In 1768, before the United States was even a nation, a group of journeymen tailors working in New York went on strike to protest a wage reduction, marking the first time in American history that workers joined together in a common labor movement. Twenty-six years later, the first formal labor union was established in Philadelphia when shoemakers came together to form the Federal Society of Journeymen Cordwainers. In 1805, the union workers went on strike in an effort to secure higher wages, but the union’s leaders were indicted and convicted under criminal conspiracy charges and the strike collapsed.

Despite the failure of the union’s strike, other craft labor unions soon began to form in cities across America. These unions, mainly composed of skilled workers, set prices for their members’ work, defended their trade against cheaper, unskilled labor, and advocated for a shorter, ten-hour workday. These early unions pursued a relatively narrow strategy, focused on the immediate material interests of their members while largely ignoring broader social issues—or even labor issues affecting other unions and nonorganized unskilled workers. Their efforts typically took the form of small, local strikes in which key workers refused to work until the union’s demands were met.

Beginning with the New York Workingmen’s Party (founded in 1829), however, unions began to take on broader goals and work with one another to achieve them. In 1833, for example, carpenters in New York went on strike for higher wages and were supported throughout their strike by donations from other tradesmen. This cooperative strike led to the formation of the General Trades’ Union of New York in the same year, formally bringing together delegates from nine different craft unions.

A central aim of these union organizations was the adoption of the eight-hour workday—a demand first voiced in Great Britain by Robert Owen in 1817 (the year before, he had pioneered a shorter workday by instituting a ten-hour day in his factories at New Lanark, Scotland). In America, Boston carpenters first achieved the eight-hour day in 1842, and Illinois passed a law in 1867 that, although largely ineffective, guaranteed workers in the state an eight-hour day. The following year, the US Congress granted federal workers the limited workday as well.

The Rise of National Labor Organizations

As the Civil War drew to a close, national labor organizations such as the National Labor Union (est. 1866) and the Knights of Labor (est. 1869) began to form, turning their attention to nationwide labor reform. The Knights of Labor, for instance, welcomed nearly all workers (with the exception of members of the professional classes, such as lawyers, bankers, and stockbrokers), and in the mid-1880s, as membership rose to nearly a million, led national strikes against the Union Pacific and Missouri Pacific railroad companies. In 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions—the precursor to the American Federation of Labor (AFL)—passed a resolution declaring that “eight hours shall constitute a legal day’s labour from and after May 1, 1886” and called on labor organizations across the country to host parades and strikes on that day.

Though hundreds of thousands of workers participated in these events, success was limited. The Knights’ national railroad strike failed because the railroads were able to hire other unskilled workers to replace those on strike, and many of the skilled workers—such as the Brotherhood of Engineers—refused to strike altogether. The May Day strike of 1886 collapsed in the wake of the disastrous Haymarket Affair in Chicago. There, striking workers rallied outside the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company factory at the end of the workday on May 3, as strikebreakers (workers not participating in the strike) left the building. When strikers confronted these new workers, police gunfire erupted and killed at least two McCormick workers. In retaliation, local anarchists called a rally for the following day at the Haymarket Square. After a day of speeches by labor leaders, at about 10:30 p.m., the police sought to disperse the crowd, and an anonymous protester threw a homemade dynamite bomb in the path of the advancing police, killing seven policemen and wounding at least 60 men.

In response to the increasingly radical and violent character of the labor movement, union leaders met in December 1886 in Columbus, Ohio, to create an alliance organization with more moderate leadership than the Knights of Labor. Under the presidency of Samuel Gompers, head of the Cigarmakers’ International Union, the American Federation of Labor rejected the radical politics of other labor activists and sought to work within the American economic system to seek reform. Because the AFL was mainly composed of craft unions, their collective bargaining efforts were much more successful than those attempted by the unskilled workers in the Knights of Labor.

Frustration with the slow pace of reform led some union leaders to adopt more aggressive methods. In May 1894, roughly 4,000 workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company began to strike to protest reductions to their wages. The American Railway Union, led by Eugene V. Debs, a future five-time Socialist Party of America candidate for president, supported the strikers by calling for railroad workers across the country to boycott any work involving Pullman train cars. By the end of June, 125,000 railroad workers had quit their jobs in protest, and railways across the nation were severely hindered by the strike. As railroad companies began hiring replacement workers, protesters became increasingly desperate, physically assaulting the strikebreakers and, in some cases, even derailing locomotives from their tracks and setting buildings on fire. The railroad companies turned to the federal government for help. President Grover Cleveland sent in 12,000 troops to break the strike—an action the AFL supported—and Debs himself was sent to prison and the American Railway Union was dissolved.

Labor Conditions Exposed

In the early 1900s, muckraker journalists and government officials began to expose the terrible working conditions faced by many day-laborers in American factories. Between 1902 and 1907, The Factory Inspector—the unofficial journal of the International Association of Factory Inspectors—recorded numerous cases of workers who were burned alive by molten steel or of machinists who lost arms and legs in factory equipment. In a 1907 investigation of the steel industry, writer William B. Hard estimated that roughly 1,200 men—about 10 percent of the steel industry’s workforce—were killed or injured each year on the job. Of these, fewer than 250 of the men or their families were compensated for the loss of life or limb.

Working conditions were often poor for women and children as well. According to a 1906 study by the Association of Neighborhood Workers, more than 130,000 women were working in roughly 39,000 factories in New York City. Although a city law capped the workweek for women at sixty hours (allotted over six days), nonenforcement of the statute was the norm, and employers remained confident that any government attempt to limit their employees’ working hours would be held unconstitutional. Women and children frequently reported that if they refused to work overtime when their employer requested, they would be fired. At times, when garment producers received time-sensitive orders for new dresses and other clothing, the seamstresses would be held in the factories until the early morning hours to complete their part of the sewing.

In addition to working in garment mills, children were regularly employed in industrial factories, coal mines, newspapers, and, of course, on farms. By the year 1900, nearly 20 percent of American workers were under the age of 16, and in many southern cotton mills, a quarter of the workers were below the age of 15—and half of these were younger than 12. In 1904, the New York Times estimated that nearly three million children ages 10 to 15 worked for wages every day. The National Child Labor Committee, formed in 1904, sought to raise awareness about the plight of working children. One of their first actions was to hire sociologist Lewis Wickes Hine to photograph child laborers. Hine’s heart-wrenching portraits of young children working in coal mines, meatpacking houses, textile mills, and other industries did much to advance the cause of child labor reform and led to the establishment of a Children’s Bureau in both the US Department of Commerce and the US Department of Labor.

Tragedy and Reform

In 1909 and 1910, the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union organized strikes by New York City’s garment workers and cloakmakers to protest the sweatshop conditions, long hours, and low pay. These strikes, involving roughly 80,000 workers—mostly immigrant women—were largely successful, and working conditions were set to improve in much of the industry. Although the strikes of 1909 and 1910 were a watershed moment for the labor movement, the new protections were difficult to enforce and many workers continued to labor in dehumanizing and dangerous conditions.

On Saturday, March 25, 1911, the story of the American laborer arguably took its most tragic turn when someone dropped a match or a burning cigarette onto a heap of fabric on the floor of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City. Within minutes, the entire building was engulfed in flames. Because many of the doors on the building’s eighth and ninth floors were locked, 146 women were either consumed in the fire or jumped from the building to their deaths. Although the owners of the Triangle Waist Company were put on trial and eventually acquitted of wrongdoing (the prosecution was unable to prove they knew the doors were locked), the horrifying memory of the fire and its victims convinced Americans as never before of the need for more vigorous labor reforms.

In 1914, Congress passed the Clayton Antitrust Act, which for the first time specifically provided safe harbor under the law for union activities, including boycotts, peaceful strikes, picketing, and collective bargaining. Also in 1914, the Ford Motor Company shifted its workers to the eight-hour workday—a decision many of its competitors soon followed. Two years later, in the first federal act legislating hours worked by employees of private companies, Congress passed the Adamson Act, establishing an eight-hour day for all railroad workers. After years of lobbying by the National Child Labor Committee and the National Consumers League, in 1916, Congress passed the Keating-Owen Act, which sought to curtail child labor by prohibiting the interstate commerce of goods made in factories in which children were employed. This act, however, was struck down two years later by the Supreme Court, and it would be another 20 years before the federal government succeeded in limiting child labor.

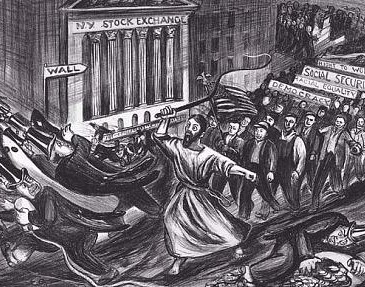

Following a decline in labor union participation in the 1920s, the Great Depression of the 1930s forced businesses to lay off many workers and curtail the benefits that labor had won for employees. As the Depression dragged on, workers continued to lose confidence in the promises of private employers, and they once again turned to the government for assistance. In the 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt pushed through Congress his New Deal package to provide aid to workers—including the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which for the first time established a national minimum wage, severely curtailed and regulated many forms of child labor, and guaranteed “time and a half” pay for any time worked beyond the newly-established eight-hour day. It was this act that fulfilled many of the foundational aims that America’s organized labor movements had been working toward since the beginning of the nation’s history.

World War II and Beyond

World War II fueled another upswing in labor activity, with union membership nearly doubling between 1940 and 1945 as Americans—including women—went to the factories to produce war goods. Labor unions continued to grow in the 1950s, creating a quarter-century-long “golden age” in which workers’ wages grew steadily and union workers earned an average of 20 percent more than their nonunion counterparts. Labor leaders like John L. Lewis (United Mine Workers of America), James “Jimmy” Hoffa (International Brotherhood of Teamsters), George Meany and Lane Kirkland (American Federation of Labor—Congress of Industrial Organizations), and Walter Reuther (United Automobile Workers) became household names, leading a labor movement that by 1953 included nearly a third of America’s private-sector workers. The movement won another victory in 1962 when President John F. Kennedy signed Executive Order 10988, allowing, for the first time, the creation of public-sector unions in the federal government.

The postwar labor movement was not without its fights, however. In 1947, following an active year of postwar strikes involving more than five million American workers, Congress overrode President Harry S. Truman’s veto and passed the Taft-Hartley Act, limiting as “unfair labor practices” certain types of strikes, picketing, and boycotts by unions. Five years later, in the midst of the Korean War, when the United Steelworkers of America led a strike, President Truman nationalized the steel industry in order to prevent a stoppage. The case soon reached the Supreme Court, which ruled that the president did not have the authority to seize the steel mills.

On August 3, 1981, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization declared a strike, demanding better pay and a thirty-two-hour workweek. That afternoon, President Ronald Reagan warned the strikers that they were “in violation of the law and [that] if they do not report for work within 48 hours they have forfeited their jobs and will be terminated.” Two days later, with only 10 percent of the striking workers having returned, the president fired 11,345 air traffic controllers, banning them from federal service for life.

Although organized labor is still a political force, recent decades have seen a decline in the frequency and duration of major strikes and other public actions, as well as a decline in the percentage of Americans who belong to labor unions. (In 2011, only 12 percent of American workers did—and only 7 percent of private-sector workers.)

Return to The Meaning of Labor Day.

Post a Comment