How To Use This Discussion Guide

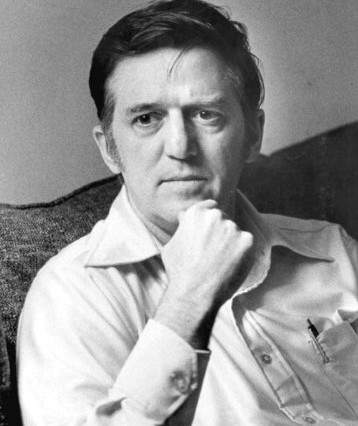

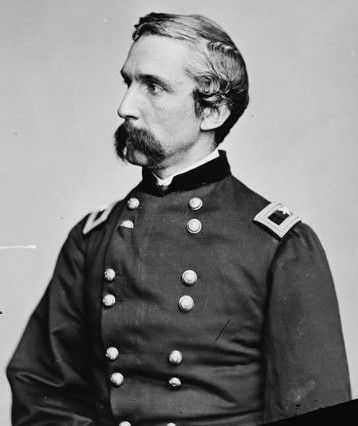

Materials Included | Begin by reading Michael Shaara’s “Chamberlain” on our site or in your copy of What So Proudly We Hail.

Materials for this guide include background information about the author and discussion questions to enhance your understanding and stimulate conversation about the story. In addition, the guide includes a series of short video discussions about the story, conducted by Eliot A. Cohen (Johns Hopkins SAIS) with the editors of the anthology. These seminars help capture the experience of high-level discourse as participants interact and elicit meaning from a classic American text. These videos are meant to raise additional questions and augment discussion, not replace it.

Learning Objectives | Students will be able to:

- Explore the virtue of courage and how it can be cultivated, especially among self-interested citizens oriented toward the pursuit of their own happiness;

- Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it;

- Cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text;

- Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development

- Summarize the key supporting details and ideas;

- Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text;

- Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone;

- Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to one another and the whole; and

- Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

Common Core State Standards Addressed | Literacy in History/Social Studies:

- RH.9-10.1, RH.9-10.2, RH.9-10.6, RH.11-12.1, RH.11-12.2, RH.11-12.4, RH.11-12.6, RH.11-12.8, RH.11-12.9

English Language Arts:

- RL.9-10.1, RL.9-10.2, RL.9-10.4, RL.11-12.1, RL.11-12.3, RL.11-12.4

Writing Prompts | Based on Common Core Standards in English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies:

- The bulk of our attention is directed at Chamberlain’s speech to the men. But Shaara also lets us watch his actions toward and before them from the time they arrive; his manner, tone, and gestures; and the order in which he proceeds. Look carefully at all aspects of his conduct. How do they strike you as a reader? How might they have moved you were you among the mutineers? After reading “Chamberlain,” write a narrative from the perspective of the mutineers. How would you respond to Chamberlain if you were one of the mutineers? (Narrative/Description; Task 27)

- How do you encourage men and women to be courageous? After reading “Chamberlain” and Patton’s “Speech to the Third Army,” write an essay that compares Chamberlain’s and Patton’s understanding of courage and leadership and argues for one mode of leadership over the other. Be sure to support your position with evidence from the texts. (Argumentation/Comparison; Task 4)

- Is there a difference between fighting for your honor and manhood—to avoid being a coward—and fighting for a cause or country? After reading “Chamberlain” and Patton’s “Speech to the Third Army,” write an essay that compares the two different reasons for fighting and argues for one reason over the other. Be sure to support your position with evidence from the texts.(Argumentation/Comparison; Task 4)

Post a Comment