Introduction

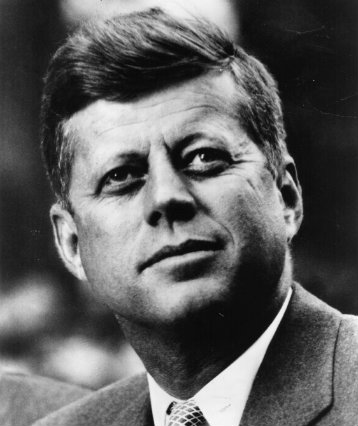

On August 2, 1943, then-Lieutenant (j.g.) John F. Kennedy (1917–63) was commanding a patrol torpedo boat off the Solomon Islands in the Pacific Theater when a Japanese destroyer rammed and sunk his vessel. Despite injuring his back in the collision, Kennedy towed an injured crewman to an island by clinching the man’s lifejacket strap in his teeth as they swam to shore. Kennedy then swam many more hours to secure aid and food after getting the rest of his crew ashore. For his “outstanding courage, endurance and leadership [that] contributed to the saving of several lives,” he was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal. He wrote this letter home shortly after this experience.

What can his parents—and we readers—learn from young Lieutenant Kennedy’s letter about the experience of war? What can we learn about how people at home should speak about it? As president of the United States, Kennedy committed hundreds of thousands of American troops to fight in Vietnam, in a war that lasted over a decade. Can you understand how the author of this letter might have seen fit to do so?

Dear Mother & Dad:

Something has happened to Squadron Air Mail—none has come in for the last two weeks. Some chowder-head sent it to the wrong island. As a matter of fact, the papers you have been sending out have kept me up to date. For an old paper, the New York Daily News is by far the most interesting. . . .

In regard to things here—they have been doing some alterations on my boat and have been living on a repair ship. Never before realized how badly we have been doing on our end although I have always had my suspicions. First time I’ve seen an egg since I left the states.

As I told you, Lennie Thom, who used to ride with me, has now got a boat of his own and the fellow who was going to ride with me has just come down with ulcers. (He’s going to the States and will call you and give you all the news. Al Hamn). We certainly would have made a red-hot combination. Got most of my old crew except for a couple who are being sent home, and am extremely glad of that. On the bright side of an otherwise completely black time was the way that everyone stood up to it. Previous to that I had become somewhat cynical about the American as a fighting man. I had seen too much bellyaching and laying off. But with the chips down—that all faded away. I can now believe—which I never would have before—the stories of Bataan and Wake. For an American it’s got to be awfully easy or awfully tough. When it’s in the middle, then there’s trouble. It was a terrible thing though, losing those two men. One had ridden with me for as long as I had been out here. He had somewhat shocked by a bomb that had landed near the boat about two weeks before. He never really got over it; he always seemed to have the feeling that something was going to happen to him. He never said anything about being put ashore—he didn’t want to go—but the next time we came down the line I was going to let him work on the base force. When a fellow gets the feeling that he’s in for it, the only thing to do is to let him get off the boat because strangely enough, they always seem to be the ones that do get it. I don’t whether it’s just coincidence or what. He had a wife and three kids. The other fellow had just come aboard. He was only a kid himself.

It certainly brought home how real the war is—and when I read the papers from home and how superficial is most of the talking and thinking about it. When I read that we will fight the Japs for years if necessary and will sacrifice hundreds of thousands if we must—I always like to check from where he is talking—it’s seldom out here. People get so used to talking about billions of dollars and millions of soldiers that thousands of dead sounds like drops in the bucket. But if those thousands want to live as much as the ten I saw—they should measure their words with great, great care. Perhaps all of that won’t be necessary—and it can all be done by bombing. We have a new Commodore here—Mike Moran—former Captain of the Boise—and a big harp if there ever was one. He’s fresh out from six months in the States and full of smoke and vinegar and statements like—it’s a privilege to be here and we would be ashamed to be back in the States—and we’ll stay here ten years if necessary. That all went over like a lead balloon. However, the doc told us yesterday that Iron Mike was complaining of headaches and diarrhea—so we look for a different tune to be thrummed on that harp of his before many months.

Love,

Jack

Return to The Meaning of Veterans Day.

Post a Comment