How To Use This Discussion Guide

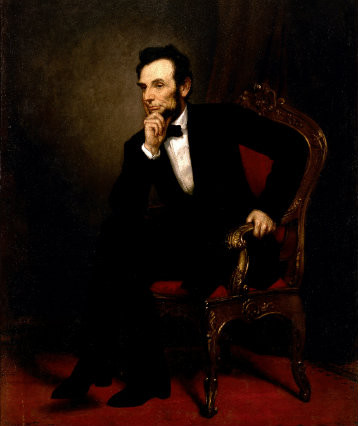

This discussion guide and its related videos were created in conjunction with the AEI Program on American Citizenship, with support from The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation. Materials Included | For this discussion guide, we recommend the following texts from our reader, “Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday”:- Article II, Section 1, Clause 8: Oath of Office

- Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address

- Abraham Lincoln, 1861 Message to Congress in Special Session

- Abraham Lincoln, 1863 letter to New York Democrats

- Abraham Lincoln, Emancipation Proclamation

- Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it;

- Cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text;

- Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development;

- Summarize the key supporting details and ideas;

- Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text;

- Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone; and

- Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning and the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

RH.9-10.1, RH.9-10.2, RH.9-10.3, RH.9-10.5, RH.9-10.8 RH.11-12.1, RH.11-12.2, RH.11-12.4, RH.11-12.8, RH.11-12.9

English Language Arts:RL.9-10.1, RL.9-10.2, RL.9-10.3, RL.9-10.4, RL.9-10.9 RL.11-12.1, RL.11-12.3, RL.11-12.4, RL.11-12.5

Writing Prompts |- What does Lincoln’s example show us about the relationship of executive power to the rule of law? Did Lincoln violate the Constitution or uphold it? Were his actions justified?

- What is the relation of executive power to constitutional government or the rule of law?

- By what standard do we judge when the exercise of executive prerogative is an unjustified violation of the rule of law?

Post a Comment