Martin Luther King Jr. Day is the only federal holiday that honors a private American citizen, and, with the celebration of George Washington’s Birthday and Columbus Day, one of just three holidays honoring a specific person. Calls for a holiday to honor King began immediately following his death. A 15-year effort on the part of lawmakers and civil rights leaders, buoyed by popular support, culminated in 1983 when the US Congress passed legislation that officially designated the third Monday in January as a federal holiday. However, controversy continued to surround the day, and it was not until 2000 that every state celebrated a holiday in honor of King. Today, Americans use this anniversary not only to pay tribute to one man’s efforts in the cause of equal rights, but also to celebrate the Civil Rights Movement as a whole.

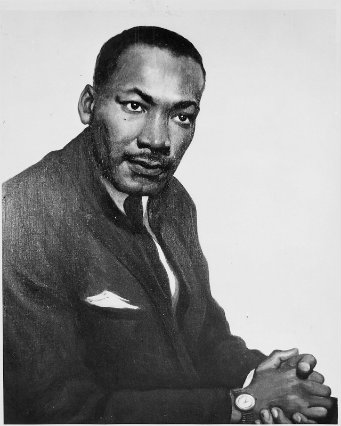

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. was born in Atlanta, Georgia on January 15, 1929, the second of three children to Reverend Martin Luther King Sr. and his wife Alberta. Growing up, King Jr. attended Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, where his grandfather and father served as pastors. He graduated from a segregated high school at 15 and entered Morehouse College in 1945. Though initially uncertain about whether he wanted to enter the ministry, King chose to follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather and was ordained during his senior year of college. He then continued his studies at the Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania, where he was elected class president of the majority-white student body and graduated with distinction in 1951. While a doctoral student in systematic theology at Boston University, King met Coretta Scott, a music student originally from Alabama. The coupled married in 1953 and had four children over the next decade: Yolanda, Martin Luther III, Dexter, and Bernice.

As a graduate student, King developed and refined the personal beliefs that would guide his leadership of the Civil Rights Movement. The doctrine of the Social Gospel, a liberal movement within American Protestantism that applied Christian ethics to social problems, became a guiding force in the young minister’s theology. King’s familial church, Ebenezer Baptist, emphasized social activism, public service, and charity, and his doctoral studies reinforced these teachings. In a 1952 letter to Coretta, King reaffirmed his belief in the Social Gospel, writing that he would “hope, work, and pray that in the future we will live to see a warless world, a better distribution of wealth, and a brotherhood that transcends race or color. This is the gospel that I will preach to the world.”

It was also while studying theology that King first encountered the philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi, whose advocacy of nonviolence deeply resonated with him. The Indian independence leader’s success in using nonviolent civil disobedience led King to hope that the same tactics could work for African Americans in the United States. King believed that nonviolent civil disobedience “breaks with any philosophy or system which argues that the ends justify the means. It recognizes that the end is pre-existent in the means.” Moreover, King argued that nonviolence prevents “discontent from degenerating into moral bitterness and hatred,” which “is as harmful to the hater as it is to the hated.” While the Social Gospel provided the moral imperative for participation in the Civil Rights Movement, Gandhi’s example provided the practical model for King to combat racism and disenfranchisement.

Civil Rights Leader

In 1954, King moved to Montgomery, Alabama to become the minister of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, and his commitment to nonviolence faced its first test the following year during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. A protest against the city’s segregated public buses began when a young African American activist named Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give her seat to a white passenger. Parks’ act of civil disobedience launched the 381-day boycott of public transport, which ended when the US Supreme Court declared the city’s segregationist laws unconstitutional. During the strike, King was attacked, jailed, and threatened, but remained committed to the principles of nonviolence. The Montgomery Bus Boycott proved a major victory for King’s strategy of nonviolent resistance and brought the young minister into the national spotlight.

Three years later, King helped to found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to coordinate nonviolent civil rights activism. In 1963, King led major demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama to combat segregation and unfair hiring practices. Jailed during the protests, King responded to a group of Alabama clergymen opposed to the public demonstrations in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” by emphasizing the values of cooperation and empathy. He argued that all Americans benefit from creating a more equal society, writing, “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” That same year, King led the March on Washington, where he delivered his celebrated “I Have a Dream” speech. A year later, King became the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Though King continued to fight racial inequality and injustice, his vocal opposition to the Vietnam War in the late 1960s left him estranged from former supporters. On April 4, 1968, King traveled to Memphis to support a strike of local sanitation workers. While standing on the balcony of his hotel, King, then age 39, was shot and killed.

A National Holiday

The effort to commemorate Martin Luther King Jr. with a national holiday began immediately after his death. Congressman John Conyers (D-MI) introduced a bill in the House of Representatives to create a national holiday in honor of King’s birthday just four days after his assassination. The Reverend Ralph Abernathy, King’s successor as head of the SCLC, argued that such a holiday would not only pay tribute to King himself, but would also honor the achievements of black Americans more broadly: “At no other time during the year does this Nation pause to pay respect to the life and work of a black man.”1 Others argued that such a holiday would signal the support of Americans of all races both for King’s work in particular and for the Civil Rights Movement in general.

Though Conyers’ bill was unsuccessful, King’s birthday became an important holiday in communities across the country. Many public schools and local governments nationwide closed on the day, and civic groups and institutions celebrated the day with vigils, marches, and speeches. In 1973, Illinois became the first state to create a holiday in observance of King’s birthday, and a number of states soon passed similar legislation. Coretta Scott King founded the King Center in Atlanta in 1968 to continue the work of her late husband, and the organization became a prominent advocate for establishing a national holiday during the 1970s.

Conyers reintroduced legislation in Congress in 1979 for a federal King holiday, and though it garnered more support, the bill still fell five votes short of passing. Opponents raised several arguments against the proposal. Many cited fiscal concerns, arguing that adding another paid government holiday to the calendar was an unnecessary public expense. Others questioned whether King, who never held a public office or served in the military, warranted a public holiday alongside George Washington, the only other American celebrated with a holiday, at the exclusion of other leaders such as Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson. Finally, some congressional objections to the proposal centered on King’s criticism of the Vietnam War and his alleged ties to communism.

Despite these reservations, the proposed holiday continued to gain popular support, and the SCLC coordinated a widespread campaign to win congressional votes. In 1981, singer Stevie Wonder released the single, “Happy Birthday,” to draw attention to the cause, and a petition with over six million signatures in support of a King holiday arrived in Washington. Finally, after a hard-fought battle in the Senate, Congress in 1983 passed a bill establishing the third Monday in January as a federal holiday, with its celebration to begin in 1986.2 After signing the bill into law, President Ronald Reagan remarked, “Each year on Martin Luther King Day, let us not only recall Dr. King, but rededicate ourselves to the Commandments he believed in and sought to live every day: Thou shall love thy God with all thy heart, and thou shall love thy neighbor as thyself.” At the same ceremony, Coretta Scott King declared, “This is not a black holiday; it is a people’s holiday.”

Even after it was recognized by the federal government, the holiday remained contested. The decision over whether or not to celebrate the holiday still fell to each state, and the 23 states that had not already established holidays in honor of King before 1986 could decide whether or not to mark the day. In the year 2000, South Carolina became the last state to recognize Martin Luther King Jr. Day, 17 years after it became a federal holiday. Today, many Americans view the holiday as a time to honor the legacy of King through community service, in keeping with the emphasis introduced by the King Holiday and Service Act that Congress passed in 1994. The King Center notes that, “Martin Luther King Jr. Day is not only for celebration and remembrance, education and tribute, but above all a day of service.”

In 2011, a monument to King was unveiled on the National Mall in Washington, DC, another tribute to the important legacy of the civil rights leader. President Barack Obama emphasized King’s legacy of cooperation and service for the greater good: “We need more than ever to take heed of Dr. King’s teachings. He calls on us to stand in the other person’s shoes; to see through their eyes; to understand their pain. . . . He also understood that to bring about true and lasting change, there must be the possibility of reconciliation; that any social movement has to channel this tension through the spirit of love and mutuality.”

1 “King Holiday Plea Pressed By Abernathy,”

The Washington Post, January, 13, 1969, A18.

Return to text.

2 According to the passed bill, “the amendment […] shall take effect on the first January 1 that occurs after the two-year period following the date of the enactment of this Act.”

Return to text.

Return to The Meaning of Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

(3 votes, average: 3.67 out of 5)

(3 votes, average: 3.67 out of 5)

Post a Comment