A. Purpose and Structure of the Speech

1. How did Lincoln come to be in the town of Gettysburg on November 19, 1863, and what role was he expected to play in the events of that day?

2. What is Lincoln’s official purpose? How does he fulfill that purpose in the address?

3. Is Lincoln’s address best described as an elegy (i.e., a funeral oration)? A victory speech marking a great battle won? How does it fit those genres, and how is it different?

4. The Gettysburg Address is a highly abstract speech. There is no mention of Gettysburg, just “a great battle-field.” There is no mention of America or the United States, just “this continent,” or “that nation” and “this nation.” There is no mention of the parties to the conflict, no North or South, no Union or Confederacy, just “a great civil war.” What do you make of the abstract character of the address?

5. Is there a structure to the speech? Why do you think Lincoln has divided the address into three paragraphs?

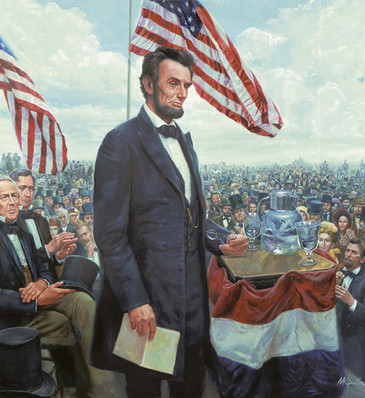

WATCH: The Setting for the Gettysburg Address

B. The First Paragraph

1. Lincoln begins his address with the words “four score and seven years ago.” He could have said “87 years ago” or “in 1776.” Why does he begin his address this way? What sort of language is this, and why might Lincoln have used it?

2. Four score and seven years identifies the birth year as 1776, the year of the Declaration of Independence—not 1787, the year of the Constitution. Why does Lincoln begin with 1776?

3. Who are “our fathers”? Why does Lincoln invoke them?

4. Two features of the new nation are emphasized: liberty and equality. Each is linked to the dominant metaphor of birth. Why does Lincoln use this metaphor to describe the founding of America? Why does he not use plainer terms like “revolution” or “war of independence?”

5. What does it mean to be “conceived in Liberty”? Note that of the handful of common nouns that appear mid-sentence throughout the speech, this is the only one Lincoln capitalized.

6. In the Declaration of Independence, human equality is called a “self-evident truth.” Do you see any significance in the fact that Lincoln refers to equality as a proposition to which the nation is dedicated? How is the Civil War a test of that proposition?

WATCH: Dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal

C. The Second Paragraph

1. In his second paragraph, Lincoln shifts to the present moment, saying “Now we are engaged in a great civil war,” he describes that war as a test. What is being tested?

2. For what purpose has Lincoln’s audience gathered at Gettysburg? What does Lincoln say about that purpose?

WATCH: Conceived in liberty

D. The Third Paragraph

1. At the beginning of the third paragraph, something very strange happens. The turn in the argument is signaled by the word “but.” Resort to “but” always indicates that the speaker is seriously qualifying what he has just said. What is Lincoln retracting in this third and final paragraph or to what is he redirecting the attention of his audience?

2. Why does Lincoln say that “we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground?”

3. Lincoln’s two final sentences, and especially the very long last one, explain what the living ought to do instead of tarrying amidst the graves. They should “rather” (a word he repeats twice)—they should “rather” be “dedicated . . . to the unfinished work” and “the great task remaining.” What does he mean: seeing the war through to victory, or victory plus something more?

3. What was “that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion?” Do you think all of the soldiers who died fighting at Gettysburg were fighting for the same cause? Why or why not?

4. As his very long final sentence unfolds, Lincoln urges his listeners beyond “dedication” to “devotion” and finally “resolve.” What three resolutions does Lincoln ask of his listeners (“that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth”)? What do you make of each of these resolutions?

5. What of the central resolution, the “shall” rather than the “shall not”: “that we here highly resolve . . . that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.” What does this phrase mean? How does it relate to the description of the new nation in the opening paragraph, where the nation was said to have been “conceived in Liberty”?

6. In closing, we shouldn’t overlook the presence of the phrase “under God.” What do you make of the fact that the new birth of freedom is to take place under the superintendence of God?

WATCH: Of the people, by the people, and for the people

Post a Comment