Introduction

The true formal declaration of American independence came not on July 4, 1776 but two days earlier, when the Continental Congress voted to approve the following resolution, introduced by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia: “Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved. That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances. That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.” The decision for independence was not a foregone conclusion, and arguments raged with strong support on both sides.

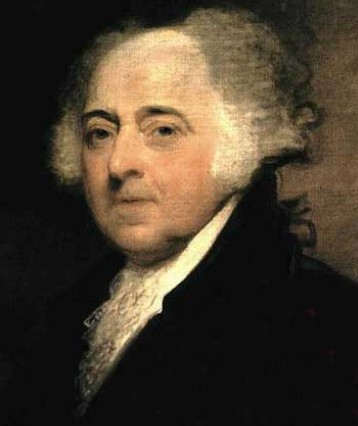

Voting on the Lee resolution, originally proposed on June 7, 1776, was postponed for three weeks, while delegates worked to build support for the measure and sought direction from their home legislatures. This personal account of the final deliberation and vote, written 29 years afterwards by John Adams (1735–1826), makes clear the human drama attending the decision and the role of specific persons in its success, including Adams’ own impassioned pleas for independence.

As latter-day beneficiaries of American independence from Great Britain, we tend to take for granted the wisdom of the decision. Why was the decision so difficult? Can you develop the arguments against independence? Why does Adams say that he regarded the question to be “so simple”? How important was oratory in the result? Is Adams exaggerating when he says that none of the ancient orators of Greece and Rome ever faced a question “of more importance to his country and to the world”? Why, and how, might the question of American independence be important to the world?

Friday, June 28. A new delegation appeared from New Jersey. Mr. William Livingston and all others, who had hitherto resisted independence, were left out. Richard Stockton, Francis Hopkinson, and Dr. John Witherspoon, were new members.

Monday, July 1. A resolution of the Convention of Maryland, passed the 28th of June, was laid before Congress, and read, as follows:

That the instructions given to their deputies in December last, be recalled, and the restrictions therein contained removed; and that their deputies be authorized and empowered to concur with the other United Colonies, or a majority of them, in declaring the United Colonies free and independent States; in forming a compact between them, and in making foreign alliances, &c. . . .

I am not able to recollect whether it was on this or some preceding day, that the greatest and most solemn debate was had on the question of independence. The subject had been in contemplation for more than a year, and frequent discussions had been had concerning it. At one time and another all the arguments for it and against it had been exhausted, and were become familiar. I expected no more would be said in public, but that the question would be put and decided. Mr. Dickinson, however, was determined to bear his testimony against it with more formality. He had prepared himself apparently with great labor and ardent zeal, and in a speech of great length, and with all his eloquence, he combined together all that had before been written in pamphlets and newspapers, and all that had from time to time been said in Congress by himself and others. He conducted the debate not only with great ingenuity and eloquence, but with equal politeness and candor, and was answered in the same spirit.

No member rose to answer him, and after waiting some time, in hopes that some one less obnoxious than myself, who had been all along for a year before, and still was, represented and believed to be the author of all the mischief, would move, I determined to speak.

It has been said, by some of our historians, that I began by an invocation to the god of eloquence. This is a misrepresentation. Nothing so puerile as this fell from me. I began, by saying that this was the first time of my life that I had ever wished for the talents and eloquence of the ancient orators of Greece and Rome, for I was very sure that none of them ever had before him a question of more importance to his country and to the world. They would probably, upon less occasions than this, have begun by solemn invocations to their divinities for assistance; but the question before me appeared so simple, that I had confidence enough in the plain understanding and common sense that had been given me, to believe that I could answer, to the satisfaction of the House, all the arguments which had been produced, notwithstanding the abilities which had been displayed, and the eloquence with which they had been enforced. Mr. Dickinson, some years afterwards, published his speech. I had made no preparation beforehand, and never committed any minutes of mine to writing. But if I had a copy of Mr. Dickinson’s before me, I would now, after nine and twenty years have elapsed, endeavor to recollect mine.

Before the final question was put, the new delegates from New Jersey came in, and Mr. Stockton, Dr. Witherspoon, and Mr. Hopkinson, very respectable characters, expressed a great desire to hear the arguments. All was silence; no one would speak; all eyes were turned upon me. Mr. Edward Rutledge came to me and said, laughing, “Nobody will speak but you upon this subject. You have all the topics so ready, that you must satisfy the gentlemen from New Jersey.” I answered him, laughing, that it had so much the air of exhibiting like an actor or gladiator, for the entertainment of the audience, that I was ashamed to repeat what I had said twenty times before, and I thought nothing new could be advanced by me. The New Jersey gentlemen, however, still insisting on hearing at least a recapitulation of the arguments, and no other gentleman being willing to speak, I summed up the reasons, objections, and answers, in as concise a manner as I could, till at length the Jersey gentlemen said they were fully satisfied and ready for the question, which was then put, and determined in the affirmative.

Return to The Meaning of Independence Day.

Post a Comment