Introduction

In declaring that “I, Too, Sing America,” Langston Hughes raises the question of how we as Americans should relate to one another. (In the poem, Hughes likens America to a kind of family, where he is the “darker brother,” at the moment outcast but eventually included: “Besides, They’ll see how beautiful I am / And be ashamed.”) In this selection, Robert Frost also raises questions about neighborliness and inclusion, but in quite a different way than Hughes.

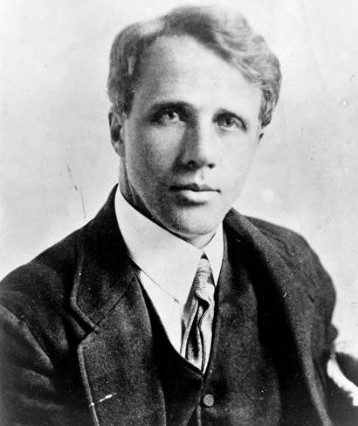

Frost (1874–1963) was born in San Francisco in 1874 and moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts as a child. He attended Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, but left without graduating to help support his family by working odd jobs. Frost returned to poetry in 1894 when he sold his first poem, “My Butterfly.” He married a year later and moved to a farm in Derry, New Hampshire. Inspired by his surroundings, Frost began using the imagery and themes of life in rural New England to explore philosophical questions in his poems. Frost and his family relocated to England in 1912 where he published his first two books. Frost returned to New Hampshire at the outbreak of World War I and embarked on a nearly 40-year collegiate teaching career. In 1924, Frost won his first Pulitzer Prize for his volume of poems, New Hampshire, and he would go on to win the award three more times over the next two decades. Frost served as the Poet Laureate for the United States from 1958 to 1959.

First published in 1915 as part of Frost’s second collection of poetry, North of Boston, the poem, written in blank verse, describes how two neighbors come together each spring to fix a stone wall that divides their property. The speaker in the poem wonders if the wall is actually necessary—“He is all pine and I am apple orchard. / My apple trees will never get across / And eat the cones under his pines”—but his neighbor only responds “Good fences make good neighbors.” And so Frost paints a portrait of the two men, one who questions the yearly repair of the wall (but who continues to participate in the activity), and the other who is driven by tradition to build up the wall.

As you read “Mending Wall,” consider these questions: Why do the two men repair the wall each year? Do they have different reasons for doing so? What are ways that fences do make good neighbors? What are ways they do not? What responsibilities do we have toward our neighbors? And what does Frost’s poem tell us about neighborliness? Do good fences make good neighbors?

Post a Comment