Introduction

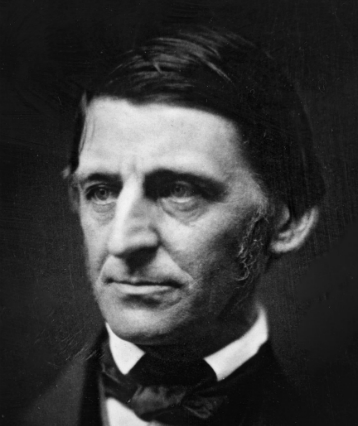

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82), essayist, poet, and leader of the Transcendentalist movement, was a staunch abolitionist and a vigorous supporter of the Union during the Civil War. In 1861, at the beginning of the conflict, many young men, both Northerners and Southerners, quickly enlisted, most of whom were eager for adventure or in search of honor and glory. But as the war continued and the casualties mounted, many of the initial recruits became war-weary, and recruiting new soldiers became much more difficult. Seeking to inspire more volunteers to join the Union cause, Emerson wrote this poem, published in the Atlantic in 1863. The famous last quatrain of Part III has been inscribed on veterans’ memorials throughout the United States.

Emerson begins with slavery. How does he present the plight of the slaves? How does he account for its presence in the United States? What do the last four lines, with Destiny personified, imply about the meaning of the current war? Freedom, also personified, is the subject of Part II. What is the poet’s account of freedom’s progress? What is the meaning of the last four lines of this part?

Part III deals with the critical issue, how to inspire youths who love frolic and ease to go to war in the cause of freedom. What is the meaning of the poem’s answer, given in the closing quatrain of this part? Who or what summons them, and why do they respond? Is Emerson describing the way things are, or is he inviting his listeners to hearken to the way things should be? What picture does he paint, in Part IV, of the different fates of those who serve Justice (or God) and those who do not? How might such an account affect the conduct of his preferred audience? The poem finishes by viewing the victory of “Eternal Rights.” What does Emerson mean by saying “these are gods, / All are ghosts beside”? What is the meaning of the poem’s title?

How are you moved by the poem? Were you a young reader in 1863, would it have moved you to enlist? Which words or images would you have found most compelling?

I.

Low and mournful be the strain,

Haughty thought be far from me;

Tones of penitence and pain,

Moanings of the Tropic sea;

Low and tender in the cell

Where a captive sits in chains,

Crooning ditties treasured well

From his Afric’s torrid plains.

Sole estate his sire bequeathed—

Hapless sire to hapless son—

Was the wailing song he breathed,

And his chain when life was done.

What his fault, or what his crime?

Or what ill planet crossed his prime?

Heart too soft and will too weak

To front the fate that fetches near,—

Dove beneath the vulture’s beak;—

Will song dissuade the thirsty spear?

Dragged from his mother’s arms and breast,

Displaced, disfurnished here,

His wistful toil to do his best

Chilled by a ribald jeer.

Great men in the Senate sate,

Sage and hero, side by side,

Building for their sons the State

Which they shall rule with pride.

They forebore to break the chain

Which bound the dusky tribe,

Checked by the owners’ fierce disdain,

Lured by “Union” as the bribe.

Destiny sat by, and said,

“Pang for pang your seed shall pay,

Hide in false peace your coward head,

I bring round the harvest-day.”

II.

Freedom all winged expands,

Nor perches in a narrow place,

Her broad van1 seeks unplanted lands,

She loves a poor and virtuous race.

Clinging to the colder zone

Whose dark sky sheds the snow-flake down,

The snow-flake is her banner’s star,

Her stripes the boreal streamers are.

Long she loved the Northman well;

Now the iron age is done,

She will not refuse to dwell

With the offspring of the Sun

Foundling of the desert far,

Where palms plume and siroccos2 blaze,

He roves unhurt the burning ways

In climates of the summer star.

He has avenues to God

Hid from men of northern brain,

Far beholding, without cloud,

What these with slowest steps attain.

If once the generous chief arrive

To lead him willing to be led,

For freedom he will strike and strive,

And drain his heart till he be dead.

III.

In an age of fops and toys,

Wanting wisdom, void of right,

Who shall nerve heroic boys

To hazard all in Freedom’s fight,—

Break sharply off their jolly games,

Forsake their comrades gay,

And quit proud homes and youthful dames,

For famine, toil, and fray?

Yet on the nimble air benign

Speed nimbler messages,

That waft the breath of grace divine

To hearts in sloth and ease.

So nigh is grandeur to our dust,

So near is God to man,

When duty whispers low, Thou must,

The youth replies, I can.

IV.

Oh, well for the fortunate soul

Which Music’s wings infold,

Stealing away the memory

Of sorrows new and old!

Yet happier he whose inward sight,

Stayed on his subtile3 thought,

Shuts his sense on toys of time,

To vacant bosoms brought.

But best befriended of the God

He who, in evil times,

Warned by an inward voice,

Heeds not the darkness and the dread,

Biding by his rule and choice,

Feeling only the fiery thread

Leading over heroic ground,

Walled with mortal terror round,

To the aim which him allures,

And the sweet heaven his deed secures.

Stainless soldier on the walls,

Knowing this,—and knows no more,—

Whoever fights, whoever falls,

Justice conquers evermore,

Justice after as before,—

And he who battles on her side,

—God— though he were ten times slain—

Crowns him victor glorified,

Victor over death and pain;

Forever: but his erring foe,

Self-assured that he prevails,

Looks from his victim lying low,

And sees aloft the red right arm

Redress the eternal scales.

He, the poor foe, whom angels foil,

Blind with pride, and fooled by hate,

Writhes within the dragon coil,

Reserved to a speechless fate.

V.

Blooms the laurel which belongs

To the valiant chief who fights;

I see the wreath, I hear the songs

Lauding the Eternal Rights,

Victors over daily wrongs:

Awful victors, they misguide

Whom they will destroy,

And their coming triumph hide

In our downfall, or our joy:

Speak it firmly,—these are gods,

All are ghosts beside.

2

A warm wind, usually blowing from the Libyan deserts to the coast of Italy. Return to text.

Return to The Meaning of Memorial Day.

Post a Comment