Introduction

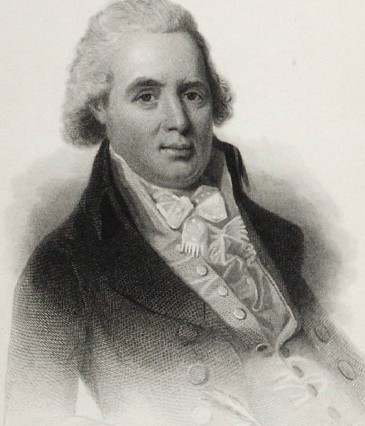

The enthusiastic view of the American Revolution expressed in David Ramsay’s July 4, 1778 oration (see “Oration on the Advantages of Independence”) was not universally shared, especially by the war-weary ordinary soldier. In this letter to his parents, Francis and Mary Shaw, dated June 28, 1779, Samuel Shaw (1754–94), a soldier in the Continental Army, reflects on the state of the army and the difficulties of its soldiers. The “ensuing campaign” he mentions was headed by General Benjamin Lincoln and took place in the southern United States—eventually culminating in the Siege of Charleston and his surrender to the British of his 5,000 men.

Of what does Shaw complain, about the army and for himself? Assuming that Shaw speaks truly, how do you account for the transformation of the initial “patriotic ardor which inspired each breast” into the “avarice and every rascally practice which tends to the gratification of that sordid and most disgraceful passion”? Compare the tone and content of Shaw’s letter with those of Ramsay’s oration at Charleston the previous year. Can both writers be right? Why might seeking the goal of independence by means of war necessarily demoralize and corrupt those who fight?

I wish, seriously, that the ensuing campaign may terminate the war. The people of America seem to have lost sight entirely of the noble principle which animated them at the commencement of it. That patriotic ardor which then inspired each breast,—that glorious, I had almost said godlike, enthusiasm,—has given place to avarice, and every rascally practice which tends to the gratification of that sordid and most disgraceful passion. I don’t know as it would be too bold an assertion to say, that its depreciation is equal to that of the currency,—thirty for one. You may perhaps charitably think that I strain the matter, but I do not. I speak feelingly. By the arts of monopolizers and extortioners, and the little, the very little, attention by authority to counteract them, our currency is reduced to a mere name. Pernicious soever as this is to the community at large, its baneful effect is more immediately experienced by the poor soldier. I am myself an instance of it. For my services I receive a nominal sum,—dollars at eight shillings, in a country where they pass at the utmost for fourpence only. If it did not look too much like self-applause, I might say that I engaged in the cause of my country from the purest motives. However, be this as it may, my continuance in it has brought me to poverty and rags; and, had I fortune of my own, I should glory in persevering, though it should occasion a sacrifice of the last penny. But, when I consider my situation,—my pay inadequate to my support, though within the line of the strictest economy,—no private purse of my own,—and reflect that the best of parents, who, I am persuaded, have the tenderest affection for their son, and wish to support him in character, have not the means of doing it, and may, perhaps, be pressed themselves,—when these considerations occur to my mind, as they frequently do, they make me serious; more so than my natural disposition would lead me to be. The loss of my horse, by any accident whatever (unless he was actually killed in battle, and then I should be entitled only to about one third of his value), would plunge me in inextricable misfortune; two years’ pay and subsistence would not replace him. Yet, the nature of my office renders it indispensable that I should keep a horse. These are some of the emoluments annexed to a military station. I hardly thought there were so many before I began the detail; but I find several more might be added, though I think I have mentioned full enough.

Believe me, my dear and honored parents, that I have not enumerated these matters with a view to render you uneasy. Nothing would give me more pain, should they have that effect; but I think communicating one’s difficulties always lessens, and, of course, makes them more tolerable; and I fancy it has already had some influence on me. I feel much easier than when I began to write, and more reconciled to my lot. It is true I shall see many persons grown rich at the end of the war, who at the commencement of it had no more than myself; but I shall not envy them. I must, notwithstanding, repeat my wish that this campaign may put an end to the war, for I much doubt the virtue of the people at large for carrying it on another year. Had the same spirit which glowed in the breast of every true American at the beginning of the controversy been properly cherished, the country, long ere now, had been in full enjoyment of the object of our warfare,—“peace, liberty, and safety.” But, as matters are at present circumstanced, it is to be feared these blessings are yet at a distance. Much remains to be done for the attainment of them. The recommendations of Congress, in their late address to the inhabitants of the States, should be in good earnest attended to. We are not to stand still and wait for salvation, but we must exert ourselves,—be industrious in the use and application of those means with which Heaven has furnished us, and then we may reasonably hope for success.

Return to The Meaning of Independence Day.

Post a Comment