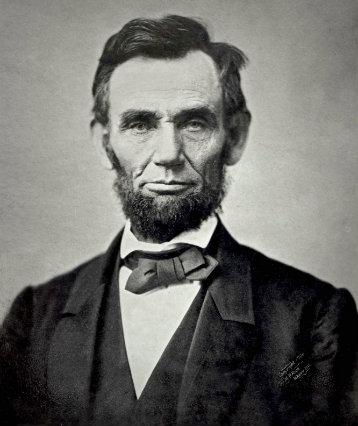

Return to The Meaning of Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday.

Forward the Link

You want to share the page? Add your friend's email below.

Excerpt from the Eulogy of Henry Clay

Introduction

Return to The Meaning of Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday.

Post a Comment