Death in the Civil War

Memorial Day grew out of the grief and tragedy wrought by the Civil War, and to appreciate the day—and continue its traditions—one must first understand the context from which it arose.

On April 9, 1865, at the McLean House in Appomattox Court House, Virginia, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to General Ulysses S. Grant, commander of the armies of the United States. Though it took another few months for the remaining Confederate armies to follow Lee’s example and for hostilities to end, Lee’s surrender signaled the close to the bloodiest four years in US history.

By the end of the Civil War, some 750,000 Americans in the North and South—more than two percent of the population—had been killed. In 2013 numbers, such a percentage would exact a death toll of more than 6.3 million Americans. As historian Drew Gilpin Faust notes in her vivid portrayal of death and the Civil War, This Republic of Suffering, during the war “loss became commonplace; death’s threat, its proximity, and its actuality became the most widely shared of the war’s experiences.” She continues:

[F]or those Americans who lived in and through the Civil War, the texture of the experience, its warp and woof, was the presence of death. . . . As they faced horrors that forced them to question their ability to cope, their commitment to the war, even their faith in a righteous God, soldiers and civilians alike struggled to retain their most cherished beliefs, to make them work in the dramatically altered world that war had introduced. Americans had to identify—find, invent, create—the means and mechanisms to manage more than half a million dead: their deaths, their bodies, their loss. How they accomplished this task reshaped their individual lives—and deaths—at the same time that it redefined their nation and their culture. The work of death was Civil War America’s most fundamental and most demanding undertaking.

Dying away from home was an especially distressing prospect for Civil War Americans. The last words of the dying were given an especial significance by these Victorian Christians, for they represented the state of the soon-to-be-departed’s eternal soul. Parents and siblings who were given news of their loved one’s injuries rushed to the battlefield hospital to care for their dying beloved and to witness his final moments. More often, news came too late—if it came at all—and so others tried to record the last breaths of their dying comrades—or, in some cases, of their enemy. Hospital workers and other civilians likewise tried to bridge the divide between battlefield and home, writing letters to next-of-kin, encouraging soldiers to write their families, and filling in for absent mothers and sisters. Many did so with the hope that their own soldiers might be receiving the same care elsewhere should they need it. One popular wartime song described the gratitude those at home had for such nurses and caregivers:

Bless the lips that kissed our darling,

As he lay on his death-bed,

Far from home and ’mid cold strangers

Blessings rest upon your head. . . .

O my darling! O our dead one!

Though you died far, far away,

You had two kind lips to kiss you,

As upon your bier you lay.

Being buried away from home was a constant worry for the soldiers themselves. Letters from the period are filled with soldiers’ wishes to be buried in their family plots, and some dying soldiers used their last written words to describe where they had fallen so their families could come and retrieve their bodies. “Death is near,” wrote 26-year-old James Montgomery in a blood-stained letter to his father in Mississippi, “I will die far from home. . . . I would like to rest in the graveyard with my dear mother and brothers.” His sentiment was a common one.

When a family came looking for their deceased, their search—even if they knew generally where to look—often ended in anguish. (The Montgomery family, despite their efforts, never found James’ grave.) Due to the incredible scale of carnage, the bodies of most dead soldiers were, of necessity, treated impersonally. Though an officer could expect that his body would be sent home to his family, the remains of the enlisted were treated with less care. Burial was haphazard, frequently en masse—especially if the graves were for the enemy dead—and it was not uncommon for shallowly-dug burial grounds to give up their dead when a change of the weather demanded them.

A Civil War Holiday

Given the broad reach of death, soon after the Civil War ended grassroots efforts to honor the dead arose. Citizens first sought to identify and properly bury the fallen soldiers. Clara Barton, a Civil War nurse and founder of the American Red Cross, established the Missing Soldiers Office to help families find information about their missing loved ones. Edmund Burke Whitman, a quartermaster during the war, became the superintendent of America’s new national cemeteries—established by Congress in 1867—and led expeditions to the war-torn South to find the buried Union dead; with the aid of black troops and former slaves, he located more than 100,000 graves. By 1870, the nation had re-interred some 300,000 Union soldiers in the new federal cemeteries. Roughly 120,000 of them remained unidentified.

In April 1865—the month that Abraham Lincoln was assassinated—blacks in Charleston, South Carolina performed their own re-burial service. Four long years after the war had begun there, the city lay in ruins. Most of the city’s white population had deserted the city and so were not around to see the 21st US Colored Infantry Regiment march into Charleston that spring. The regiment was instead greeted by the thousands of former slaves who still lived there.

During the final years of the war, Confederates had converted the city’s Washington Race Course and Jockey Club into an outdoor prison, and at least 250 Union soldiers succumbed to exposure and disease there. Now, a small group of black workmen re-buried the Union dead who had been buried in a mass grave behind the track’s grandstand and built a whitewashed fence around the new cemetery, naming it “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

On May 1, 10,000 Charlestonians—many of them former slaves—paraded around the slaveholders’ race course, with the procession led by 3,000 black children carrying flowers and singing “John Brown’s Body.” Historian David W. Blight describes what came next:

The children were followed by three hundred black women representing the Patriotic Association, a group organized to distribute clothing and other goods among the freed people. The women carried baskets of flowers, wreaths, and crosses to the burial ground. The Mutual Aid Society, a benevolent association of black men, next marched in cadence around the track and into the cemetery, followed by large crowds of white and black citizens. . . . [T]hey declared the meaning of the war in the most public way possible—by their labor, their words, their songs, and their solemn parade of roses, lilacs, and marching feet on the old Planters’ Race Course. One can only guess at which passages of scripture were read at the graveside on this first Memorial Day. But among the burial rites the spirit of Leviticus was surely there: “For it is the jubilee; it shall be holy unto you . . . in the year of this jubilee ye shall return every man unto his possession.”

After the dedication of the cemetery, the crowds retired to hear speeches, enjoy picnics, and watch parading Union soldiers—much like a modern-day Memorial Day.

Other cities—approximately 25—also claim to be the progenitor of Memorial Day, originally called Decoration Day.1 In March 1866, for example, nearly a year after the parade in Charleston, the Ladies Memorial Association of Columbus, Georgia set aside April 26 as a day to “wreath the graves of our martyred dead with flowers”—and encouraged women elsewhere to do the same. In many Southern states, April 26 is still celebrated as Confederate Memorial Day. In 1966, Congress and President Lyndon B. Johnson tried to settle the question by declaring Waterloo, New York as the birthplace of Memorial Day, for it was there that, on May 5, 1866, businesses closed and residents flew flags at half-staff in commemoration of the Civil War dead.1

But Decoration Day did not take on a widespread prominence and become a shared day of celebration until May 1868. John A. Logan, a retired general in the US Army and commander in chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization of Union Civil War veterans, set aside May 30 of that year “for the purpose of strewing with flowers, or otherwise decorating, the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, hamlet, and churchyard in the land.”

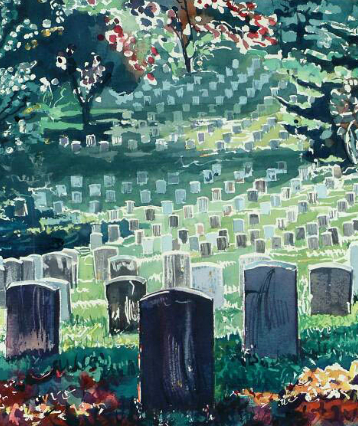

Logan’s orders were heeded, and three years after the Civil War ended a crowd of 5,000 gathered at Arlington National Cemetery. At the ceremony, Congressman and future president James A. Garfield spoke, and veterans and orphaned children decorated the graves of their fallen comrades, countrymen, and family members. Similar ceremonies were held that day at 183 cemeteries across 27 states. The following year, 336 cities in 31 states—including in the South—observed the call to remembrance.

Memorial Day: Beyond the Civil War

In 1873, New York became the first state to institutionalize the observance of Decoration Day on May 30. By 1890, all the Northern states had done so. As the meaning of the day shifted from celebrating the cause of the Union to a more general commemoration of the Civil War and its dead, Southern states also made Decoration Day their own. Over time, too, the name of the holiday shifted from Decoration Day to Memorial Day, perhaps to encompass the feeling that memorializing entails an act even greater than simply decorating or caring for the resting place of the fallen. “Memorial Day,” Blight writes, “provided a means to achieve both spiritual recovery and historical understanding. . . . [It] became a legitimizing ritual of the new American nationalism forged out of the war.”

With over 116,000 Americans killed in World War I, Memorial Day broadened its scope even further in order to honor all of America’s war dead. As in other allied countries, Americans began using the poppy as a flower of remembrance, and the sale of poppies was used to provide aid to children orphaned by the war. (The popularity of the poppy comes from John McCrae’s 1915 poem “In Flanders Fields,” in which the Canadian soldier paints a haunting picture of the flowers growing amid the graves of World War I.)

After World War II—in which another 405,000 American lives were lost—Memorial Day also became a day to pray for peace, and since 1950 every president has included such a plea in his Memorial Day remarks. Since the year 2000, each president has also asked Americans to pause at 3 p.m. local time for a moment of silent reflection.

One hundred years after John Logan issued his order for the first national Decoration Day, in 1968, Congress finally declared Memorial Day a national holiday.2 In so doing, however, Congress moved the celebration from May 30 to the last Monday in May, as part of the Uniform Holiday Bill that created the three-day weekend, in part, “to stimulate greater industrial and commercial production.” As with the other holidays affected—Washington’s Birthday, Labor Day, Columbus Day, and Veterans Day—the change has been met with some resistance, and many veterans’ groups advocated for returning the day’s observance to May 30.

Despite the distractions, despite the long weekends and barbecues and beginning-of-summer festivities, many Americans still memorialize the nation’s dead each May. About 5,000 people gather each year at Arlington National Cemetery, where the president or the vice president of the United States places a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. (“Here rests in honored glory an American soldier known but to God.”) Members of the Army’s Third US Infantry (“The Old Guard”) place miniature American flags in front of more than 260,000 gravestones at the national cemetery. Communities across the nation hold similar ceremonies, decorating graves, attending parades, giving speeches, remembering the dead, and enjoying food and one another—just as the first American celebrators of Memorial Day did 150 years ago.

2 90th US Congress Title 5, U.S.C. § 6103 a, June 28, 1968.

Return to text.

Return to The Meaning of Memorial Day.

(3 votes, average: 4.67 out of 5)

(3 votes, average: 4.67 out of 5)

Post a Comment