in the Language that imported a fix’d Opinion; such as certainly, undoubtedly, &c. and I adopted instead of them, I conceive, I apprehend, or I imagine a thing to be so or so, or it so appears to me at present.—When another asserted something that I thought an Error, I deny’d my self the Pleasure of contradicting him abruptly, and of showing immediately some Absurdity in his Proposition; and in answering I began by observing that in certain Cases or Circumstances his Opinion would be right, but that in the present case there appear’d or seem’d to me some Difference, &c. I soon found the Advantage of this change in my Manners. The Conversations I engag’d in went on more pleasantly. The modest way in which I propos’d my Opinions, procur’d them a readier Reception and less Contradiction; I had less Mortification when I was found to be in the wrong, and I more easily prevail’d with others to give up their Mistakes & join with me when I happen’d to be in the right. And this mode, which I at first put on, with some violence to natural Inclination, became at length so easy & so habitual to me, that perhaps for these Fifty Years past no one has ever heard a dogmatical Expression escape me. And to this Habit (after my Character of Integrity) I think it principally owing, that I had early so much Weight with my Fellow Citizens, when I proposed new Institutions, or Alterations in the old; and so much Influence in public Councils when I became a Member. For I was but a bad Speaker, never eloquent, subject to much Hesitation in my choice of Words, hardly correct in Language, and yet I generally carried my Points.—

In reality there is perhaps no one of our natural Passions so hard to subdue as Pride. Disguise it, struggle with it, beat it down, stifle it, mortify it as much as one pleases, it is still alive, and will every now and then peep out and show itself. You will see it perhaps often in this History. For even if I could conceive that I had compleatly overcome it, I should probably be proud of my Humility.

I determined to give a Week’s strict Attention to each of the Virtues successively. Thus in the first Week my great Guard was to avoid every the least Offence against Temperance, leaving the other Virtues to their ordinary Chance, only marking every Evening the Faults of the Day. Thus if in the first Week I could keep my first Line marked T clear of Spots, I suppos’d the Habit of that Virtue so much strengthen’d and its opposite weaken’d, that I might venture extending my Attention to include the next, and for the following Week keep both Lines clear of Spots. Proceeding thus to the last, I could go thro’ a Course compleat in Thirteen Weeks, and four Courses in a Year.—And like him who having a Garden to weed, does not attempt to eradicate all the bad Herbs at once, which would exceed his Reach and his Strength, but works on one of the Beds at a time, & having accomplish’d the first proceeds to a second; so I should have, (I hoped) the encouraging Pleasure of seeing on my Pages the Progress I made in Virtue, by clearing successively my Lines of their Spots, till in the End by a Number of Courses, I should be happy in viewing a clean Book after a thirteen Weeks daily Examination. . . .

The Precept of Order requiring that every Part of my Business should have its allotted Time, one Page in my little Book contain’d the following Scheme of Employment for the Twenty-four Hours of a natural Day,

I determined to give a Week’s strict Attention to each of the Virtues successively. Thus in the first Week my great Guard was to avoid every the least Offence against Temperance, leaving the other Virtues to their ordinary Chance, only marking every Evening the Faults of the Day. Thus if in the first Week I could keep my first Line marked T clear of Spots, I suppos’d the Habit of that Virtue so much strengthen’d and its opposite weaken’d, that I might venture extending my Attention to include the next, and for the following Week keep both Lines clear of Spots. Proceeding thus to the last, I could go thro’ a Course compleat in Thirteen Weeks, and four Courses in a Year.—And like him who having a Garden to weed, does not attempt to eradicate all the bad Herbs at once, which would exceed his Reach and his Strength, but works on one of the Beds at a time, & having accomplish’d the first proceeds to a second; so I should have, (I hoped) the encouraging Pleasure of seeing on my Pages the Progress I made in Virtue, by clearing successively my Lines of their Spots, till in the End by a Number of Courses, I should be happy in viewing a clean Book after a thirteen Weeks daily Examination. . . .

The Precept of Order requiring that every Part of my Business should have its allotted Time, one Page in my little Book contain’d the following Scheme of Employment for the Twenty-four Hours of a natural Day,

I enter’d upon the Execution of this Plan for Self Examination, and continu’d it with occasional Intermissions for some time. I was surpriz’d to find myself so much fuller of Faults than I had imagined, but I had the Satisfaction of seeing them diminish. To avoid the Trouble of renewing now & then my little Book, which by scraping out the Marks on the Paper of old Faults to make room for new Ones in a new Course, became full of Holes: I transferr’d my Tables & Precepts to the Ivory Leaves of a Memorandum Book, on which the Lines were drawn with red Ink that made a durable Stain, and on those Lines I mark’d my Faults with a black Lead Pencil, which Marks I could easily wipe out with a wet Sponge. After a while I went thro’ one Course only in a Year, and afterwards only one in several Years; till at length I omitted them entirely, being employ’d in Voyages & Business abroad with a Multiplicity of Affairs, that interfered. But I always carried my little Book with me. My Scheme of order, gave me the most Trouble, and I found, that tho’ it might be practicable where a Man’s Business was such as to leave him the Disposition of his Time, that of a Journey-man Printer for instance, it was not possible to be exactly observ’d by a Master, who must mix with the World, and often receive People of Business at their own Hours.—Order too, with regard to Places for Things, Papers, &c. I found extreamly difficult to acquire. I had not been early accustomed to it, & having an exceeding good Memory, I was not so sensible of the Inconvenience attending Want of Method. This Article therefore cost me so much painful Attention & my Faults in it vex’d me so much, and I made so little Progress in Amendment, & had such frequent Relapses, that I was almost ready to give up the Attempt, and content my self with a faulty Character in that respect. Like the Man who in buying an Ax of a Smith my neighbour, desired to have the whole of its Surface as bright as the Edge; the Smith consented to grind it bright for him if he would turn the Wheel. He turn’d while the Smith press’d the broad Face of the Ax hard & heavily on the Stone, which made the Turning of it very fatiguing. The Man came every now & then from the Wheel to see how the Work went on; and at length would take his Ax as it was without farther Grinding. No, says the Smith, Turn on, turn on; we shall have it bright by and by; as yet ’tis only speckled. Yes, says the Man; but—I think I like a speckled Ax best.—And I believe this may have been the Case with many who having for want of some such Means as I employ’d found the Difficulty of obtaining good, & breaking bad Habits, in other Points of Vice & Virtue, have given up the Struggle, & concluded that a speckled Ax was best. For something that pretended to be Reason was every now and then suggesting to me, that such extream Nicety as I exacted of my self might be a kind of Foppery in Morals, which if it were known would make me ridiculous; that a perfect Character might be attended with the Inconvenience of being envied and hated; and that a benevolent Man should allow a few Faults in himself, to keep his Friends in Countenance. In Truth I found myself incorrigible with respect to Order; and now I am grown old, and my Memory bad, I feel very sensibly the want of it. But on the whole, tho’ I never arrived at the Perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far short of it, yet I was by the Endeavour a better and happier Man than I otherwise should have been, if I had not attempted it; As those who aim at perfect Writing by imitating the engraved Copies, tho’ they never reach the wish’d for Excellence of those Copies, their Hand is mended by the Endeavour, and is tolerable while it continues fair & legible.—

And it may be well my Posterity should be informed, that to this little Artifice, with the Blessing of God, their Ancestor ow’d the constant Felicity of his Life down to his 79th Year in which this is written. What Reverses may attend the Remainder is in the Hand of Providence: But if they arrive the Reflection on past Happiness enjoy’d ought to help his bearing them with more Resignation. To Temperance he ascribes his long-continu’d Health, & what is still left to him of a good Constitution. To Industry and Frugality the early Easiness of his Circumstances, & Acquisition of his Fortune, with all that Knowledge which enabled him to be an useful Citizen, and obtain’d for him some Degree of Reputation among the Learned. To Sincerity & Justice the Confidence of his Country, and the honourable Employs it conferr’d upon him. And to the joint Influence of the whole Mass of the Virtues, even in the imperfect State he was able to acquire them, all that Evenness of Temper, & that Chearfulness in Conversation which makes his Company still sought for, & agreable even to his younger Acquaintance. I hope therefore that some of my Descendants may follow the Example & reap the Benefit.— . . .

My List of Virtues contain’d at first but twelve: But a Quaker Friend having kindly inform’d me that I was generally thought proud; that my Pride show’d itself frequently in Conversation; that I was not content with being in the right when discussing any Point, but was overbearing & rather insolent; of which he convinc’d me by mentioning several Instances;—I determined endeavouring to cure myself if I could of this Vice or Folly among the rest, and I added Humility to my List, giving an extensive Meaning to the Word.—I cannot boast of much Success in acquiring the Reality of this Virtue; but I had a good deal with regard to the Appearance of it.—I made it a Rule to forbear all direct Contradiction to the Sentiments of others, and all positive Assertion of my own. I even forbid myself agreable to the old Laws of our Junto, the Use of every Word or Expression in the Language that imported a fix’d Opinion; such as certainly, undoubtedly, &c. and I adopted instead of them, I conceive, I apprehend, or I imagine a thing to be so or so, or it so appears to me at present.—When another asserted something that I thought an Error, I deny’d my self the Pleasure of contradicting him abruptly, and of showing immediately some Absurdity in his Proposition; and in answering I began by observing that in certain Cases or Circumstances his Opinion would be right, but that in the present case there appear’d or seem’d to me some Difference, &c. I soon found the Advantage of this change in my Manners. The Conversations I engag’d in went on more pleasantly. The modest way in which I propos’d my Opinions, procur’d them a readier Reception and less Contradiction; I had less Mortification when I was found to be in the wrong, and I more easily prevail’d with others to give up their Mistakes & join with me when I happen’d to be in the right. And this mode, which I at first put on, with some violence to natural Inclination, became at length so easy & so habitual to me, that perhaps for these Fifty Years past no one has ever heard a dogmatical Expression escape me. And to this Habit (after my Character of Integrity) I think it principally owing, that I had early so much Weight with my Fellow Citizens, when I proposed new Institutions, or Alterations in the old; and so much Influence in public Councils when I became a Member. For I was but a bad Speaker, never eloquent, subject to much Hesitation in my choice of Words, hardly correct in Language, and yet I generally carried my Points.—

In reality there is perhaps no one of our natural Passions so hard to subdue as Pride. Disguise it, struggle with it, beat it down, stifle it, mortify it as much as one pleases, it is still alive, and will every now and then peep out and show itself. You will see it perhaps often in this History. For even if I could conceive that I had compleatly overcome it, I should probably be proud of my Humility.

I enter’d upon the Execution of this Plan for Self Examination, and continu’d it with occasional Intermissions for some time. I was surpriz’d to find myself so much fuller of Faults than I had imagined, but I had the Satisfaction of seeing them diminish. To avoid the Trouble of renewing now & then my little Book, which by scraping out the Marks on the Paper of old Faults to make room for new Ones in a new Course, became full of Holes: I transferr’d my Tables & Precepts to the Ivory Leaves of a Memorandum Book, on which the Lines were drawn with red Ink that made a durable Stain, and on those Lines I mark’d my Faults with a black Lead Pencil, which Marks I could easily wipe out with a wet Sponge. After a while I went thro’ one Course only in a Year, and afterwards only one in several Years; till at length I omitted them entirely, being employ’d in Voyages & Business abroad with a Multiplicity of Affairs, that interfered. But I always carried my little Book with me. My Scheme of order, gave me the most Trouble, and I found, that tho’ it might be practicable where a Man’s Business was such as to leave him the Disposition of his Time, that of a Journey-man Printer for instance, it was not possible to be exactly observ’d by a Master, who must mix with the World, and often receive People of Business at their own Hours.—Order too, with regard to Places for Things, Papers, &c. I found extreamly difficult to acquire. I had not been early accustomed to it, & having an exceeding good Memory, I was not so sensible of the Inconvenience attending Want of Method. This Article therefore cost me so much painful Attention & my Faults in it vex’d me so much, and I made so little Progress in Amendment, & had such frequent Relapses, that I was almost ready to give up the Attempt, and content my self with a faulty Character in that respect. Like the Man who in buying an Ax of a Smith my neighbour, desired to have the whole of its Surface as bright as the Edge; the Smith consented to grind it bright for him if he would turn the Wheel. He turn’d while the Smith press’d the broad Face of the Ax hard & heavily on the Stone, which made the Turning of it very fatiguing. The Man came every now & then from the Wheel to see how the Work went on; and at length would take his Ax as it was without farther Grinding. No, says the Smith, Turn on, turn on; we shall have it bright by and by; as yet ’tis only speckled. Yes, says the Man; but—I think I like a speckled Ax best.—And I believe this may have been the Case with many who having for want of some such Means as I employ’d found the Difficulty of obtaining good, & breaking bad Habits, in other Points of Vice & Virtue, have given up the Struggle, & concluded that a speckled Ax was best. For something that pretended to be Reason was every now and then suggesting to me, that such extream Nicety as I exacted of my self might be a kind of Foppery in Morals, which if it were known would make me ridiculous; that a perfect Character might be attended with the Inconvenience of being envied and hated; and that a benevolent Man should allow a few Faults in himself, to keep his Friends in Countenance. In Truth I found myself incorrigible with respect to Order; and now I am grown old, and my Memory bad, I feel very sensibly the want of it. But on the whole, tho’ I never arrived at the Perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far short of it, yet I was by the Endeavour a better and happier Man than I otherwise should have been, if I had not attempted it; As those who aim at perfect Writing by imitating the engraved Copies, tho’ they never reach the wish’d for Excellence of those Copies, their Hand is mended by the Endeavour, and is tolerable while it continues fair & legible.—

And it may be well my Posterity should be informed, that to this little Artifice, with the Blessing of God, their Ancestor ow’d the constant Felicity of his Life down to his 79th Year in which this is written. What Reverses may attend the Remainder is in the Hand of Providence: But if they arrive the Reflection on past Happiness enjoy’d ought to help his bearing them with more Resignation. To Temperance he ascribes his long-continu’d Health, & what is still left to him of a good Constitution. To Industry and Frugality the early Easiness of his Circumstances, & Acquisition of his Fortune, with all that Knowledge which enabled him to be an useful Citizen, and obtain’d for him some Degree of Reputation among the Learned. To Sincerity & Justice the Confidence of his Country, and the honourable Employs it conferr’d upon him. And to the joint Influence of the whole Mass of the Virtues, even in the imperfect State he was able to acquire them, all that Evenness of Temper, & that Chearfulness in Conversation which makes his Company still sought for, & agreable even to his younger Acquaintance. I hope therefore that some of my Descendants may follow the Example & reap the Benefit.— . . .

My List of Virtues contain’d at first but twelve: But a Quaker Friend having kindly inform’d me that I was generally thought proud; that my Pride show’d itself frequently in Conversation; that I was not content with being in the right when discussing any Point, but was overbearing & rather insolent; of which he convinc’d me by mentioning several Instances;—I determined endeavouring to cure myself if I could of this Vice or Folly among the rest, and I added Humility to my List, giving an extensive Meaning to the Word.—I cannot boast of much Success in acquiring the Reality of this Virtue; but I had a good deal with regard to the Appearance of it.—I made it a Rule to forbear all direct Contradiction to the Sentiments of others, and all positive Assertion of my own. I even forbid myself agreable to the old Laws of our Junto, the Use of every Word or Expression in the Language that imported a fix’d Opinion; such as certainly, undoubtedly, &c. and I adopted instead of them, I conceive, I apprehend, or I imagine a thing to be so or so, or it so appears to me at present.—When another asserted something that I thought an Error, I deny’d my self the Pleasure of contradicting him abruptly, and of showing immediately some Absurdity in his Proposition; and in answering I began by observing that in certain Cases or Circumstances his Opinion would be right, but that in the present case there appear’d or seem’d to me some Difference, &c. I soon found the Advantage of this change in my Manners. The Conversations I engag’d in went on more pleasantly. The modest way in which I propos’d my Opinions, procur’d them a readier Reception and less Contradiction; I had less Mortification when I was found to be in the wrong, and I more easily prevail’d with others to give up their Mistakes & join with me when I happen’d to be in the right. And this mode, which I at first put on, with some violence to natural Inclination, became at length so easy & so habitual to me, that perhaps for these Fifty Years past no one has ever heard a dogmatical Expression escape me. And to this Habit (after my Character of Integrity) I think it principally owing, that I had early so much Weight with my Fellow Citizens, when I proposed new Institutions, or Alterations in the old; and so much Influence in public Councils when I became a Member. For I was but a bad Speaker, never eloquent, subject to much Hesitation in my choice of Words, hardly correct in Language, and yet I generally carried my Points.—

In reality there is perhaps no one of our natural Passions so hard to subdue as Pride. Disguise it, struggle with it, beat it down, stifle it, mortify it as much as one pleases, it is still alive, and will every now and then peep out and show itself. You will see it perhaps often in this History. For even if I could conceive that I had compleatly overcome it, I should probably be proud of my Humility.

Post a Comment