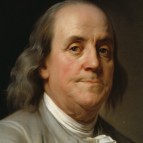

As the youngest son of the youngest son for five generations back, Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) was by custom and tradition destined to be a nobody. Yet thanks to his own resourcefulness, he more than escaped his destiny. Reared in Boston, Franklin struck out on his own at age seventeen to escape traditional and familial authority, arriving in Philadelphia alone and without any visible means of support. By age twenty-four, he had established his own printing business. He soon entered public life and would achieve worldwide fame for his writings and statesmanship, his scientific discoveries and inventions, and his philanthropy—or, as he preferred to call it, his “usefulness” as a citizen. We are indebted to Franklin for many things, including the invention of bifocals, street lamps, the one-arm desk chair, the fireplace damper, and the “Franklin” stove; the founding of the first public library, the first fire insurance company, the University of Pennsylvania, and the American Philosophical Society; and his vast service to our new nation, as delegate, counselor, author, and diplomat.