Introduction

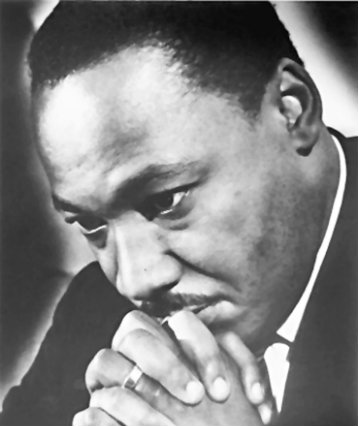

On September 15, 1963, less than three weeks after King delivered his stirring “I Have a Dream” speech before the Lincoln Memorial at the Great March on Washington, four young girls were killed in the bombing of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Three days later, King delivered this eulogy at the funeral service for three of the children—Addie Mae Collins (age 14), Denise McNair, (age 11) and Cynthia Diane Wesley (age 14). A separate service was held for the fourth victim, Carole Robertson (age 14). Along with “The Great March,” this bombing is said to have marked a turning point in the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, garnering much needed support for the passage of the Civil Rights Act the following year. This eulogy shows another aspect of King’s leadership. It also offers another view of the way he links American political and Christian religious ideas.

In his eulogy, King asserts that although the children were “unoffending, innocent, and beautiful . . . victims” they were also “martyred heroines of a holy crusade for freedom and human dignity” who “died nobly.” Can you make sense of this claim? What principles, American or Christian, could make the campaign for civil rights a “holy crusade”? The bombing of the church was known at the time to have been an act of racial terrorism, perpetrated by a group associated with the Ku Klux Klan. Yet King does not blame or rage against the perpetrators, but instead finds fault with, among others, “every minister of the gospel who has remained silent” and “every Negro who has passively accepted the evil system of segregation.” Why does he shift the focus of blame? King then says that these young girls “did not die in vain,” and invites us to think that their “unmerited suffering is redemptive.” What does this mean? In concluding, King offers direct consolation to the bereaved families. Imagining yourself as one among them, would you be consoled by his words?

Post a Comment