How To Use This Discussion Guide

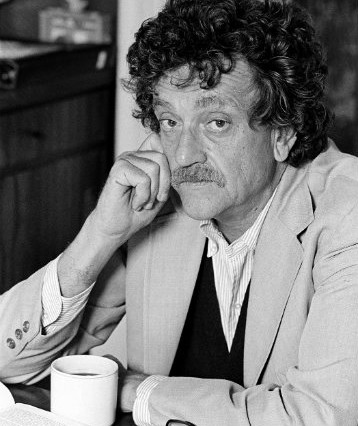

Materials Included | Begin by reading Kurt Vonnegut Jr.’s “Harrison Bergeron” or in your copy of What So Proudly We Hail.

Materials for this guide include background information about the author and discussion questions to enhance your understanding and stimulate conversation about the story. In addition, the guide includes a series of short video discussions about the story, conducted by James W. Ceaser (University of Virginia) with the editors of the anthology. These seminars help capture the experience of high-level discourse as participants interact and elicit meaning from a classic American text. These videos are meant to raise additional questions and augment discussion, not replace it.

Learning Objectives | Students will be able to:

- Examine the difference between equality of outcome and equality of opportunity through reading Kurt Vonnegut Jr.’s “Harrison Bergeron” in relation to the idea of equality presented in the Declaration of Independence;

- Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it;

- Cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text;

- Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development

- Summarize the key supporting details and ideas;

- Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text;

- Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning and the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence; and

- Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

Common Core State Standards Addressed | Literacy in History/Social Studies

- RH.9-10.2, RH.9-10.3, RH.9-10.8, RH.11-12.2, RH.11-12.8, RH.11-12.9

English Language Arts:

- RL.9-10.1, RL.9-10.2, RL.9-10.3, RL.11-12.1, RL.11-12.3, RL.11-12

Writing Prompts | Based on Common Core Standards in English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies:

- What is equality? After reading “Harrison Bergeron” and the Declaration of Independence, write an essay that defines the American principle of equality and explains how the story and the founding document views the term. Support your discussion with evidence from the texts. (Informational or Explanatory/Definition; Task 12)

- What do we owe those of our fellow citizens who are worse off through no fault of their own? After reading the story, write an op-ed that addresses the question and support your position with evidence from the text. (Argumentation/Analysis; Task 2)

- Would you object if society sought equality not by handicapping the gifted but by lifting up the not-gifted, say through genetic engineering or biotechnological enhancement? After reading “Harrison Bergeron,” write an essay that discusses this question and evaluates the pros and cons of “lifting up.” Be sure to support your position with evidence from the text. (Argumentation/Evaluation; Task 6)

Post a Comment