Summary

The basic plot is rather simple: a middling Wall Street lawyer—also the narrator of the story—needing more assistance, hires a new scrivener (copyist) to join his firm. Enter Bartleby. Although initially very productive in his copying, after three days he calmly refuses when asked to help with proofreading or any other office tasks: “I would prefer not to” is his reply, one repeated more than twenty times in the story. The lawyer and his other employees are shocked, but Bartleby holds fast: he prefers not to. Both touched and disconcerted yet choosing not to fire him, the lawyer is strangely drawn into coping with Bartleby and his growing refusals and eccentricities—the theme of the rest of the story.

Bartleby, we learn, is always in the office, either incessantly working or staring out the window at a facing wall. On a chance Sunday visit to the office, the lawyer discovers that Bartleby also lives there. Eventually Bartleby’s refusals extend also to his work as a copyist: he prefers not to do any work, yet he prefers not to quit the office. The lawyer, waffling between pity and indignation, finally asks him—bribes him—to leave, then later commands him to leave his office. But Bartleby prefers not to. Instead, the lawyer moves his office, leaving Bartleby behind.

Another lawyer moves into the building and quickly learns that Bartleby comes with the territory. He complains to the narrator, who disclaims any responsibility for him. The new proprietor has Bartleby arrested for vagrancy, and he is imprisoned in “the Tombs,” officially known as the Halls of Justice (33). There, too, he prefers not to, including “not to eat.” The narrator visits Bartleby but can’t get through to him. On his next visit, the narrator finds Bartleby lying dead, huddled against a wall in the prison yard.

At the very end, in a brief coda, the narrator informs us of a late-arriving rumor to the effect that Bartleby had previously worked as a clerk in an obscure branch of the Post Office known as the Dead Letter Office, sorting through undeliverable mail—mail that would have brought hoped-for news and gifts to people who died with their hopes unfulfilled.

Section Overview

Unlike its basic plot, the story’s meaning and implications are far from simple. So we will proceed slowly, starting with what we learn of the characters and then moving to the heart of the story, the relationship between Bartleby and the lawyer. We conclude this section by attending to the story’s short coda.

A. The Characters

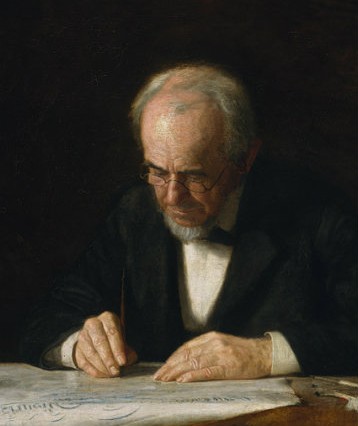

Early in the story, the narrator/lawyer says: “Ere introducing the scrivener [i.e., Bartleby], as he first appeared to me, it is fit I make some mention of myself, my employés, my business, my chambers, and general surroundings; because some such description is indispensable to an adequate understanding of the chief character [Bartleby] about to be presented” (2). Following this lead, and limiting ourselves to the first five pages of the story, look at each in turn:

- The lawyer—what is he like?

- What do you make of his “profound conviction” that the easiest life is the best? Do you share this conviction?

- What does it mean to be considered by others as “an eminently safe man"?

- What does John Jacob Astor (a German-American business and one of America’s first multimillionaires) mean to the lawyer? And what we do learn about him from his mention of Astor?

- Why does the narrator draw attention to the fact that he received but soon lost the office of “Master of Chancery”? (Note: A chancery court has jurisdiction over matters of equity, including trusts, land law, the administration of the estates of lunatics, and the guardianship of infants.)

- Why doesn’t the narrator tell us his name?

- The employés (i.e., the two scriveners, Turkey and Nippers and his office boy, Ginger Nut)—what are they like?

- From the story, what do you understand is the work of a scrivener? How does it differ from the work of ancient scribes, who copied holy books?

- What do the attitudes and ways of his scriveners tell us about the lawyer as an employer? As a human being?

- The business—what sort of law does the lawyer practice?

- Why does he refer to it as a “snug business”?

- The chambers and general surroundings—what are they like?

- Focusing now on the “advent” of Bartleby (3) describe:

- Bartleby—what is he like?

- Describe the work quarters he has been given.

- What would it be like to work in such quarters?

WATCH: What is the lawyer like? What are his employees like?

B. Bartleby’s Conduct with the Lawyer

“It is, of course,” the lawyer/narrator explains, “an indispensable part of a scrivener’s business to verify the accuracy of his copy, word by word” (8). And, as we soon learn, “common usage and common sense” (10) require copyists to assist, as well, in the proofreading of others’ copy and to help out with other office tasks. But when Bartleby is asked, on the third day of his employment, to help proofread a document, he says, “I would prefer not to.” And, after twenty-plus other requests, Bartleby makes twenty-plus similar replies. We watch as Bartleby’s responses—almost all negative preferences, stated mildly but firmly and without anger or impatience—gradually extend from preferring not to proofread, then to copying anything, then to doing any tasks or activities whatsoever, even eating. He becomes more and more passive, gradually withdrawing more and more into his “hermitage,” his “dead-wall reveries,” and himself. To the lawyer, he gradually appears more and more like a “ghost,” an “apparition,” and a “cadaver.”

- What do you think of Bartleby’s responses to the lawyer?

- What do you make of his peculiarities?

- What does his appearance suggest about his attitude toward other people? Toward work or activity, in general? Toward the world?

- Why does Bartleby “prefer not to” perform more and more actions throughout the story? Does this say more about the nature of the work or more about the state of his soul?

- Is there a difference between stating one’s preferences (negatively or positively) and imposing one’s will? Does “I would prefer not to” differ from “I will not”?

- Is it possible to say what motivates Bartleby? Or is he a mystery beyond comprehension?

- Is Bartleby unique? Or are there other “Bartlebys” in the world? In history? In literature?, who—from whatever cause—become passive and passionless beings with largely negative preferences?

WATCH: How does the lawyer respond to Bartleby? Does he understand Bartleby?

C. The Lawyer’s Conduct toward Bartleby

In responding to Bartleby, the lawyer “rall[ies his] stunned faculties” (8) but becomes annoyed; he is repeatedly “disarmed” and “unmanned” (16) by him but also “in a wonderful manner touched and disconcerted” (10); he is full of pity but also repulsion; he is “thunderstruck” (25) by Bartleby but recognizes his “wondrous ascendancy” (25) over him.

After discovering that Bartleby lives in his office, he feels “stinging” and “fraternal” melancholy—we are both “sons of Adam,” he realizes (17)—but he instantly rejects it as “sad fancyings.” Indeed, in several places, he describes his responses, using Biblical (e.g., “a pillar of salt,” 10), generally religious (e.g., 16), and specifically Christian references (e.g., 26).

But despite his mixed responses and his appeals to religion, he tries (several times) to dismiss Bartleby, assuming after each such decision that Bartleby will heed his word. When Bartleby continues to stand fast, the lawyer instead moves his own offices. When questioned about Bartleby by the lawyer who took up occupancy in his former office, the lawyer, like Peter with respect to Jesus, three times denies any relation to or knowledge of him. Yet he will voluntarily converse with Bartleby two more times, trying again on both occasions to help him by offering, among other things, to take him to his own home and later, after Bartleby is removed to the Tombs, by making sure that he is well fed.

- How does the lawyer see Bartleby? Does he see him as anything more than “Bartleby, the Scrivener”?

- What do you think of the lawyer’s treatment of Bartleby? Is it commendable? Deplorable? Understandable? Or something else? Is there anything else the lawyer should have done? How would you act if you were in the lawyer’s place?

- Does he, on balance, “do well by” Bartleby—or not?

- What is the source of Bartleby’s “wondrous ascendancy” over the lawyer (25)? Or, why does the lawyer put up with him? Should he have?

- Do you think the lawyer learns anything from Bartleby? If not, why not? If yes, when and what does he learn? (In this regard, think particularly about what he might mean when he says, “For a few moments I was turned into a pillar of salt” [cf. Genesis 19:26], as well as his many other religious references, including his pronouncement, when he finds Bartleby dead: He lies “with kings and counsellors” [cf. Job 3:11-15]). If you don’t think the lawyer learns anything from Bartleby, should he have learned something? If so, what? What have you learned?

WATCH: Does the lawyer, on balance, “do well by” Bartleby—or not?

D. Coda

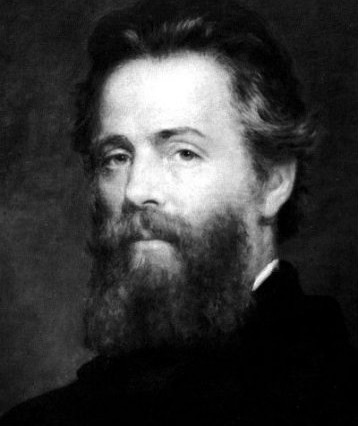

Early in 1853, Melville was asked by Putnam’s Magazine, the nation’s then-leading literary monthly, to contribute a work of short fiction. Apparently, he began by writing a story about a young wife who waits seventeen years for news from her husband, who left home to find work. As Melville conceived the story, the mailbox was a reminder of the passage of time: unused, it rots and falls apart. Word never comes. For unknown reasons, this story was abandoned, but the forlorn mailbox and the absent mail seem to have found themselves into the Dead Letter Office, which is mentioned in the coda to “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” the story that was in fact published at the end of the same year. In the coda, the mention of the Dead Letter Office is intended to give us some idea about the life of Bartleby prior to the events narrated in the story. But the lawyer/narrator specifically warns us that the information he divulges is an “item of rumor”: “hence, how true it is I cannot now tell.” He includes it, he tells us, because of its “suggestive interest” to him and possibly to us, his readers, as well.

- Does the coda help you to better understand Bartleby? If so, in what way(s)?

- What would it have been like to work in the Dead Letter Office? What effect do you think it had on Bartleby, and why? How do you think his work in the Dead Letter Office may have changed the way he viewed his work as a scrivener?

- Does the coda help you to better understand the lawyer? If so, does it change your assessment of the lawyer? For better or for worse? What is the lawyer’s own relationship with letters? With human communication in general?

- What is the meaning of the lawyer’s final exclamation, “Ah Bartleby! Ah humanity!” (37)

WATCH: What is the work of a scrivener? What is Bartleby and the lawyer's relationship with letters?

The video seminar helps capture the experience of high-level discourse as particpants interact and elicit meaning from classic American texts. To watch the full conversation, click here. Otherwise click below to continue.

(3 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(3 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

Post a Comment