A. Slavery in the Territories

1. What is “popular sovereignty,” and how does it address the slavery question? What did Douglas hope to achieve by proposing it?

2. Why was Lincoln so opposed to popular sovereignty? Isn’t the rule of the majority at the heart of democracy?

3. According to Lincoln, what’s wrong with (or missing from) Douglas’s account of democracy? How does the principle of popular sovereignty undercut the “sacred right of self-government,” according to Lincoln? How does Lincoln understand free government?

5. In an 1855 letter to his friend Joshua Speed, a Kentucky slaveholder, Lincoln discusses his dislike of slavery and his policy towards it. He says that some people have called him an abolitionist. He says he is not. Why isn’t he an abolitionist? In what ways does his position differ from that of the abolitionists proper?

6. What is Lincoln’s alternative policy toward slavery in the territories?

WATCH: Stephen Douglas’ Defense of Popular Sovereignty

WATCH: Abraham Lincoln, Non-Abolitionist

B. Slavery and the Constitution

1. In the 1857 Dred Scott case, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney declared that “no negro slave ... and no descendant of such slave can ever be a citizen of any state, in the sense of that term as used in the Constitution of the United States.” In his response, Lincoln defends both the Declaration and the Constitution against Taney’s misrepresentations of those documents. How does Lincoln counter these slanders? What is Lincoln’s interpretation of the Declaration?

2. Lincoln believed that the Dred Scott case was wrongly decided. Douglas, on the other hand, expressed his agreement with the decision, and further argued that the Republicans, by questioning the rightness of the decision, were behaving in a revolutionary fashion, undermining the legitimacy of the government. How does Lincoln respond to this charge? Given what Lincoln says about his reverence for the Constitution and the law, is he contradicting his own principles? What is his view of judicial precedent?

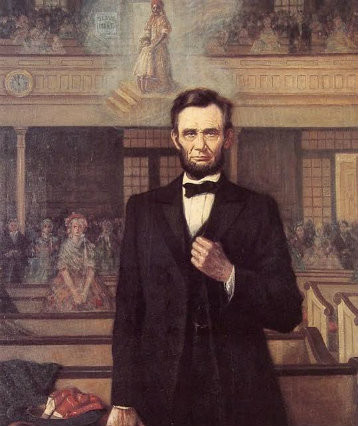

3. In his 1860 Cooper Union Address. Lincoln takes as his text for the speech a single sentence from Douglas which stated that “Our fathers, when they framed the Government under which we live, understood this question [the question of the powers of the federal government respecting slavery in the territories] just as well, and even better, than we do now.” Lincoln agrees with Douglas that the Founding Fathers had the right understanding and he proposes to show what that understanding was. How does Lincoln proceed and what does he accomplish in this speech?

WATCH: Lincoln’s Challenge to Dred Scott

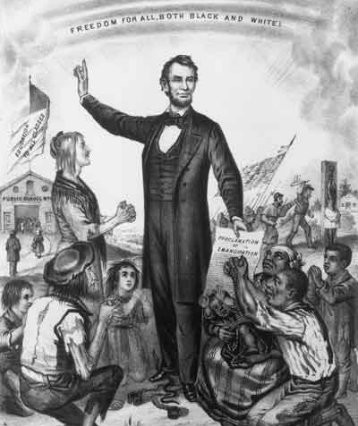

C. Equality and Race

1. Where did Douglas and Lincoln stand on the relationship between races?

2. In the debates, Lincoln argues for the fundamental equality of all men and the right of African Americans to enjoy the fruit of their labor. However, he also declared his opposition to Negro suffrage, and political and social equality in general. As a result, commentators, both then and now, have accused Lincoln of not really believing in the principles of the Declaration. Is Lincoln sincere? Is he consistent?

3. What is the relationship between natural and political rights? With his words, is Lincoln foreclosing the possibility of civil rights for African Americans, or rather is he preparing the ground for later securing those rights?

4. How important was public opinion to Lincoln’s position on civil rights for African Americans? Note in particular what Lincoln says about the role of “universal” feelings in public life in his Peoria Address. Is Lincoln right to take public opinion into account?

WATCH: The Lincoln-Douglas Debates and White Public Opinion

Post a Comment